The field of artificial intelligence (AI) was founded at a conference at Dartmouth College in 1956, with John McCarthy as one of its influential attendees. McCarthy subsequently expanded on the notion of logical AI, writing what appears to be the first paper on the topic, “Programs With Common Sense,” in 1958.

In the paper, he laid out for the first time the specifics of how a program might “know” things and reason with them, according to Stuart Russell, professor of computer science at the University of California, Berkeley. “McCarthy developed what he considered to be the right way to build intelligent systems,” says Russell.

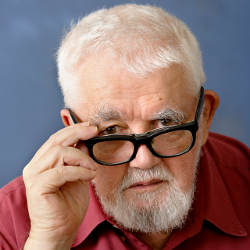

McCarthy passed away on Oct. 23 in Stanford, CA, at 84, and had served on the Stanford faculty for four decades.

He received the A.M. Turing Award in 1971 for his work in AI, the Kyoto Prize in 1988, and the U.S. National Medal of Science in 1991.

While he was most celebrated for his AI work (including coining the term “artificial intelligence”) and for creating the Lisp programming language, he was also one of the first to investigate how to rigorously prove properties of programs. He invented abstract syntax; created the nonmonotonic logic technique called circumscription; and invented the garbage collector. He also made original contributions to ideas for space travel, including what he called the “space fountain,” “a kind of space elevator,” says Pat Hayes, once McCarthy’s research assistant and now senior research scientist at the Institute for Human and Machine Cognition in Pensacola, FL.

“His students included pioneers in logic programming, AI planning, several branches of theoretical computer science, robotics, machine learning, formal ontologies, knowledge representation, cognitive science, formal philosophy, and much more,” says Hayes. “John was Descartes reincarnated in the 21st century, but with a better sense of humor.”

Indeed, in his 2001 short story, “The Robot and the Baby,” McCarthy cleverly explores the question of whether robots should have emotions.

McCarthy was “a very, very clear thinker regardless of the topic—politics, sociology, the water supply in the San Andreas Basin, anything,” recalls Hayes. “When you brought up a subject, you knew right away he’d already done the math and worked out the numbers. And if he found someone who was more knowledgeable than he on a subject, he’d take them aside, buy them a drink, and start grilling them. He was like a human vacuum cleaner for information from experts.”

McCarthy was in the habit of posting many of his thoughts on the Web.

“Essentially, they were a long list of his thesis ideas that were free for the taking,” says Russell. “He also created a Q&A page with a collection of questions he’d been asked over and over again over the years…along with the correct answers so that he didn’t have to be bothered answering them one more time.”

Another of McCarthy’s important contributions to computing involved time sharing. Although not the first to conceive the idea, his was the first project to implement a time-sharing system at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1957 on a modified IBM 704 computer.

“For John, it was just a necessary solution to a nuisance,” explains Russell. “MIT only had a limited number of computers and many people who wanted to use them. He believed time sharing would be a good solution and so he made it happen. And you can read about it in his ‘Reminiscences on the History of Time Sharing.’ I’m sure he thought he’d made just a minor contribution, but for computer science as a whole, it was one of the major ideas for computer systems.”

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment