Fumbling the Future: How Xerox Invented, Then Ignored, the First Personal Computer is the title of a classic 1998 book by D.K. Smith and R.C. Alexander that tells the gripping story of how Xerox invented the personal-computing technology in the 1970s, and then "miscalculated and mishandled" the opportunity to fully exploit it. To "fumble the future" has since become a standard phrase in discussions of advanced technology and its commercialization.

Another example definitely worth watching is a recently discovered copy of a 1993 AT&T commercial (http://www.geekosystem.com/1993-att-video/), with a rather clear vision of the future, predicting what was then revolutionary technology, such as paying tolls without stopping and reading books on computers. As we know today, the future did not work out too well for AT&T; following the telecom crash of the early 2000s, the telecom giant had to sell itself in 2005 to its former spin-off, SBC Communications, which then took the name AT&T.

This editorial is a story of how I fumbled the future. It is not widely known, but I almost invented the World-Wide Web—twice (smiley face here).

In 1988 I was a research staff member at the IBM Almaden Research Center. In response to a concern that IBM was not innovative enough, a group of about 20 researchers, including me, from different IBM Research labs, was tasked with envisioning an exciting information-technology-enabled 21st-century future. The "CS Future Work Group" met several times over a period of 18 months and produced a "vision" titled "Global Multi-Media Information Utilities." What did this somewhat clunky name refer to? To quote: "The utility is assumed to have a geographical coverage similar to that of today’s telephone system, over which it can deliver, on a flexible pay-as-you-go basis, the most varied multimedia information services, such as multimedia electronic messaging, broadcasting, multimedia reference and encyclopedia database querying, rich information services, teleconferences, online simulation, visualization, and exploration services." In other words, while we did not predict Google, Facebook, or Wikipedia, we did describe, rather presciently I think, the World-Wide Web.

What happened with that exciting vision? Very little, I am afraid. Our report was issued as an IBM Research Report. It was deemed significant enough to be classified as "IBM Confidential," which ensured that it was not widely read, and it had no visibility outside IBM. The publication of the report practically coincided with the start of IBM’s significant business difficulties in the early 1990s, and the corporation’s focus naturally shifted to its near-term future. In other words, we fumbled the future. (At my request, the report was recently declassified; see https://researcher.ibm.com/researcher/files/zurich-pj/vision1%20-%202010.pdf.)

The future looks clear only in hindsight. It is rather easy to practically stare at it and not see it.

In the early 1990s, the computing environment at IBM Research was shifting from mainframe-based to workstation-based. Users requested an interface that would integrate the two environments. I got involved, together with several other people, in the development of ARCWorld, a software tool with a graphical user interface that allowed a user to manage and manipulate files on multiple Internet-connected computer systems. Our focus was on file manipulation, rather than information display, but ARCWorld could have been described as a "file browser." It was clear to all involved that ARCWorld was an innovative approach to wide-area information management, but it was difficult to see how it could fit within IBM’s product strategy at the time. Some feeble attempts at commercialization were not successful. We fumbled the future, again.

What is the moral of these reminiscences? My main lesson is that fumbling the future is very easy. I have done it myself! The future looks clear only in hindsight. It is rather easy to practically stare at it and not see it. It follows that those who did make the future happen deserve double and triple credit. They not only saw the future, but also trusted their vision to follow through, and translated vision to execution. We should all recognize the incredible contributions of those who did not fumble the future.

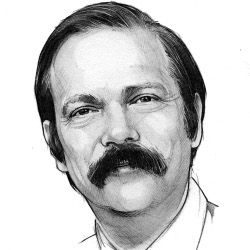

Moshe Y. Vardi, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment