Sustainability is undeniably a grand challenge. As the world population and the average affluence per person continues to grow, we are eagerly consuming Earth’s natural resources. The Earth Overshoot Day marks the date when the demand for ecological resources by humankind in a given year exceeds what the Earth can regenerate in a year’s time. While the world’s Earth Overshoot Day fell at the end of December in the early 1970s, it has progressively antedated since then and was computed to fall on Aug. 1 in 2024. The overshoot day is (much) earlier for many countries, as early as Feb. 26 for Singapore, March 13 for the U.S., March 26 for Canada, and April-May for most European countries as well as South Korea, Israel, Japan, and China.a

The continuously growing consumption of Earth’s resources, including materials and energy sources, (inevitably) induces climate change. Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions result in detrimental global warming, and a recent study reports that the contribution of information and communication technology (ICT) to the world’s global GHG emissions, currently between 2.1% and 3.9%,11 is growing at rapid pace. While this percentage may seem small, it is not. In fact, ICT’s contribution to global warming is on par with (or even larger than) the aviation industry, which is estimated to be around 2.5%.b

Key Insights

Computing is responsible for a significant and growing fraction of the world’s global carbon footprint.

The status quo in which we keep per-device carbon footprint constant would lead to a 5.4× sustainability gap for computing relative to the Paris agreement within a decade

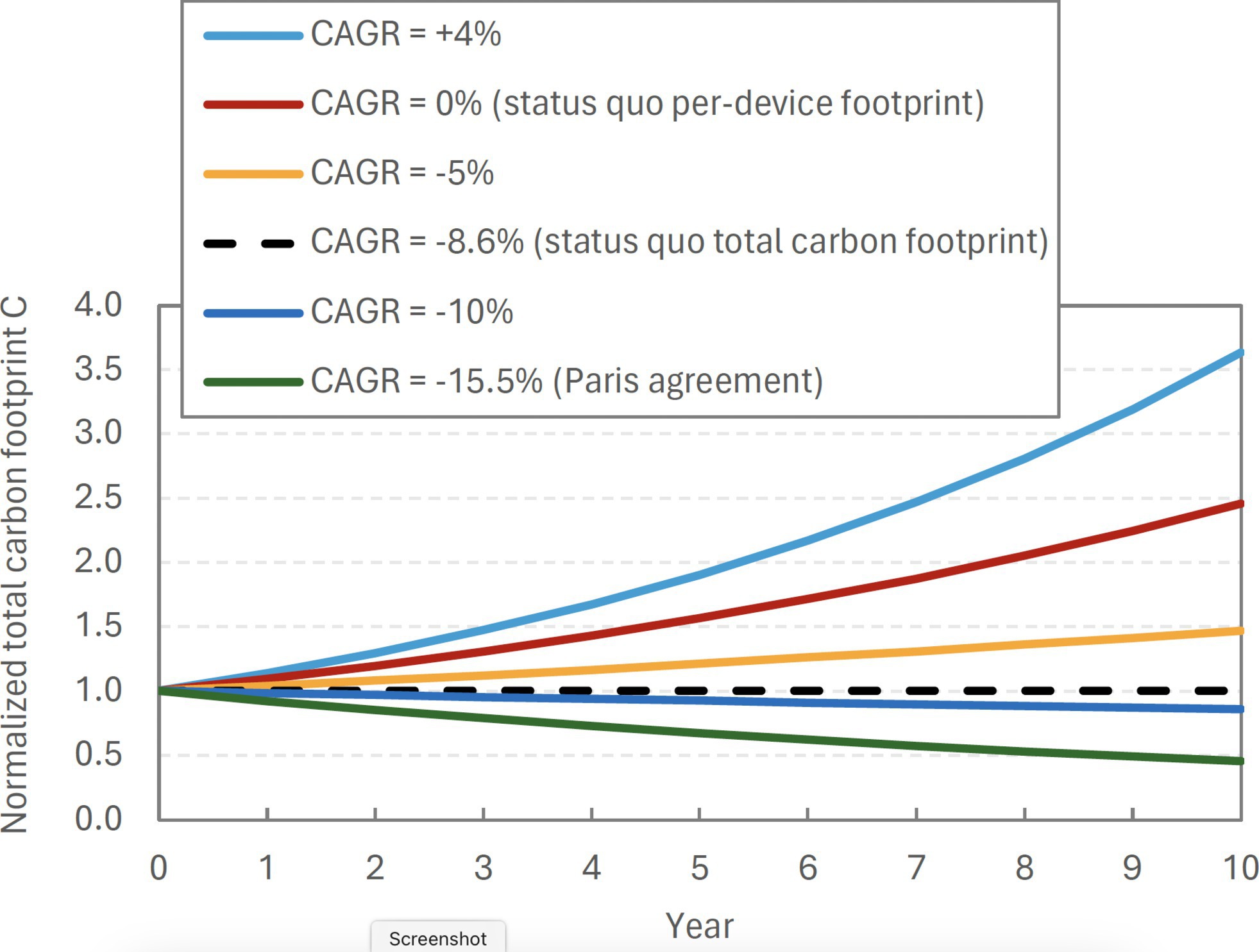

Meeting the Paris agreement for computing requires reducing the per-device carbon footprint by 15.5% per year under current population and affluence growth curves.

Based on a select number of published carbon footprint reports, it appears that while vendors indeed reduce the per-device carbon footprint, it does not seem to be enough to close the gap, urging our community to do more.

To combat global warming, the Paris Agreement under the auspices of the United Nations (UN) aims to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius, and preferably to 1.5 degrees Celsius, compared to pre-industrial levels. In 2019, the UN stated that global emissions must be cut by 7.6% each year over the next decade to meet the Paris Agreement.c More recently in November 2023, the UN stated that insufficient progress has been made so far to combat climate change.d

Given the pressing need to act, along with the significant and growing contribution of computer systems to global warming, it is imperative that we, computer system engineers, ask ourselves what we can do to reduce computing’s environmental footprint within the socio-economic context. To do so, this article reformulates the well-known and widely used IPAT model,6 such that we can reason about the three contributing factors: population growth, increased affluence or number of computing devices per person, and carbon footprint per device over its entire lifetime, which includes the so-called embodied footprint for manufacturing, assembly, transportation, and end-of-life processing, and the operational footprint due to device usage during its lifetime.13

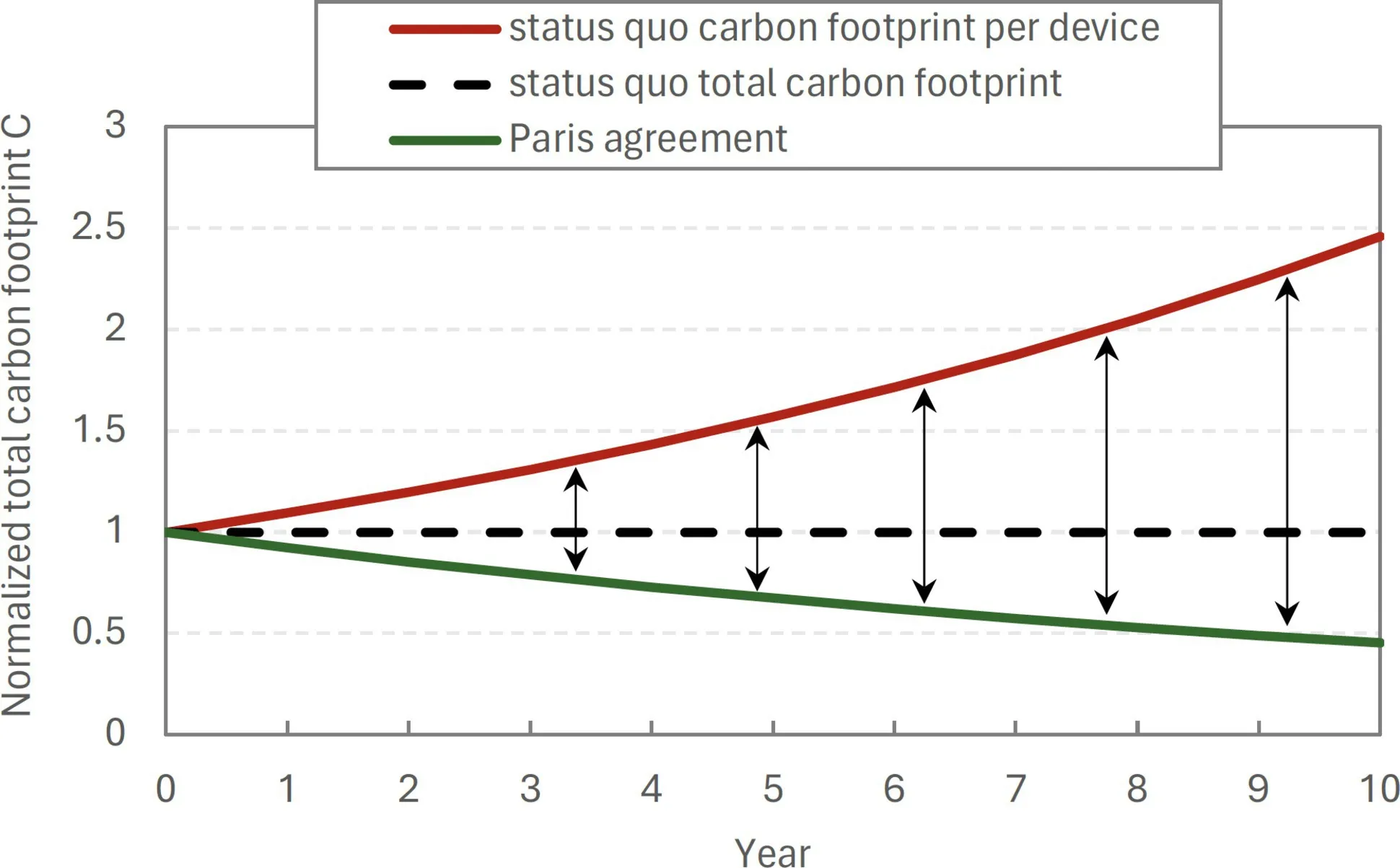

The growth in population and affluence leads to a growing sustainability gap as illustrated in Figure 1. If we were to keep the carbon footprint per device constant relative to the present time, the total carbon footprint due to ICT would still increase by 9.4% per year, leading to a 2.45× increase in GHG emissions over a decade. In contrast, meeting the Paris Agreement requires that we reduce GHG emissions by a factor 2.2×. Bridging this widening sustainability gap between the per-device status quo and the Paris Agreement requires that we reduce the carbon footprint per device by 15.5% per year or by a cumulative factor of 5.4× over a decade.

Analyzing the carbon footprint for a select number of computing devices (smartwatches, smartphones, laptops, desktops, and servers) reveals that vendors do pay attention to sustainability. Indeed, the carbon footprint per computing device tends to reduce in recent years, at least for some devices by some vendors. However, the reduction in per-device carbon footprint achieved in recent years appears to be insufficient to close the sustainability gap. The overall conclusion is that a concerted effort is needed to significantly reduce the demand for computing devices while reducing the carbon footprint per device at a sustained rate for the foreseeable future.

The IPAT Model

IPAT is the acronym of the well-known and widely used equation6 which quantifies the impact I of human activity on the environment:

(1)P stands for population (that is, the number of people on earth), A accounts for the affluence per person or the average consumption per person, and T quantifies the impact of the technology on the environment per unit of consumption. The impact on the environment can be measured along a number of dimensions, including the natural resources and materials used (some of which may be critical and scarce); GHG emissions during the production, use, and transportation of products; pollution of ecosystems and its impact on biodiversity; and so on. The IPAT equation is used as a basis by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change (IPCC) in their annual reports.

The IPAT equation has been criticized as being too simplistic, assuming that the different variables in the equation are independent of each other. Indeed, in contrast to what the above formula may suggest, improving one of the variables does not necessarily lead to a corresponding reduction in overall impact. For example, reducing T in the IPAT model by 50% through technology innovations to reduce the environmental impact per product does not necessarily reduce the overall environmental impact I by 50%. The fundamental reason is that a technological efficiency improvement may lead to an increase in demand and/or use, which in turn may lead to an increase, rather than a reduction, in overall impact. This is the well-known rebound effect or Jevons’ paradox, named after the English economist Williams Stanley Jevons, who was the first to describe this rebound effect. He observed that improving the coal efficiency of the steam engine led to an overall increase in coal consumption.2 Although there is no substantial carbon tax as of today, Jevons’ paradox still (indirectly) applies to computer systems. Efficiency gains increase a computing device’s compute capabilities, which stimulates its deployment (that is, more devices are deployed due to increase in demand) and its usage (that is, the device is used more intensively). The result may be a net increase in total carbon footprint across all devices despite the per-device efficiency gains.

The rebound effect can be (partly) accounted for in the IPAT model by expressing each of the variables as a compound annual growth rate (CAGR), defined as follows:

(2)with V0 the variable’s value at year 0 and Vt its value at year t. The IPAT model can be expressed using CAGRs for the respective variables:

(3)This formulation allows for computing the annual growth rate in overall environmental impact or GHG emissions as a function of the growth rates of the individual contributing factors. If the growth rates incorporate the rebound effect, that is, higher consumption rate as a result of higher technological efficiency, the model can make an educated guess about the expected growth rate in environmental impact.3

The Environmental Impact of Computing

We now reformulate the IPAT equation such that it provides insight for computer system engineers to reason about the environmental impact of computing within its socio-economic context. We do so while focusing on GHG emissions encompassing the whole lifecycle of computing devices. The total GHG emissions C incurred by all computing devices on earth can be expressed as follows:

(4)P is the world’s global population. D/P is a measure for affluence and quantifies the number of computing devices per capita on earth. C/D is a measure for technology and corresponds to the total carbon footprint per device. Note that C/D includes the whole lifecycle of a computing device, from raw material extraction to manufacturing, assembly, transportation, usage, and end-of-life processing. We now discuss how the different factors P, D/P, and C/D in the above equation scale over time.

Population. The world population P has grown from one billion in 1800 to eight billion in 2022. The UN expects it to reach 9.7 billion in 2050 and possibly reach its peak at nearly 10.4 billion in the mid 2080s.e The world population annual growth rate was largest around 1963 with a CAGRP = +2.1%. Since then, the growth rate has reduced to around CAGRP = +0.9% according to the World Bank.f

Affluence. The number of devices per person D/P increases at a fairly sharp rate7 (see Table 1). On average across the globe, the number of connected devices per capita increased from 2.4 in 2018 to 3.6 in 2023, or CAGRD/P = +8.4%. In the western world, that is, North America and Western Europe, the number of devices per person is not only a factor 2× to 4× larger than the world average, it also increases much faster with a CAGRD/P above +10%. The increase in the number of devices is in line with the annual increase in integrated circuits (ICs), that is, estimated CAGR = +10.2% according to the 2022 McClean report from IC Insights.18

| Region | 2018 | 2023 | CAGR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global | 2.4 | 3.6 | +8.4% |

| Asia Pacific | 2.1 | 3.1 | +8.1% |

| Central and Eastern Europe | 2.5 | 4.0 | +9.9% |

| Latin America | 2.2 | 3.1 | +7.1% |

| Middle East and Africa | 1.1 | 1.5 | +6.4% |

| North America | 8.2 | 13.4 | +10.3% |

| Western Europe | 5.6 | 9.4 | +10.9% |

Technology. The carbon footprint per device C/D and its scaling trend CAGRC/D is much harder to quantify because of inherent data uncertainty and the myriad computing devices. The carbon footprint of a device depends on many factors, including the materials used, how those materials are extracted, how the various components of a device are manufactured and assembled, how energy efficient the device is, where these devices are used, the lifetime of the device, how much transportation is involved, how end-of-life processing is handled, and so on. Despite the large degree of uncertainty, it is instructive and useful to analyze lifecycle assessment (LCA) or product carbon footprint (PCF) reports that quantify the environmental footprint of a device. All LCA and PCF reports acknowledge the degree of data uncertainty; nevertheless, they provide invaluable information for consumers to assess the environmental footprint of devices.

To understand per-device carbon footprint scaling trends, we now consider a number of computing devices from different vendors. We leverage the carbon footprint numbers published in the products’ respective LCA or PCF reports. In particular, we use the resources available from Apple,g Google,h and Dell.i We now discuss carbon footprint scaling trends for smartwatches, smartphones, laptops, desktops, and servers.

The bottom line is that per-device carbon footprint has not increased dramatically over the past years and has even significantly decreased in some cases. Several interesting conclusions can be reached upon closer inspection across devices and vendors.

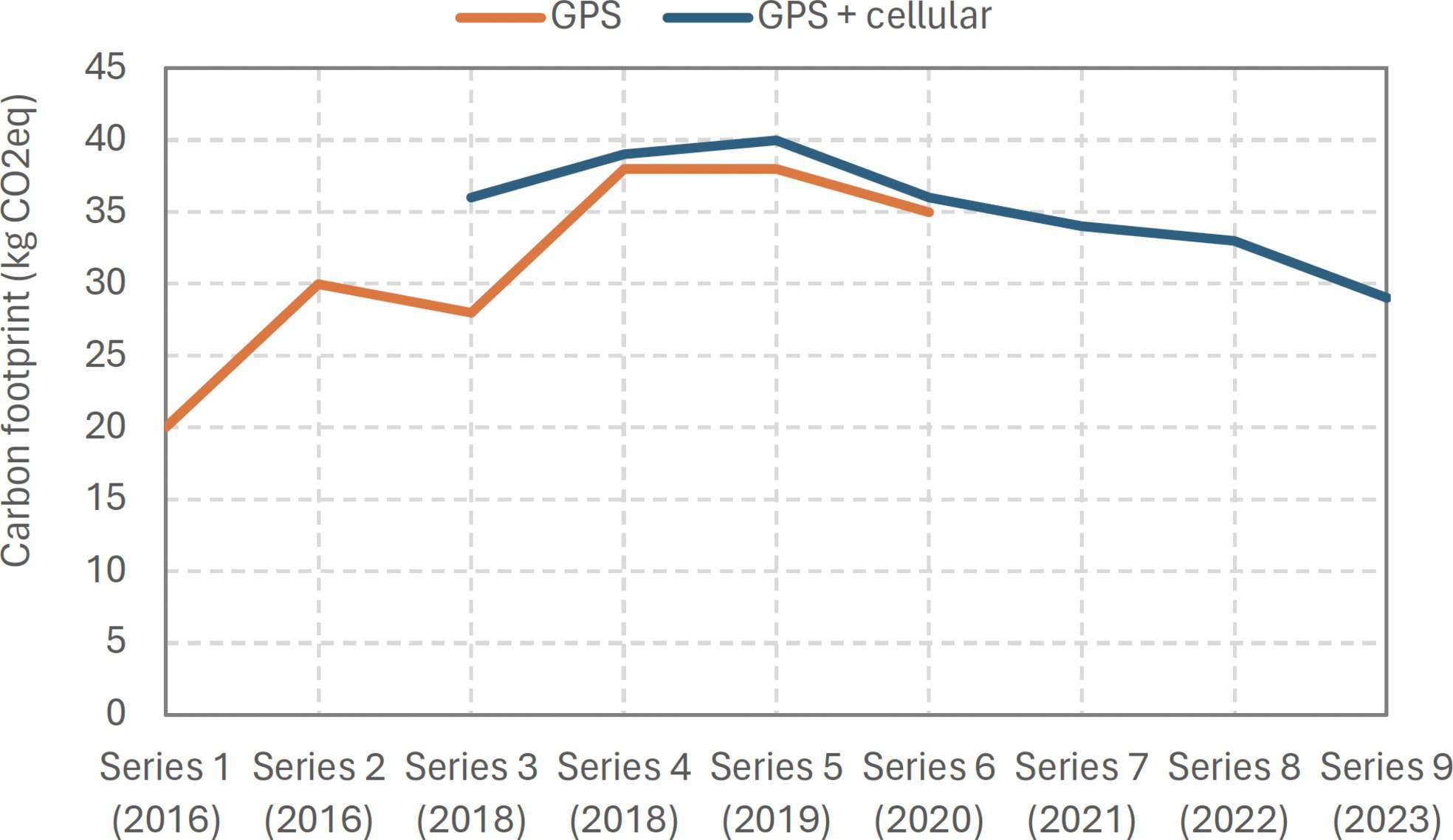

Smartwatches. Figure 2 quantifies the carbon footprint for different generations of Apple Watches with similar capabilities (GPS versus GPS plus cellular) and sport band. All watches feature either an aluminum case (42mm in Series 1 to 3, 44mm in Series 4 to 6, and 45mm in Series 7 and 8) or a stainless case (Series 9). It is surprising perhaps to note that a smartwatch’s carbon footprint was on a rising trend until 2019 before declining. Indeed, the carbon footprint of a GPS watch has increased with a CAGRC/D = +23.9% from 2016 (Series 1) until 2019 (Series 5), while the carbon footprint of a GPS-plus-cellular watch has decreased with a CAGRC/D = −7.7% from 2019 (Series 5) until 2023 (Series 9).

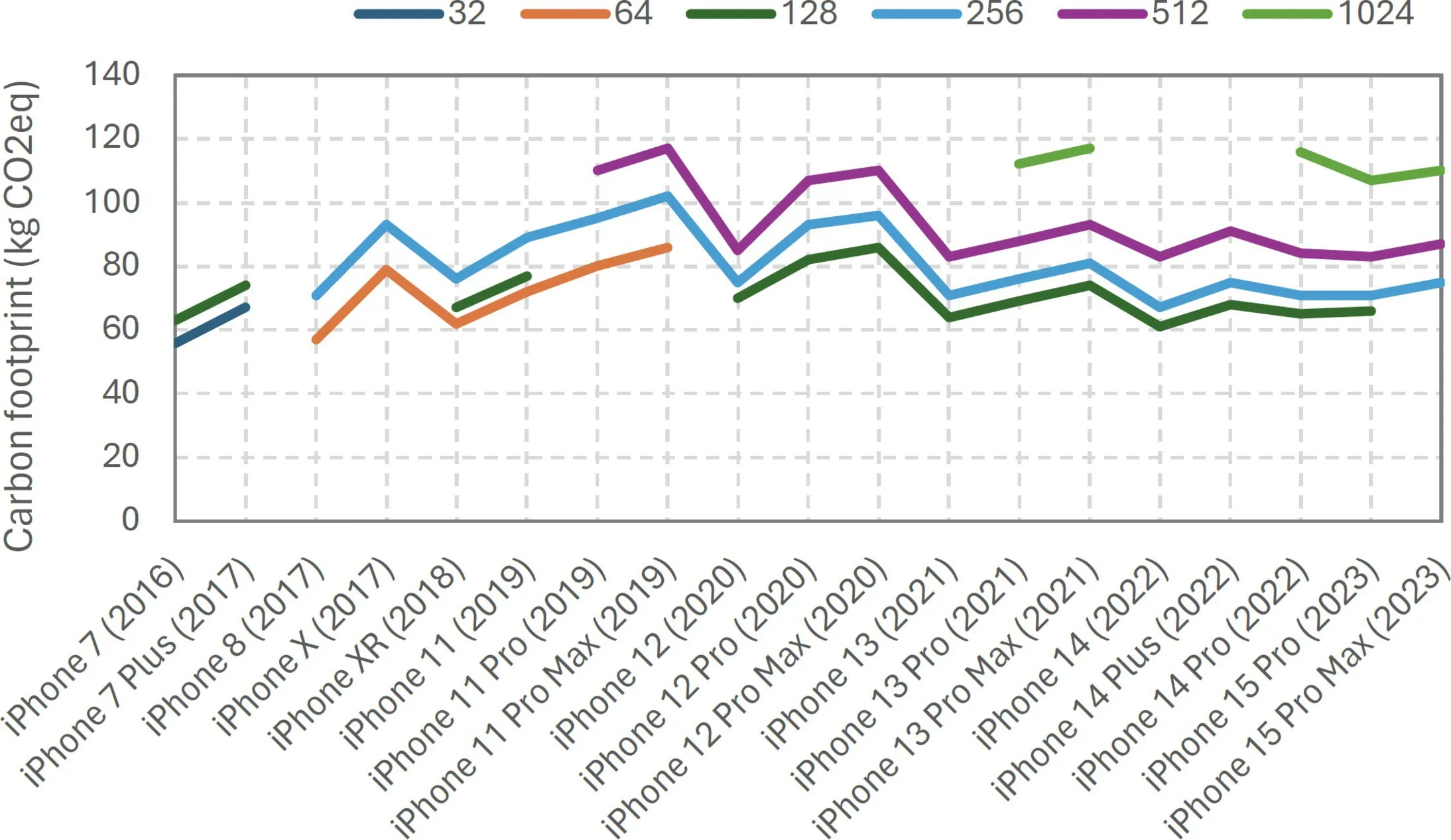

Smartphones. Figure 3 illustrates the carbon footprint for Apple iPhones starting with iPhone 7 (release date in 2016) until iPhone 15 Pro Max (release date in 2023) with different SSD capacity. We note a similar trend for the Apple smartphones as for the smartwatches: Per-device carbon footprint increased until 2019, when it began declining. Indeed, from iPhone 8 (2017) to iPhone 11 Pro Max (2019) with 256GB SDD, the carbon footprint has increased from 71kg to 102kg CO2eq (CAGRC/D = +19.8%). From 2019 onward, we note a decrease in carbon footprint per device: From iPhone 11 Pro Max (2019) to iPhone 15 Pro Max (2023) with 512GB SDD, the carbon footprint decreased from 117kg to 87kg CO2eq (CAGRC/D = −7.1%). While Apple has been steadily decreasing the smartphone carbon footprint since 2019, it is worth noting that the declining trend is slowing down in recent years. For example, from iPhone 13 Pro Max (2021) to iPhone 15 Pro Max (2023) with 512GB SSD, the carbon footprint has decreased from 93kg to 87kg CO2eq (CAGRC/D = −3.3%).

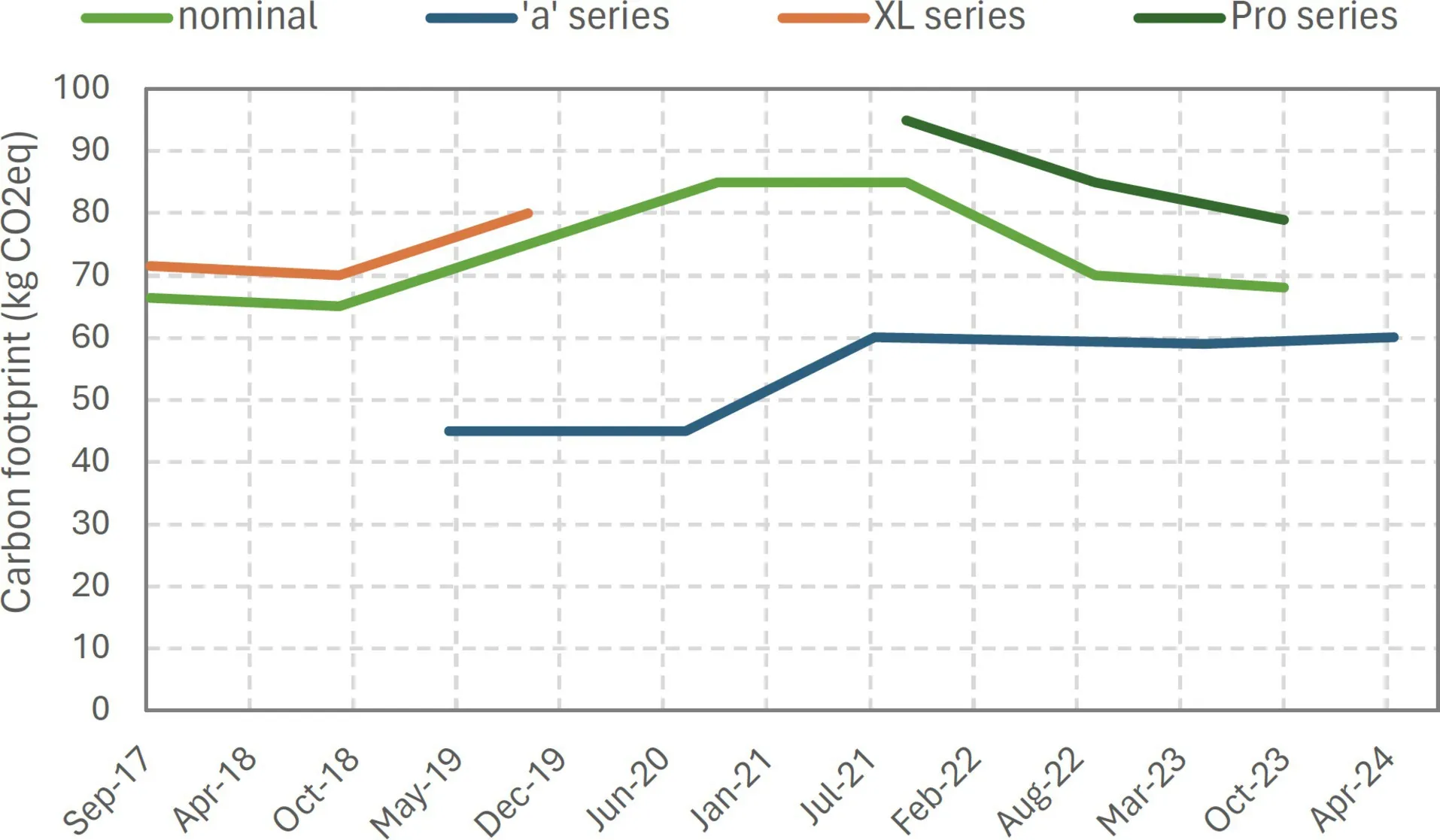

To analyze these trends across vendors, Figure 4 reports results for the Google Pixel phones; the plot reports carbon footprints for the nominal series (Pixel 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8), the ‘a’ series (Pixel 3a, 4a, 5a, 7a, 8a), the XL series (Pixel 2XL, 3XL, 4XL), and the Pro series (Pixel 6Pro, 7Pro, 8Pro). As for Apple, we note a declining trend in recent years for Google smartphones: The per-device carbon footprint increased until mid 2021, after which it started trending downward. This is noticeable for the nominal series as well as for the high-end phone series (XL and Pro series). The decrease in carbon footprint since 2021 is substantial for the nominal series (CAGRC/D = −10.5%) and the Pro series (CAGRC/D = −8.8%), while remaining invariant for the ‘a’ series since mid 2021.

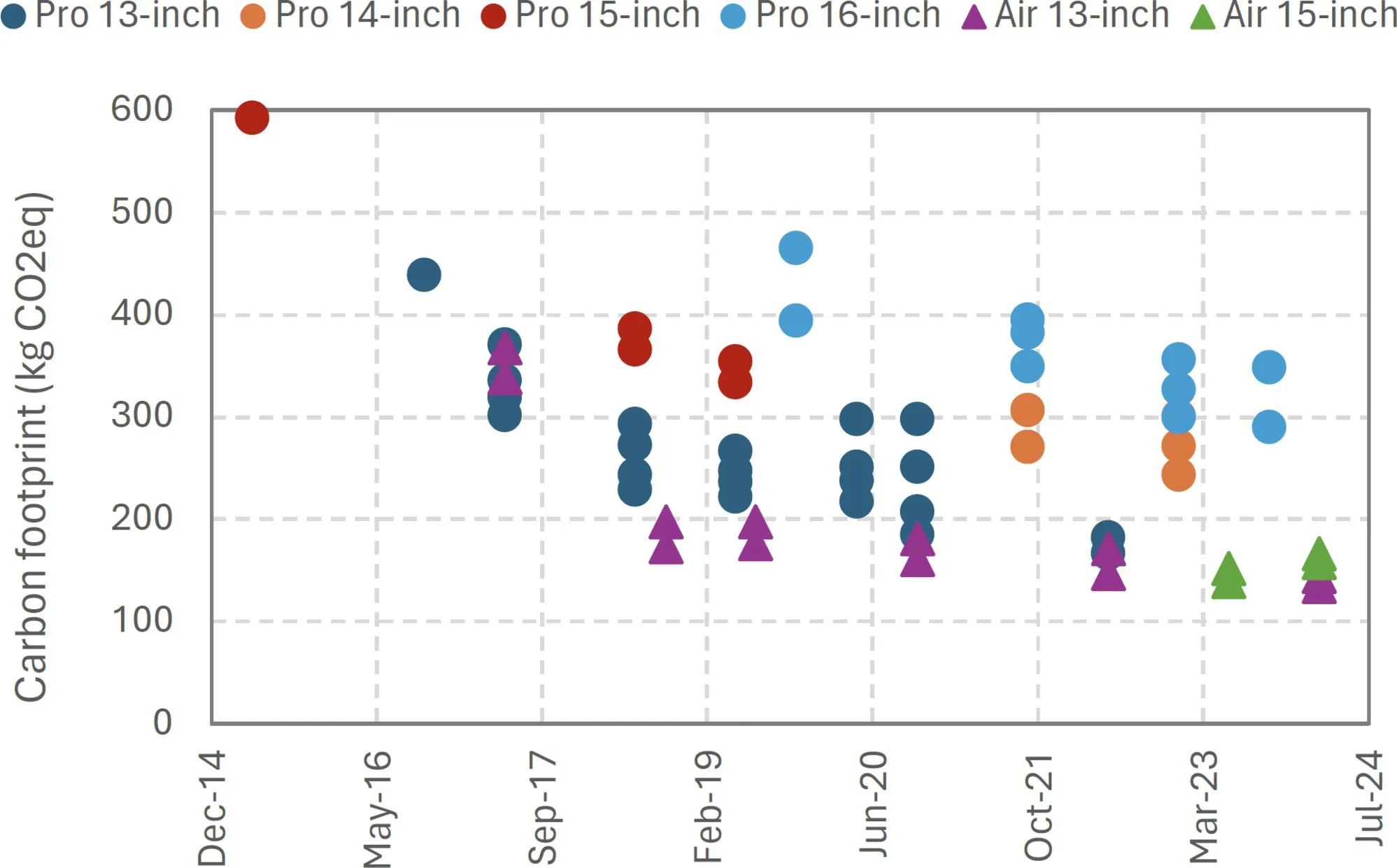

Laptops. Figure 5 reports the carbon footprint for Apple MacBook Pro and MacBook Air laptops with different configurations (screen size, see legend) as a function of their respective release dates; multiple laptops are reported per release date with different storage capacity, core count, and frequency. Several observations are worth noting. First, and perhaps not surprisingly, MacBook Air laptops incur a smaller carbon footprint than the more powerful MacBook Pro laptops. Second, for a given screen size, we note a steady decrease in carbon footprint, for example, MacBook Pro 16-in. (CAGRC/D = −6.9% from 2019 to 2023) and MacBook Air 13-in. (CAGRC/D = −5.1% from 2018 to 2024). Third, while this continuous decrease in per-device carbon footprint is encouraging, there is a caveat: Discontinuing a particular laptop configuration and replacing it with a more powerful device comes with a substantial carbon footprint increase. In particular, replacing the MacBook Pro 15-in. with a 16-in. configuration mid-2019 increases the carbon footprint by at least 11.3%; likewise, the transition from 13-in. to 14-in. in the second half of 2022 led to an increase of at least 33.5% for entry-level MacBook Pro laptops.

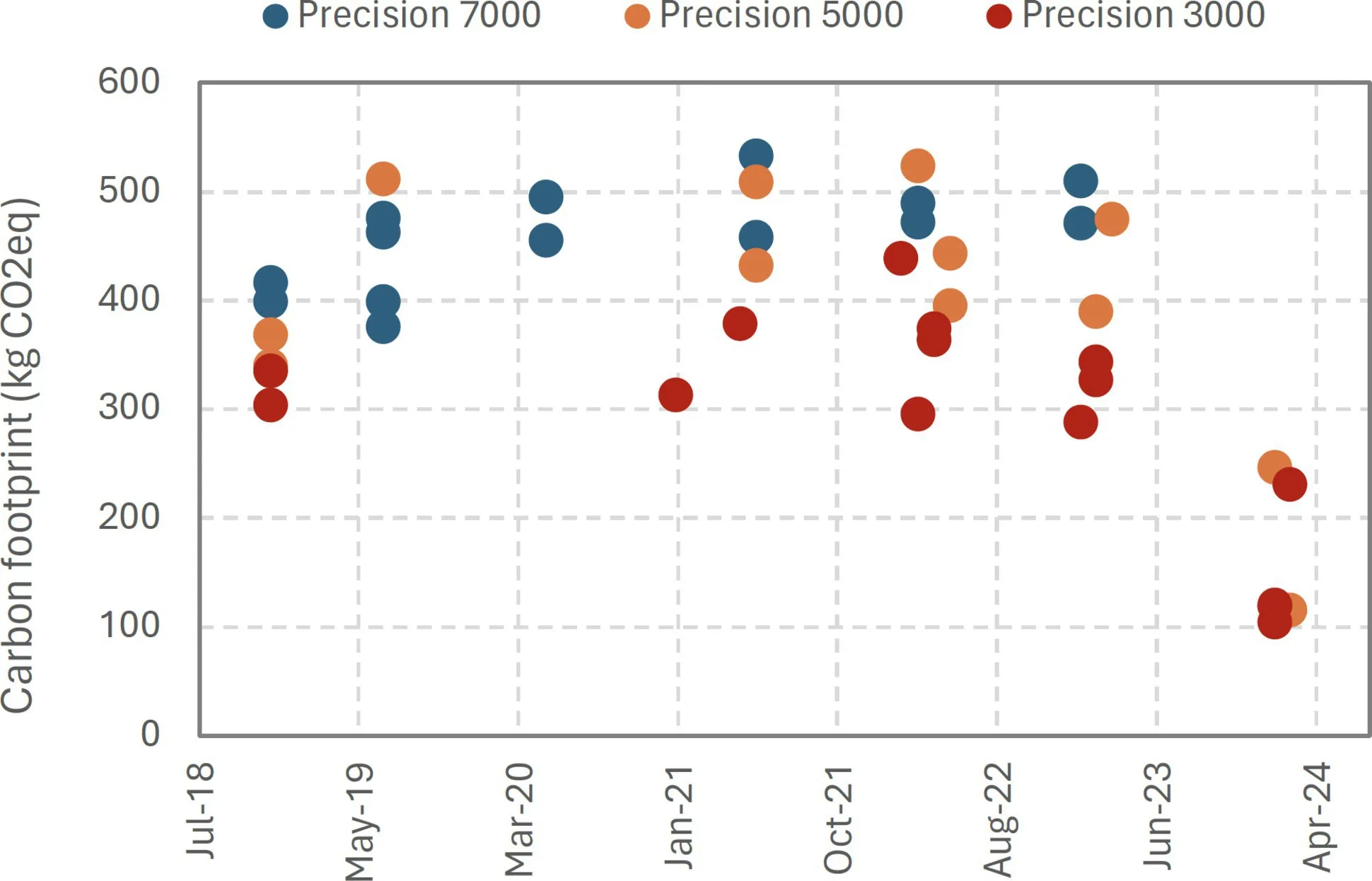

Looking at Dell, we note a slightly different outcome. The data in Figure 6 reports the carbon footprint for the 3000, 5000, and 7000 Dell Precision laptops. The per-device carbon footprint increased from 2018 until 2023 for the 5000 (CAGRC/D = +4.1%) and 7000 (CAGRC/D = +3.8%) laptops, while being invariant for the 3000 laptops. Note that the carbon footprint drastically drops for the most recent laptops released in February and March 2024, but this is due to a change in carbon accounting from MIT’s PAIA tool to Dell’s own ISO14040-certified LCA tool.

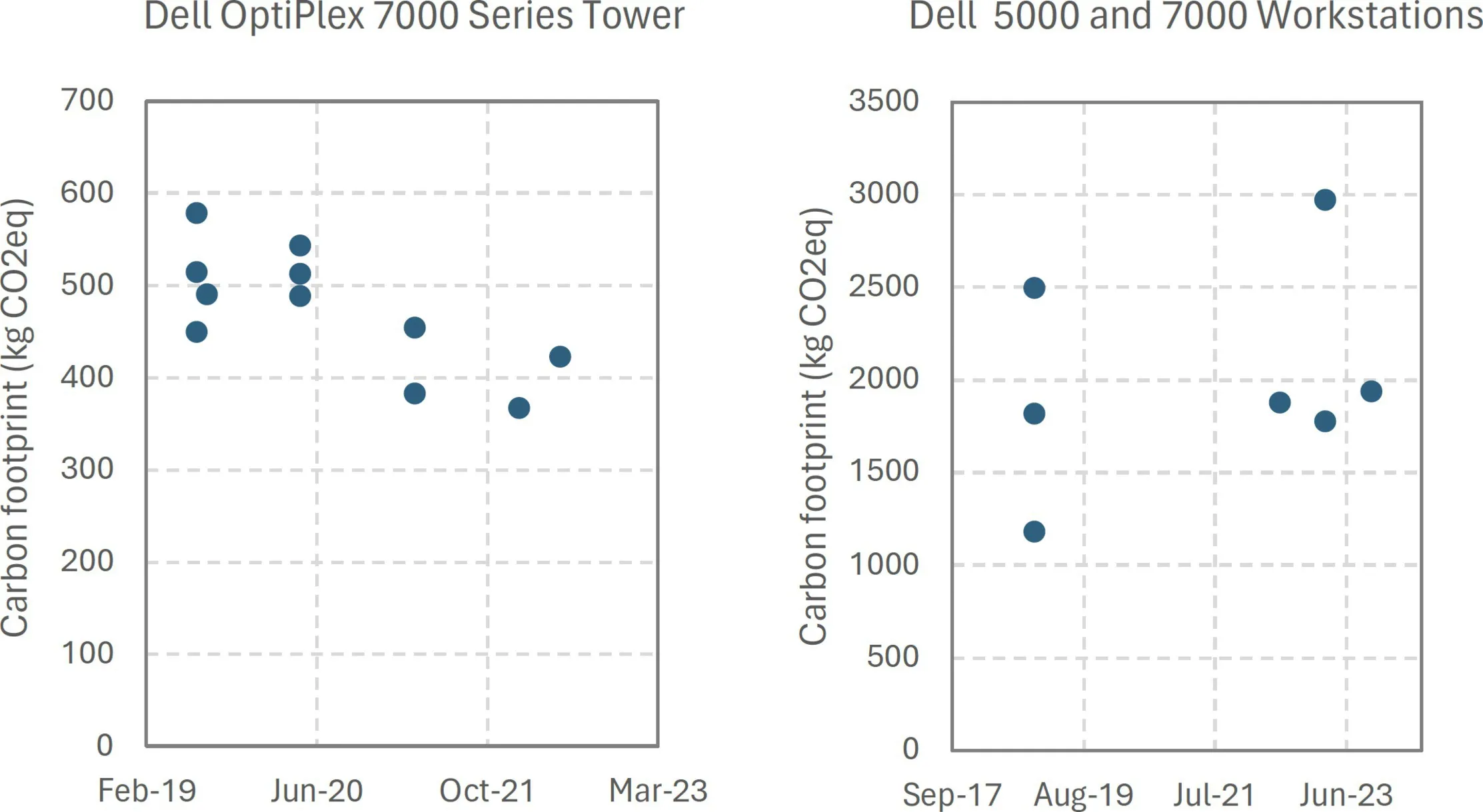

Desktops and workstations. The outlook is mixed for desktops and workstations, with some trends increasing and others decreasing. Figure 7 shows carbon footprint for the Dell OptiPlex 700 Series Tower desktop machines (left) decreasing at a rate of CAGRC/D = −8.1% but increasing at a rate of CAGRC/D = +4.0% for Dell Workstations 5000 and 7000 Series (right).

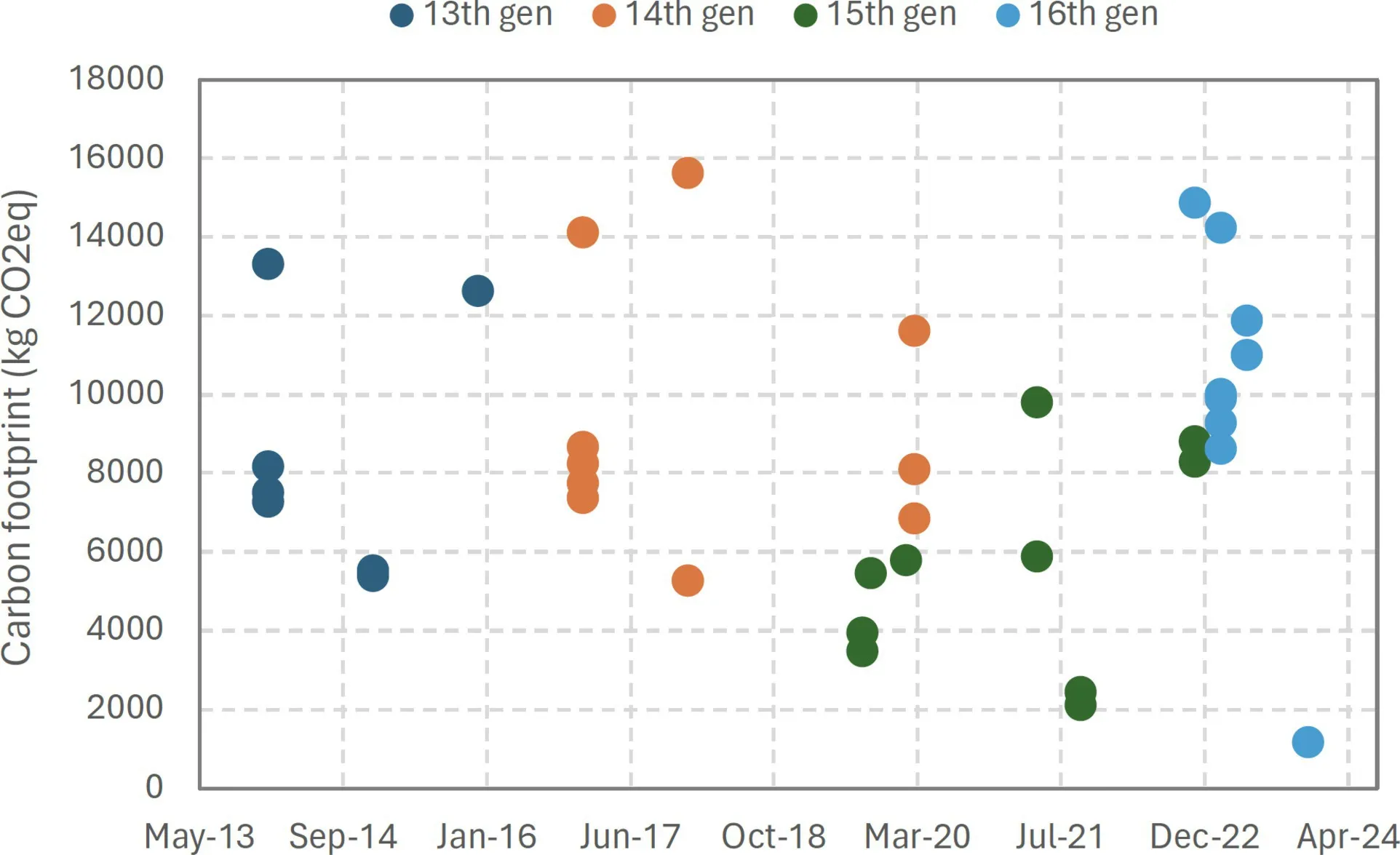

Servers. Figure 8 reports the carbon footprint for Dell PowerEdge rackmount ‘R’ servers across four generations (13th, 14th, 15th, and 16th); this includes Intel- and AMD-based systems. Server carbon footprint numbers are subject to its specific configuration and deployment, more so than (handheld) consumer devices for at least two reasons. First, because the operational footprint tends to dominate for servers—unlike handheld devices which are mostly dominated by their embodied footprint13—the location of use (and its power-grid mix) has a substantial impact. Second, hard-drive capacity, memory capacity, and processor configuration heavily impact the overall carbon footprint. Overall, server carbon footprint seems to be relatively constant over the past decade, although we note a small increase in average carbon footprint from the 13th to the 16th generation (CAGRC/D = +1.8%). The carbon footprint of a typical high-end server tends to range between 8,000kg and 15,000kg CO2eq over the past decade. Entry-level servers tend to have a lower carbon footprint below 6,000kg CO2eq with a downward trend in recent years. (See the couple of data points in the bottom right corner in Figure 8.)

Discussion. It is (very) impressive to note that the compute power of computing devices has dramatically increased over the past years while not dramatically increasing the per-device carbon footprint. In fact, for several computing devices, we note a decreasing trend in per-device carbon footprint—see also Table 2 for a summary—especially in recent years, which is particularly encouraging to note.

| Device | Model | Period | CAGR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smartwatch | Apple Watch | 2019–2023 | -7.7% |

| Smartphone | Apple iPhone Pro Max | 2019–2023 | -7.1% |

| Apple iPhone Pro Max | 2021–2023 | -3.3% | |

| Google Pixel | 2021–2023 | -10.5% | |

| Laptop | Apple MacBook Pro 16-in. | 2019–2023 | -6.9% |

| Apple MacBook Air 13-in. | 2018–2024 | -5.1% | |

| Dell Precision 7000 | 2018–2023 | +3.8% | |

| Desktop | Dell OptiPlex 700 | 2019–2022 | -8.1% |

| Dell Workstations 5000 and 7000 | 2018–2023 | +4.0% | |

| Server | Dell PowerEdge rackmount | 2014–2024 | +1.8% |

One may wonder whether the recent reduction in per-device carbon footprint comes from reductions in embodied or operational footprint. Upon closer inspection, it turns out that the key contributor to the total reduction in carbon footprint varies across device types. For the Apple smartwatches, the relative decrease in embodied footprint (−7.4% per year) is more significant than the decrease in operational footprint (−2.8% per year). Also, for the MacBook Pro 16-in. laptops, the embodied footprint has decreased at a faster pace (−7.9% per year) than the operational footprint (−3.5% per year). In contrast, for the iPhone Pro Max smartphones, we note a more significant reduction in operational footprint (−11.2% per year) than in embodied footprint (−5.7% per year). For the MacBook Air 13-in. laptops, we even note an increase in operational footprint (+14.9%) while the embodied footprint trends downward (−5.6%).

Overall, per-device carbon footprint decreases for most of the devices analyzed in this work, and in cases where it increases, the increase is limited. The reason for these trends is mixed. The question now is whether this overall declining trend in per-device carbon footprint is sufficient to reduce the overall environmental footprint of computing, and, even better, for meeting the Paris Agreement, which we discuss next.

Quantifying the Sustainability Gap

Recall that population and affluence increase, (CAGRP = +0.9%) and (CAGRD/P = +8.4%), respectively. Technology, on the other hand, seems to decrease for many devices, ranging from CAGRC/D = −3.3% to −10.5%, while increasing for others from +1.8% to +4.0%, as summarized in Table 2. The question now is whether these trends lead to an overall increase or decrease in the environmental footprint of computing.

Figure 9 predicts the overall carbon footprint for the next decade normalized to present time for a variety of typical per-device carbon footprint scaling trends, that is, CAGRC/D = +4%, −5%, −10%. In addition, we consider the following three scenarios:

Scenario #1: Status quo per-device footprint. If we were to keep the carbon footprint per device constant relative to present time, that is, CAGRC/D = 0%, the total carbon footprint would still increase substantially (CAGRC = +9.4%). This is simply a consequence of the growing population and the increasing affluence or number of computing devices per person. Because this is an exponential growth curve, this implies that the total carbon footprint of computing would increase by a factor 2.45× over a decade. In other words, even if we were to keep the carbon footprint per device constant, the total carbon footprint of computing would still dramatically increase.

Scenario #2: Status quo overall footprint. If we want to keep the overall carbon footprint of computing constant relative to the present time, that is, CAGRC = 0%, we need to reduce the carbon footprint per device by CAGRC/D = −8.6% per year. This is to counter the increase in population and number of devices per person. Reducing the carbon footprint per device by 8.6% year after year for a full decade is a non-trivial endeavor. To illustrate how challenging this is, consider a device that incurs a carbon footprint of 100kg CO2eq. Reducing by 8.6% per year requires that the carbon footprint is reduced to 40.6kg CO2eq within a decade; in other words, the carbon footprint needs to reduce by more than a factor 2.4× over a period of 10 years.

Scenario #3: Meeting the Paris Agreement. To make things even more challenging, to meet the Paris Agreement, we need to reduce global GHG emissions by a factor 2.2× over a decade or by 7.6% per year, that is, CAGRC = −7.6%. To achieve this, we would need to reduce the carbon footprint per device by 15.5% per year, that is, CAGRC/D = −15.5%. This implies that we need to reduce the carbon footprint per device by a factor 5.4× over a decade.

It is clear from Figure 9 that the impact of the per-device carbon footprint scaling trend has a major impact on the overall environmental footprint. Relatively small differences in CAGR lead to substantial cumulative effects over time due to the exponential growth curves. In particular, the status quo per-device carbon footprint (CAGRC/D = 0%) leads to a 2.45× increase in overall carbon footprint over a decade, while the Paris Agreement requires that we reduce the total carbon footprint by 2.2× (CAGRC/D = −15.5%). Even if we were to reduce the per-device carbon footprint at a relatively high rate (CAGRC/D = −8.6%) to maintain a status quo in total carbon footprint, the gap with the Paris Agreement would still increase at a rapid pace.

As noted from Table 2, most devices do not follow a trend that complies with these required trends: Reported per-device carbon footprint CAGRs are not anywhere close to the required CAGRC/D = −15.5% (to meet the Paris Agreement) nor do they uniformly meet the CAGRC/D = −8.6% (to keep total carbon footprint constant relative to present time). To close the sustainability gap, one needs to reduce the per-device carbon footprint by 15.5% per year for the next decade. This implies that the computing industry should do more to keep its carbon footprint under control. This leads to the overall conclusion that there is a substantial gap between the current state of affairs versus meeting the Paris Agreement. Bridging the sustainability gap is a non-trivial and challenging endeavor, which will require significant innovation in how we design and deploy computing devices beyond current practice.

The Socio-Economical Context

The above analysis assumes that the world population and the number of devices per person will continue to grow at current pace for the foreseeable future. The task of decreasing the carbon footprint per device by 15.5% per year to meet the Paris agreement can be loosened to some extent by embracing a certain level of sobriety in affluence, that is, limiting the number of devices per person. This requires a perspective on the socio-economical context of computing, which includes economic business models, regulation, and legislation.

The computing industry today is mostly a linear economy where devices are manufactured, used for a while, and then discarded. The lifetime of a computing device can be relatively short, for example, two to four or five years, leading to increased e-waste. Reusing, repairing, refurbishing, repurposing, and remanufacturing devices could contribute to a circular economy in which the lifetime of a computing device is prolonged, thereby reducing e-waste and tempering the demand for more devices.10 For example, Switzer et al.23 repurpose discarded smartphones in cloudlets to run microservice-based applications. Reducing the demand for devices could possibly relax the need for reducing per-device carbon footprints.

There is a moral aspect associated with reducing the demand for devices, which is worth highlighting. As mentioned previously, affluence is higher in the western world (North America and Western Europe) compared to other parts of the world and moreover it is increasing faster. From an ethical perspective, this suggests that the western world should make an even greater effort to reduce the environmental footprint of computing—in other words, we should not necessarily expect other parts of the world to make an equally big effort to solve a problem the western world is mostly responsible for. This implies that the western world should step up its effort in embracing sobriety (that is, consume fewer devices per person) and making individual computing devices even more sustainable.

In addition to transitioning toward a circular economy, other business models can also be embraced. Today, most cloud services are free to use, see for example social media, mail, Web search, and so on, while relying on massive data collection. Maintaining, storing, processing, and searching Internet-scale datasets requires massive compute, memory, and storage resources. According to a recent study by the International Energy Agency,15 datacenters are estimated to account for about 2% of the global electricity usage in 2022; and by 2026, datacenters are expected to consume 6% of the nation’s electricity usage in the U.S. and 32% in Ireland. Moreover, data storage incurs a substantial embodied footprint.24 The environmental footprint of free Internet services is hence substantial. Allowing low-priority files to degrade in quality over time could possibly temper the environmental cost for storage devices.26 But we could go even further by changing the business and usage models of Internet-scale services. Imposing a time restriction for uploaded content could possibly temper the demand for more processing power and storage capacity. We may want to limit how long we keep data around depending on its usefulness and criticality. To make it concrete: Do we really need to keep (silly) cat videos on the Web forever? Limiting to a day or a week may serve the need. Alternatively, or complementarily, one could demand a financial compensation from the customer for using online services. In particular, one could ask customers if they are willing to pay to keep their content online. For example, do you want to pay for your cat videos to remain online for the next month or year?

Transitioning to renewable energy sources (solar, wind, hydropower) is an effective method to reduce the carbon footprint of computing—as with any other industry. Renewables during chip manufacturing have the potential to drastically reduce a device’s embodied carbon footprint. Conversely, renewables at the location of device use drastically reduce a device’s operational emissions. This is happening today as renewables take up an increasingly larger share in the electricity mix.20 However, there are several caveats. First, total electricity demand increases faster than what renewables can generate, increasing the reliance on brown electricity sources (that is, coal and gas) in absolute terms.20 In other words, the transition rate to renewables is not fast enough to compensate for the increase in population and affluence. Second, the amount of green energy is too limited to satisfy all stakeholders. For example, Ireland has decided to limit datacenter construction until 2028 because allowing more datacenters to be deployed would compromise the country’s commitment that 80% of the nation’s electricity grid should come from renewables by 2030.16 Third, while renewables reduce total carbon footprint, it does not affect other environmental concerns, including raw material extraction, chemical and gas emissions during chip manufacturing, water consumption, impact on biodiversity, and so on.

The analysis performed in this paper considered computing as a standalone industry. But computing may enable other industries to become more sustainable, thereby (partially) offsetting its own footprint. This could potentially lead to an overall reduction in environmental footprint.19 For example, computer vision enables more efficient agriculture using less water resources and pesticides; artificial intelligence and machine learning could make transportation more environmentally friendly; smart grids that use digital technologies could increase the portion of renewables in the electricity mix in real time; or Internet-of-Things (IoT) devices could help reduce emissions in residential housing. While the anticipated sustainability gains in other industries may be substantial, one must be careful when analyzing such reports, that is, one has to carefully understand the assumptions and the associated limitations to fully grasp the validity of such analyses.21 Moreover, one must be wary of Jevons’ paradox as mentioned before: Making a product or service more carbon-friendly may lead to an increase in overall carbon footprint if the efficiency gain leads to increased deployment and/or usage. In other words, one should be aware of the bigger picture—unfortunately, holistic big-picture assessments are extremely complicated to make and anticipate.

Finally, regulation and legislation may be needed to temper the environmental footprint. The previously cited IEA report15 states that “regulation will be crucial in restraining data center energy consumption” while referring to the European Commission’s revised energy-efficiency directive. The latter entails that datacenter operators have to report datacenter energy usage and carbon emissions as of 2024, and they have to be climate-neutral by 2030. Further, the European Parliament adopted the so-called ‘right to repair’ directive, which requires manufacturers to repair goods with the goal of extending a product’s lifetime—thereby reducing e-waste and the continuous demand for new devices. Overall, innovation in regulation, legislation, and/or business models will be needed to incentivize (or even force) manufacturers, operators, and customers to temper the demand for more devices, while making sure that our computing industry can still thrive and generate welfare. This is a call for action for our community to reach out to psychologists, sociologists, law and policy makers, entrepreneurs, business people, and so on to holistically tackle the growing environmental footprint of computing.

Related Work

Our computer systems community recently started considering sustainability as a design goal, and prior work focused mostly on characterizing,8,12,13,24 quantifying,9,14,17 and reducing1,4,5,22,25 the carbon footprint per device. However, as argued in this paper, to comprehensively and fully understand and temper the environmental footprint of computing, one needs to consider the socio-economic context within which we operate. Population growth and increased affluence is a current reality we should not be blind to and which impacts what we must do to reduce the overall environmental impact of computing.

Conclusion

This paper described the sustainability gap and how it is impacted by population growth, the increase in affluence (increasing number of devices per person), and the carbon intensity of computing devices. Considering current population and affluence growth, the carbon intensity of computing devices needs to reduce by 9.4% per year to keep the total carbon footprint of computing constant relative to present time, and by 15.5% per year to meet the Paris Agreement. Several case studies illustrate that while (some) vendors successfully reduce the carbon footprint of devices, it appears that more needs to be done. A concerted effort in which both the demand for electronic devices and the carbon footprint per device is significantly reduced on a continuous basis for the foreseeable future, appears to be inevitable to keep the rising carbon footprint of computing under control and, if possible, drastically reduce it.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment