Adopting and implementing digital automation technologies, including artificial intelligence (AI) models such as ChatGPT, robotic process automation (RPA), and other emerging AI technologies, will revolutionize many industries and business models. It is forecasted that the rise of AI will impact a wide range of job functions and roles. White-collar positions such as administrative, customer service, and back-office roles will all be impacted by AI-fueled digital automation. The adoption of digital workers is currently positioned in the early adopter phase of the product lifecycle.1 AI-driven digital workers are expected to substantially alter many white-collar tasks, including finance, customer support, human resources, sales, and marketing.42

A study from Oxford University and Deloitte predicts AI is a significant risk to the white-collar workforce. According to the study, approximately 47% of white-collar jobs could be eliminated or reduced within 20 years due to AI-powered automation of critical business functions.4 According to Bill Gates “[t]he development of AI is as fundamental as the creation of the microprocessor, the personal computer, the Internet, and the mobile phone; entire industries will reorient around it. Businesses will distinguish themselves by how well they use it.”13 Digital workers, or software robots, automate routine tasks, process and analyze large volumes of data, and interact with other software systems. They have been successfully integrated into the banking, healthcare, and customer service sectors, among several other industries, enhancing efficiency and reducing human error.25

Over the past several years, AI has advanced rapidly, particularly with the development of large language models (LLMs). These LLMs have enabled machines to understand language and generate human-like text with unprecedented accuracy, and have opened new avenues for applications such as chatbots and virtual assistants. One such LLM is ChatGPT, developed by OpenAI, a state-of-the-art language model leveraging unsupervised learning to generate contextually relevant and coherent text. Its capabilities extend to text translation, summarization, software code generation, and even creative writing, marking its potential as a disruptive force in the white-collar job market.37

Key Insights

Anthropomorphism drives AI adoption: This study shows that how human-like an AI agent appears has a greater influence on hiring decisions than trust. Familiarity fosters psychological comfort, making anthropomorphism a critical factor in AI acceptance.

Distrust triggers emotional reactions: While trust impacts hiring intentions, distrust plays a stronger role in feelings of embarrassment when disclosing sensitive information. Addressing distrust is essential for improving human-AI interactions.

AI’s growing role in white-collar work: AI-driven digital workers are reshaping white-collar jobs. Their success will depend not only on efficiency and accuracy but also on perceived anthropomorphism and ease of use.

Trust and distrust are distinct: Trust encourages AI adoption, but distrust is a separate construct with unique effects on user experience. Managing both is key to evaluating AI adoption in professional settings.

Several technologies complement and extend the capabilities of AI use cases such as RPA, often simply referred to as “bots.” Bots automate routine and repetitive tasks. Leading technology companies are expanding the capabilities of RPA solutions to include advanced analytic and cognitive features. Technology companies are positioning these new features of RPA solutions as digital workers. A digital worker is much more capable than a bot. A bot can be programmed to execute tasks, while a digital worker can do much more. Digital workers understand human interaction. They are configured to respond to questions and act on a human’s behalf. In theory, however, humans continue to have control and authority over digital workers while realizing the benefits of enhanced productivity. They improve and augment human interaction by combining AI, machine learning, RPA, and analytics while automating business functions from beginning to end. Forrester Research defines digital worker automation as a combination of information architecture (IA) building blocks, such as conversational intelligence, that works alongside employees.25

Digital workers enabled by technology such as AI, voice recognition, and natural language processing (NLP) can understand commands, respond to questions, and act on requests such as playing music, checking the weather, or placing grocery orders.21 In addition to voice recognition, it is now possible to interact with a digital worker via a webcam. Digital workers can also recognize and react to expressions and emotions and have advanced conversational capabilities. They have human-like features that can be tailored to the role, language, culture, personality, and demographic factors of their human communication partners. The technology that enables digital workers is progressing rapidly and is creating a sizable market opportunity for software companies that build and deliver digital workers. The successful implementation of digital workers represents a potential disruption to many components of the white-collar workforce, both in job displacement and job transformation.

Trust and AI Anthropomorphism

Trust is a central element in how we interact with other people. It is “the willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other will perform a particular action important to the trustor, irrespective of the ability to monitor or control that other party.”30 In essence, trusting as it relates to other people means putting aside concerns about the possible inappropriate behavior of the party being trusted.28 The psychological importance of trust is based on people’s need to understand their social environment. However, doing so is complicated because that social environment is overwhelmingly complex considering that each party involved is a free agent whose behavior may not always be rational.14,28 Confronted with that overwhelming task, people make assumptions about what other people will and will not do. Those assumptions are what trust is about.15 Trusting thus involves assuming away many possible behaviors so that the social environment may become comprehensible.15 That is, by trusting others, people set aside their concerns about the many possible behaviors those others may engage in and adopt instead an assumption that those others will behave as expected. Trust is important in business contexts, perhaps even more than cost because it subjectively reduces business-related risks and uncertainty.17 Trust and control complement and substitute for each other.43

In the context of AI, the perceived anthropomorphism of an AI chatbot can increase this trust,5,20 as shown by previous research that has mainly examined innocuous contexts, such as asking Siri questions35 or involving riskless artificial experimental contexts.8,44 Anthropomorphism is the attribution of distinctly human attributes to a non-human agent,10 consequently treating artificial artifacts as though they are human and even forming an attachment to that non-human agent.3 Anthropomorphism is becoming key to the acceptance of robots too.22 The underlying theory used in much of this research stems from the “computers are social actors” (CASA) paradigm,38 which suggests that people treat computers, and by extension AI agents, as they treat other people. The logic often associated with perceived anthropomorphism is that initial trust (that is, before knowing the other party31) is influenced by familiarity, which is increased when the AI looks and/or behaves like a human.2 This need to understand the environment in which one interacts through increased familiarity is a central argument for why anthropomorphism may increase trust.2,11

Distrust

Our contention in this study is that distrust should be added to the fray. Trust and distrust are two distinct but related constructs that operate in tandem.27,34 As fMRI research shows, trust is predominantly a rational assessment aimed at building cooperation (because the neural correlates of trust are mainly associated with brain regions that deal with higher-order decision-making; for reviews, see Krueger and Meyer-Lindenberg24). Distrust, in contrast, is mainly associated with brain regions that deal with fear and emotional responses.9,39 Indeed, distrust has been discussed as an emotional response to a perceived threat.41 Trust and distrust are intertwined and together determine how people approach a relationship, but they are clearly distinct phenomena.27 What follows is that in contrast to the aforementioned relationship about trust in AI (see also the summary in Beck et al.2), where the discussion centers on trust being essential to promote interaction, or at least intentions to do so, it is possible that distrust will also play a key role.

To better understand the role of distrust, drawing on research on interpersonal relationships,27 people consider not only their initial trust but also their initial distrust when assessing people or organizations they do not know. In this dual consideration, initial trust is about assessing the other party with the objective of creating a constructive relationship based on the assumed trustworthiness of the other party.30 It is about setting aside concerns about the possible unconstructive behavior of that other party.15 In contrast, distrust is precisely about paying close attention to such concerns.27 To account for that distinction, this study looks at such concerns in the context of disclosing potentially embarrassing (as an exemplar of an emotional context) information to a CPA. Past research that did not consider distrust has shown that low trust is a predictor of embarrassment in providing information, and, moreover, that consumers prefer an AI avatar over a human CPA because they believe there will be no embarrassing social judgement by an avatar and hence, they would be more open to disclosing information.23

According to the literature survey by Israelsen and Ahmed,20 distrust in the context of AI avatars has been largely ignored in previous research on trust in AI agents, However, as AI agents move from innocuous tasks into more risky areas, distrust should become a key consideration. This is especially true given that even the popular press is now reporting on its tendency to provide “hallucinational” responses.6 Such risks are prominent in the context of this study, which deals with providing tax information to a CPA, where accurate information is critical and where there is a distinct risk of identity theft (which is one of the reasons CPA is a legally regulated profession).

The Experiment

In our experiment, people were tasked with hiring a CPA to help them prepare their annual tax returns after losing $60K on the stock market (data was collected in March 2023 when the market was going down). In this between-subjects design experiment, people were randomly assigned to either a human CPA agent or an explicit AI avatar CPA agent. Then they filled in a questionnaire about their trust and distrust in the agent, its anthropomorphism and intelligence combined with their intentions to hire it, and how comfortable they would feel in disclosing information to that agent. The questions were identical in both treatments. The only difference was whether they were exposed to a human agent or an avatar. The study was approved by the Drexel University IRB protocol #2303009777.

Survey participants were recruited and paid using the Centiment survey recruitment service. The use of such panel administrators to collect data is becoming more prevalent, with almost 20% of articles in leading management science journals applying it as of 2020, up from about 10% in 2010.19

The target audience was people in the U.S. 18 or older and within 5% of the census average for age, gender, and race/ethnicity. The scales were adapted from previous studies: Trust based on Gefen et al.,14 distrust on McKnight and Choudhury,33 anthropomorphism on Bartneck et al.1 and Moussawi et al.,35 and intelligence on Moussawi et al.35 In the above, Gefen et al.14 showed that potential adopters of what was then a new technology are influenced not only by their rational assessments of its perceived usefulness and ease of use but, importantly, by whether they trust the organization behind the IT. Adding distrust, McKnight and Choudhury33 showed that trust and distrust are two unique constructs that have opposite effects on willingness to share information and purchase. Embarrassment was based on the themes in Dahl et al.7 The Intended Hiring scale was developed for this study. All the questionnaire items, other than the demographics, used a seven-point Likert scale anchored at 1 = “Strongly Disagree,” 2 = “Disagree,” 3 = “Somewhat Disagree,” 4 = “Neither Agree nor Disagree,” 5 = “Somewhat Agree,” 6 = “Agree,” and 7 = “Strongly Agree.”

After clicking their consent to participate, subjects were asked to watch a 60-second video clip. This clip was either a real clip of an adult Caucasian woman in her thirties or forties advertising her CPA company, or an equivalent clip of an avatar, also of an adult Caucasian woman in her thirties or forties, but instead of talking about her company, she admits to being an avatar. The avatar was created with software from Synthesia, which enables content creators to use a wide range of lifelike avatars with customizable demographic characteristics and the ability to speak in more than 120 languages and accents.

Below is the text of the human agent:

We want to understand your personal and business goals. Only then can we customize your needs into the right tax strategies that work to your advantage. Solid planning can protect your assets, maximize their value, and minimize your tax burden. Your financial situation can change as time goes on and most certainly tax laws will change as well. Our firm constantly monitors federal, state, and local tax changes that may affect you. We form a partnership of communication with our clients so when conditions change, we’re ready to protect you from unnecessary tax expense. Our firm is here to help you with personal taxation and savings opportunities, choosing the right business entity for tax purposes, employee benefit, and retirement programs; education and gift-giving programs; tax considerations and retirement benefits; and trust and estate planning. If you have any questions regarding your business, we can help. Call us today.

This text was modified for the avatar by adding a preface saying “My name is Anna and I am a digital worker that has been trained by an artificial intelligence tool to be a tax expert. You will be able to interact with me by using a webcam and microphone,” and replacing “Call us today” with “If you have any questions, I am available 24/7 and only a click away to assist you.”

After clicking an acknowledgment that they watched the video, the subjects were told that:

Unfortunately, you lost $60K due to selling shares in a company on the stock market . You will need to discuss with the expert what steps you need to take to report this loss on your U.S. Federal income taxes.

After that introduction, the subjects proceeded to complete the survey; survey items are shown in Table 1. We added two manipulation-check questions right after the video clip: “The tax expert in the video (henceforth “the expert”) appears to be a real human being” and “The expert seems energetic.” The human was significantly (t=9.86, p-value<.001) assessed as more human (mean=5.79, std.=1.51, n=408) than the avatar (mean=4.62, std.=1.93, n=411), and likewise more energetic (t=7.83, p-value<.001; human mean=5.29, std.=1.36, n=389; avatar mean=4.43, std.=1.69, n=410).

| Trust in the Agent | Loading (SE) |

|---|---|

| I expect that the expert will be honest with me. | 0.811 (.014) |

| I expect that the expert will show care and concern towards me. | 0.782 (.015) |

| I expect that the expert will provide good tax advice to me. | 0.855 (.011) |

| I expect that the expert will be trustworthy. | 0.889 (.009) |

| I expect that I will trust the expert. | 0.872 (.010) |

| Distrust in the Agent | |

| I am not sure that the expert will act in my best interest. | 0.807 (.015) |

| I am not sure that the expert will show adequate care and concern toward me. | 0.809 (.015) |

| I am worried about whether the expert will be truthful with me. | 0.838 (.013) |

| I am hesitant to say that the expert will keep its commitments to me. | 0.785 (.016) |

| I distrust the expert. | 0.769 (.017) |

| Perceived Agent Intelligence | |

| The expert speaks in an understandable manner. | 0.597 (.024) |

| The expert will be friendly. | Dropped |

| The expert will be respectful. | 0.770 (.016) |

| I expect that the expert will complete tasks quickly. | 0.717 (.019) |

| I expect that the expert will understand my requests. | 0.817 (.013) |

| I expect that the expert will communicate with me in an understandable manner. | 0.836 (.012) |

| I expect that the expert will find and process the necessary information to complete tasks relating to my needs. | 0.871 (.010) |

| I expect that the expert will provide me with useful answers. | 0.874 (.010) |

| I expect that the expert will be interactive. | Dropped |

| I expect that the expert will be responsive. | 0.783 (.015) |

| Perceived Agent Anthropomorphism | |

| The expert seems happy. | 0.753 (.017) |

| The expert will be humorous. | 0.574 (.025) |

| The expert will be caring. | 0.799 (.015) |

| The expert seems energetic. | 0.866 (.011) |

| The expert seems lively. | 0.871 (.011) |

| The expert seems authentic. | 0.840 (.012) |

| Intention to Hire | |

| I plan to contract with this expert to prepare my tax returns. | 0.823 (.013) |

| Hiring this expert to prepare my tax returns is something I would consider seriously. | 0.918 (.007) |

| I would pay this expert to prepare my tax returns. | 0.920 (.007) |

| Hiring this expert to prepare my tax returns is okay by me. | 0.909 (.008) |

| Being Embarrassed | |

| I expect that I will feel embarrassed discussing my tax question with the expert. | 0.864 (.011) |

| I expect that I will be uncomfortable discussing my tax question with the expert. | 0.915 (.009) |

| I expect that I will feel awkward discussing my tax question with the expert. | 0.892 (.010) |

The age range of the respondents was: 30 between 18-19, 91 between 20 and 24, 172 between 25 and 34, 171 between 35 and 44, 132 between 45 and 54, 118 between 55 and 64, 112 between 65 and 74, and 41 were 75 and older; two did not answer. Moreover, 382 participants were male, 482 female, and six declined to answer.

In terms of education level, 30 had less than a high school education, 246 graduated high school, 222 had some college experience, 94 had earned a two-year degree, 161 had earned a four-year degree, 93 had earned a professional degree, 21 held a doctorate, and three preferred not to say.

As far as reported ethnicity, 520 were Caucasian, 171 were African American, 21 were American Indian or Alaska Native, 30 were Asian, four were Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, 122 were Latino (noted as Latin X in the survey), and 58 chose “Other” (people were allowed to select more than one ethnicity). After deleting rows with missing data list-wise, the combined sample size used for data analyses was n = 781.

Data Analysis

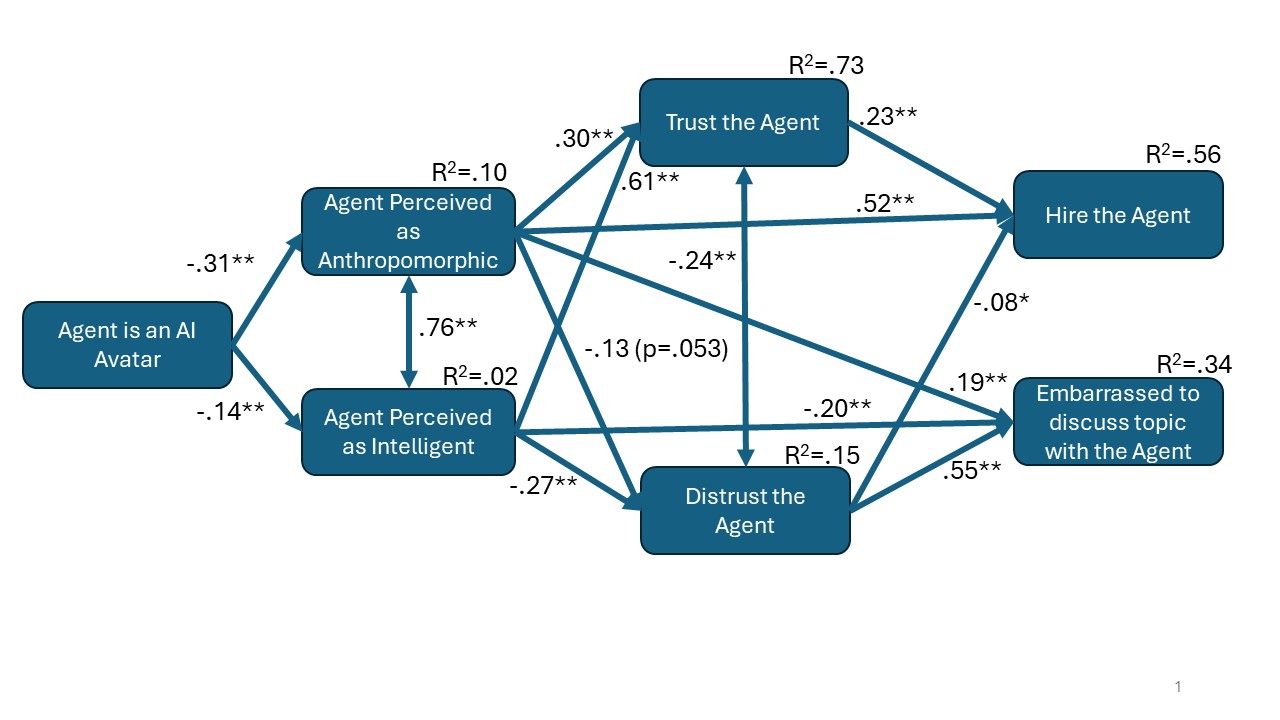

The data was analyzed using Mplus, a covariance structural equation modeling (CBSEM) package that assesses the measurement model (how the items load on their assigned latent construct in a confirmatory factor analysis, CFA) simultaneously with the structural model (how these latent constructs relate to each other) using maximum likelihood.36 We posited that people would be less trusting and more distrustful of an avatar—perceiving it as less anthropomorphic and less intelligent—and that this would predict their willingness to hire the agent (whether human or avatar) and the level of embarrassment they would feel discussing their tax situation with the agent. The overall model fit indices were: , RMSEA = .061, CFI = .931, and TLI = .922. Those numbers indicate a good model fit.16 Standardized item loadings are shown in Table 1. All the items loaded significantly at a p-value < .001 level. The latent constructs to which the items refer are shown in bold.

The standardized loadings of the structural model appear in the the Figure. Paths not shown are insignificant (Perceived Agent Intelligence on Intention to Hire Γ = -.010, SE = .060, p-value = .865; Trust in the Agent on Being Embarrassed Γ = .031, SE = .075, p-value = .675; correlation of Being Embarrassed with Intention to Hire y = .045, SE = .042, p-value = .287). Importantly, viewing the clip with an avatar rather than a human CPA (avatar in the Figure) did not affect Intention to Hire (β = .029, SE = .028, p-value = .307), Being Embarrassed (β = .036, SE = .034, p-value = .287), Trust in the Agent (β = .004, SE = .024, p-value = .858), Distrust in the Agent (β = .024, SE = .038, p-value = .530), but did significantly decrease Perceived Agent Anthropomorphism (β = -.307, SE = .034, p-value <.001) and Perceived Agent Intelligence (β = -.138, SE = .036, p-value <.001). Age decreased Intentions to Hire (β = -.140, SE = .026, p-value <.001) and Being Embarrassed (β = -.144, SE = .032, p-value = .287), but was insignificant on Trust in the Agent (β = .002, SE = .022, p-value = .932), Distrust in the Agent (β = -.034, SE = .035, p-value = .337), Perceived Agent Anthropomorphism (β = -.009, SE = .036, p-value = .809), and Perceived Agent Intelligence (β = .000, SE = .037, p-value= .998). Gender decreased Intention to Hire (β = -.086, SE = .026, p-value = .001) but was insignificant on Being Embarrassed (β = -.003, SE = .032, p-value = .928), Trust in the Agent (β = .030, SE = .022, p-value = .181), Distrust in the Agent (β = .028, SE = .036, p-value = .437), Perceived Agent Anthropomorphism (β = -.057, SE = .036, p-value = .111), and Perceived Agent Intelligence (β = -.014, SE = .037, p-value = .707).a

Verifying the importance of distrust, we calculated its effect size on Intention to Hire (f2 = .004, a practically zero effect and with an R2inc = .004) and on Being Embarrassed (f2 = .316, a large effect with an R2inc = .240). This suggests that while distrust does significantly affect Intention to Hire its size effect is negligible. This analysis also revealed, interestingly, that when removing the path from Distrust to Being Embarrassed, Trust became a significant predictor of Being Embarrassed (β = -.274, SE = .111, p-value = .014), as reported by Kim et al.,23 who excluded Distrust from their model. However, excluding Distrust brought the R2 of Being Embarrassed to only .10.

As additional verification of the analysis, to account for the inevitable common method variance in questionnaire data, we applied the marker-variable technique that Malhotra et al.29 recommended. The standardized results are essentially the same except that now the path from Distrust to Hire Intentions is more significant (β = -.084, SE = .030, p-value = .005), but the effect size remained practically 0 at f2 = .005. This indicates that while CMV may have a minor impact, the substantive conclusions of our study are robust.

Descriptive statistics of the latent constructs are shown in Table 2. The T column shows the t-test values between the human CPA agent and the AI avatar CPA agent. All the t tests are significant at the .01 level except Being Embarrassed, which is insignificant (p-value = .239). Subjects trusted the avatar less, distrusted it more, perceived it as less anthropomorphic and less intelligent, and were less inclined to hire it, even though that made little difference on how embarrassed they felt about discussing their tax situation with it.

| Human Agent | AI Avatar Agent | T | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (std.) | N | Mean (std.) | |||

| Trust in the agent | 407 | 5.58 (1.19) | 439 | 5.18 (1.41) | 4.48 | |

| Distrust in the agent | 391 | 3.58 (1.47) | 416 | 3.88 (1.49) | -2.87 | |

| Perceived agent anthropomorphism | 389 | 5.15 (1.05) | 410 | 4.42 (1.39) | 8.36 | |

| Intention to hire | 380 | 4.77 (1.49) | 406 | 4.22 (1.79) | 4.74 | |

| Being embarrassed | 381 | 3.20 (1.61) | 407 | 3.33 (1.64) | -1.18 | |

| Perceived agent intelligence | 389 | 5.61 (1.02) | 410 | 5.35 (1.14) | 3.44 | |

Discussion

According to the results, it is not exposure to an AI agent that makes a difference, but rather that participants in the study deemed the avatar to be less anthropomorphic and less intelligent. As the CBSEM analyses show, this fully mediated their trust and distrust in the agent and, subsequently, their hiring intentions and embarrassment. This supports previous research on how anthropomorphism builds trust, suggesting that the barrier to engaging digital workers (in this case CPAs) could be overcome, at least in part, by increasing people’s perceptions of their anthropomorphism. To the best of our knowledge, no academic empirical research exists which has explicitly examined distrust’s role in the context of AI avatar adoption. Because trust and distrust do not constitute two ends of a single continuum, but rather are separate constructs, as shown in this study too, the study of both trust and distrust complements the existing literature.

Specifically, the study revealed the following: Hiring an AI avatar, that is, starting a relationship with it, is mostly about its anthropomorphism (with a standardized coefficient more than twice that of trust) and then about trust (with a standardized coefficient almost three times that of distrust). However, when it comes to the embarrassment involved in the relationship (as opposed to its initiation), it is not trust but distrust and, to a lesser extent, anthropomorphism that is at play. Thus, removing distrust from the picture might have little impact on the decision to start a relationship, but it is central to how people feel embarrassed about that relationship.

The results also substantiate the central role of perceived anthropomorphism in human perception of AI avatars and their adoption. Current research holds that trust is central to the adoption of AI and is built through anthropomorphism.2,20 What the data tells us, however, is that while trust is important, perceived anthropomorphism is the key consideration, more so than trust. Moreover, the data analysis also shows that beyond perceiving the avatar as less anthropomorphic and less intelligent, the rest of the model was not affected by whether the participants were exposed to a human agent or to an AI avatar agent. That may lend credence to viewing trust in an avatar as a matter, extrapolating from Luhmann,28 of understanding what the AI is doing. As such, it is mostly anthropomorphism, and this applies to both the human CPA and the AI, that determines initial willingness to hire a CPA in such situations. Trust is important, and anthropomorphism engenders it, but it is anthropomorphism more than trust that counts in the decision to hire an agent. Distrust plays a distinctly different role, being related to information sharing embarrassment.

Key Takeaways

Critical role of distrust. This study uncovers the critical but separate roles of distrust and trust in the acceptance of, and embarrassment with, AI-powered digital workers compared to a human CPA. While trust increases the willingness to engage with AI for tasks such as hiring a CPA for tax services, distrust, rather than trust, influences the embarrassment emotional response when interacting with such an agent. This finding is based on the results of the experiment, which show a significant correlation between distrust and embarrassment, suggesting an expanded understanding of AI engagement beyond traditional trust theories and research.

Managing distrust. As the ability to distinguish between human and AI agents decreases with the increase of the anthropomorphism of AI, there should be a greater realization that distrust is a key element in this process. The role of distrust as revealed in this study is mainly about its correlation with embarrassment in disclosing information. In the case of hiring a CPA, disclosing embarrassing information might be clearly essential. Moreover, adding distrust to the model shows that it is distrust, rather than low trust as claimed by previous research,23 that is correlated with being embarrassed about providing information. This indirectly supports the claim that low trust is not the same as distrust.27,32 As Table 2 shows, the subjects were not more or less embarrassed in expecting to talk to a human CPA than to an AI avatar; this may also suggest that the issue is distrust rather than interacting with an AI avatar.

AI anthropomorphism. This research highlights the central role of anthropomorphism in people’s willingness to adopt digital workers by showing that anthropomorphism fully mediates the effects of exposure to an AI avatar on how likely people are to trust them and intend to use them. This role of anthropomorphism might be rationally surprising because avatars are not subject to the same legal oversight that human CPAs are, but it shows how much AI adoption is about the psychology of the familiar. Indeed, familiarity builds trust.18 Moreover, anthropomorphism directly affects behavioral intentions and increases it even more than trust does, even though the theory adapted by much previous research was that trust was a crucial mediator in that process.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment