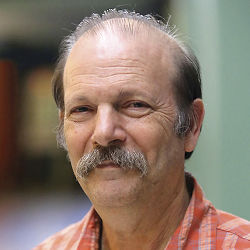

Moshe Vardi's horizons are big when it comes to computer science. Celebrated for his contributions to formal methods and computational complexity, he is also well known for his role with ACM, and, in particular, with this publication. Vardi took over as Editor-in-Chief of Communications of the ACM in 2008. Though he stepped down to become a Senior Editor in 2017, he continues to publish regularly on topics from corporate ethics to post-graduate education. Here, he talks about socioeconomics, social media, and the impact of computing on society.

You have spent your career focusing on automated reasoning and logic, but in recent years, it seems like you have been just as active in examining the social implications of technology.

I think we need to learn a bit from the Amish. People think the Amish are anti-technology, but that's not a nuanced view. The Amish are not anti-technology, they just have a set of values they want to live by. And when a new technology comes in, the council of elders evaluates it and says, "What will be the impact?" I have come to the conclusion that we need to do the same in computing.

That's not a question most technologists are asking themselves.

How is technology affecting society? It's a very fundamental question, and we do not think much about it. We are technologists. We enjoy technology, and we get excited by technical challenges. It's not clear that we can do like the Amish, but we can stop and ask ourselves, "What will be the impact?"

For example, the Amish believe in living in tight communities. With a horse and buggy, you can't go too far, but with an automobile, you are going to go farther. So, the automobile is out. With a cellphone, people are going to talk to each other. That's a good thing. So, they have cellphones, but no smartphones and no social media.

Social media is one of the more prominent examples of a technology that has impacted society in complex and not uniformly positive ways.

One of our failures is not to assess what actually happens when you apply things on a large scale. At Facebook, the mantra for many years was frictionless sharing. What happens when two and a half billion people can share things very easily? It's convenient, but it opens the door to all kinds of other negative phenomena.

Those negative phenomena did not get much attention until after social media use was well entrenched.

In the past 50 years, we created a race against the machine—to quote Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee (https://stanford.io/3Q7YM3F)—and ushered in the so-called knowledge economy. And for us, in the ACM community, we are loving it, because we are the winners of this revolution.

Who are the losers? The data shows working-class people in the U.S. have lost ground in the last generation. This is what economists call labor polarization. The high-skill jobs have done well; in fact, there are many more jobs that require high-skilled workers than there used to be. Meanwhile, low-skilled workers are getting minimum wage, which has not changed in 50 years, and the middle-skill part of the labor market has shrunk. That created a socioeconomically polarized society, and into this polarized society, we threw the gasoline of social media.

AI is another area where development seems to move faster than society can keep up with.

Deep learning has been a dramatic success, and now we need to ask ourself the question Stuart Russell has posed: "What if we succeed?" (https://bit.ly/3BNTsOw). Suppose we can develop Artificial General Intelligence. What happens then?

It's a question that, amazingly, very few people have asked. If you go back to Turing's original 1950 paper, it is incredibly prophetic on the possibility of machine intelligence. Yet while Turing is very excited about the technical challenges, the paper is completely devoid from thinking through the implications. Erik Brynjolfsson refers to the so-called Turing Test as the Turing Trap (https://stanford.io/3JAXbkt), because if we are trying to imitate humans, we could just end up reproducing all of our faults.

Are there places inside the discipline where you have seen progress in terms of our willingness to engage with these sorts of questions?

As a discipline, we have not looked at what our work is doing to society, and we're still having an incredibly hard time coming to terms with it. In fact, I remember when I started talking about automation and its adverse impact on labor. Somebody came up to me after the talk—I don't remember who—and said, "Don't give talks like this. It's going be bad for funding."

"Suppose we can develop Artificial General Intelligence. What happens then?"

But the industry is successful, and it's not so simple to say, "No, I want nothing to do with Silicon Valley." Many of my students go there. Many academics get funded by them. ACM is embedded with these companies. The conversation about social responsibility is difficult to have. And sometimes, the way people respond to difficult conversations is to say, "Let's not have them. It's too unpleasant."

What do you tell your students?

Many of my undergraduate students aspire to go to Silicon Valley, where their starting salaries with a B.S. degree are probably more than people get as an assistant professor with a Ph.D. They don't want go to graduate school; they want to go into the industry and do well.

So I've been involved, at Rice, in designing a course about the ethics of technology. In this course, there's no final exam. Instead, students have to write an essay about their personal response toward professional social responsibility. It can be very moving to read these essays. Some students almost seem to say, "I was blind, and now I can see. I thought that technology was an unmitigated positive, and now I see that it's more complicated."

It sounds like a pretty great public service if you can help students break out of the binary, "right vs. wrong" thinking that's dogged the debate about issues from public health to politics.

It's easy to say that an issue like this is all black or all white. It's not. Of course, technology has been a huge positive. I mean, we can have this conversation on Zoom and I can finally see what you look like. And throughout the pandemic, most knowledge workers were able to go home and keep working, and the economy did not collapse.

But, you know, that comes at a price. If you're an educated professional, you live in a bubble, and you interact mostly with other educated professionals. Your interactions outside that bubble are often transactional, and you know very little about people's lives. If I order something from Amazon, somebody comes and delivers it to my house. If I'm home, I might thank them for the delivery, but I wouldn't ask them to come in and have a cup of coffee. Maybe I should.

Your name has come to be very closely linked to this publication, thanks to your long tenure as Editor-in-Chief and the work you oversaw in the early 2000s refreshing its tone and broadening its perspective. How did you first get involved?

I got to know John White, who was the CEO of ACM for many years, when I was a member of the CRA board. This was back around 2004, during the so-called Image Crisis, which followed the dot-com crash, when people were worried about offshoring and the future of the discipline. As you may have noticed, I have opinions, and I'm not shy about voicing them. So, John approached me and said, "We need to understand exactly what's going on." I agreed. And he said, "Well, if you think it's important, would you be willing to co-sponsor a study about the impact of offshoring on the computing profession?"

We issued that report in 2006, and it made quite an impact. And I guess no good deed goes unpunished, because John then asked me to take over as Editor-in-Chief of Communications. He executed the request perfectly, in an ambush with Dave Patterson and Maria Klawe. Then one thing led to another, and we began to realign the publication around a bigger picture of computing today, including computing and society.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment