Imagine trying to create the sensory impression of an object, say, the vibrant beauty of a sunflower. It is not just about visualizing its colors but also about feeling the textures and perceiving the delicate fragrances, all encapsulated within an event. This could be re-created as part of an art exhibition (for example, the Tate Sensorium; see Vi et al.42) to immerse the audience in a multisensory journey, such as walking through a sunflower field. The senses take center stage in forming the essence of the experience, even in the absence of real sunflowers. We call this fusion of carefully crafted sensory elements within specific events to form a desired impression a multisensory experience.40

Now imagine trying to create an impression of an invisible concept, such as dark matter. The idea of dark matter is difficult to understand and has no obvious sensory elements, yet we can use multisensory experiences to communicate this complex scientific concept.37 Both of these examples are enabled through abstracting sensory properties, capitalizing on multisensory perception research, and harnessing multisensory technologies beyond audiovisual interfaces and devices.

Advances within the field of human-computer interaction (HCI) are helping to enrich multisensory experiences through new technologies.13 These experiences are composed of sensory elements that span a technological spectrum—physical, digital, and a blend of both.25 Technology can augment an experience or even serve as its very foundation. For example, you could walk through a field of flowers with your smartphone and use augmented reality (AR) to enrich the experience with detailed information about the different flowers. Or you could be in an office wearing a virtual reality (VR) headset that integrates touch and smell devices to create a fully immersive experience of a field of flowers. The latter is reminiscent of the idea of technology as an experience in itself.23

But immersive technologies such as AR and VR are only one part of merging the human senses with technology into powerful multisensory experiences. Other technologies are adding new layers to this picture, allowing us to target experiences that were never before possible.

Whether the aim is to augment an experience or use the technology as the experience itself, it is important to understand how the senses interact with one another during experiences. As such, concepts from multisensory perception research (for example, sensory congruence) can guide the formation and development of multisensory experiences. For example, when you watch a movie and the sound is dubbed (sound and lip movements do not match), the experience does not feel quite as right as when you see the original, because of visual sensory dominance (see also the McGurk effect). When building multisensory experiences in the context of film that also involve touch and smell (for example, 4DX), one must consider the temporal synchrony of the sensory stimuli to create a harmonic experience.

In this article, we further explore multisensory experiences, diving into each of their four conceptual components, namely impression, event, sensory elements, and receiver.

In the next sections, we first introduce the concept of impression, then shed light on what defines an event and the role of storytelling in multisensory experiences. Next, we explore the integration of sensory elements within specific events, leading to a reflection on the overall story that ties events together to form an impression. We then present the final component of multisensory experiences, the receiver, highlighting its multifaceted nature. After that, we use some examples to explore the interplay between the senses and technology. Finally, we touch upon the responsibilities associated with the formation and realization of multisensory experiences. In other words, crafting and combining sensory elements for desired impressions has ethical implications, from both individual and societal perspectives. This requires researchers and practitioners alike to anticipate, reflect, engage, and act responsibly. We hope this article facilitates a wider discussion about the implications of multisensory experiences in the computing community.

Impressions in Multisensory Experiences

The term impression refers to the perceptual, emotional, and cognitive outcome(s) arising from the presentation of sensory elements in a specific event or series of events.

It starts with sensory elements, which are the raw data presented to the senses (for example, colors, sounds, tastes), leading to sensation, the initial stage of filtering and interpreting this data. From sensation, the process moves on to perception, where the raw data is selected, organized, and interpreted. Perception does not happen in isolation, though; it occurs in close interplay with cognitive and emotional processes.

Those processes can be bottom-up and top-down.24 Bottom-up processing is data-driven and relies primarily on incoming sensory inputs. This contrasts with top-down processing, which is conceptually driven and relies on pre-existing knowledge or expectations. For example, if you are walking down a street and hear a big bang, you instinctively turn around (bottom-up). When you turn around, you realize (top-down) that the sound is coming from a group of youngsters lighting firecrackers.

Perception, emotion, and cognition are interrelated processes that deal with the representation, value, and knowledge associated with sensory information. Together, they influence how an impression forms and the associated responses that follow. (Note, however, that defining such concepts is challenging, as illustrated by Bayne et al.1 in discussing the definition of cognition.) All of these components culminate in an impression, which is the lasting effect or understanding that results from a multisensory experience.

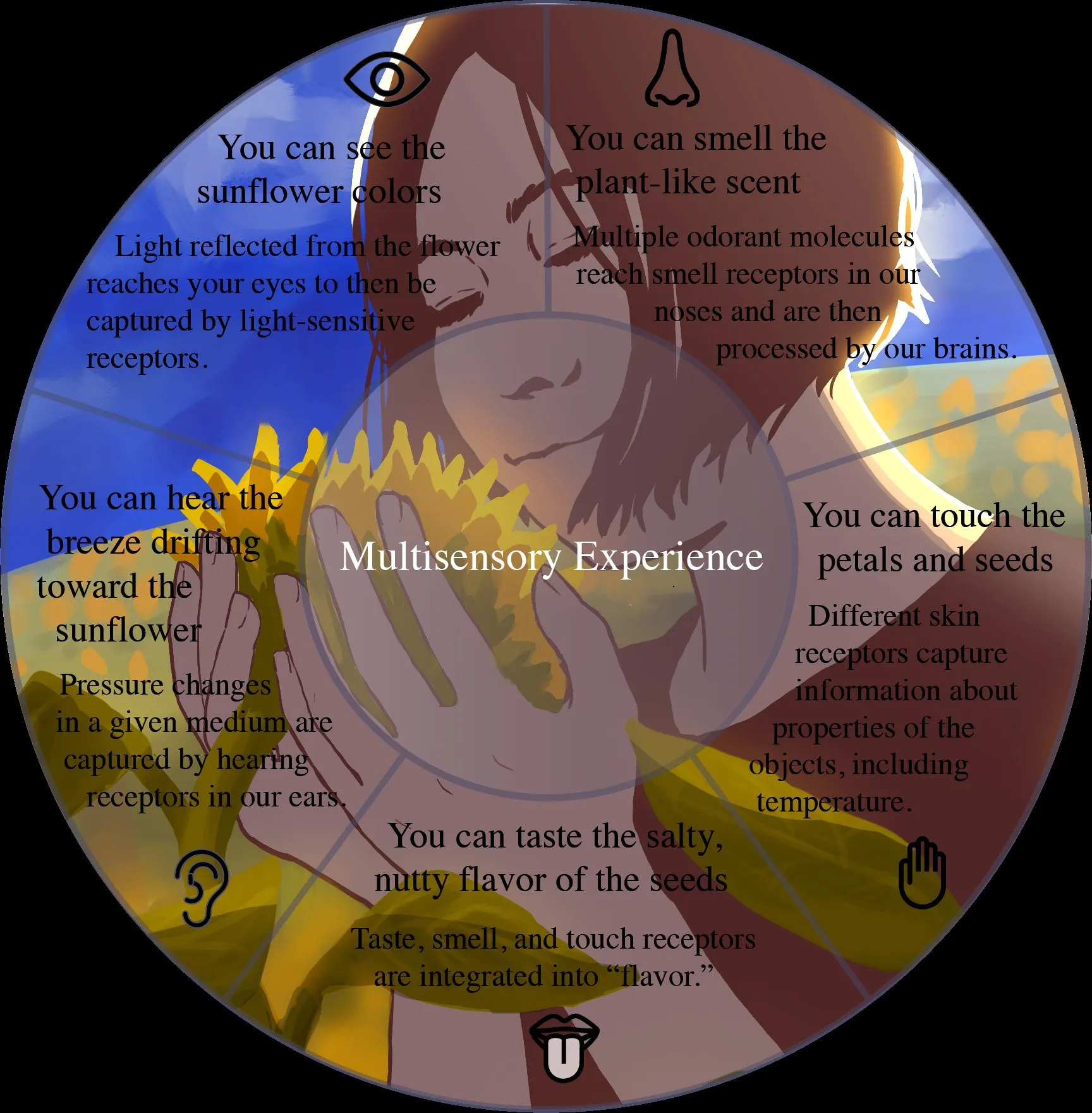

Continuing with our sunflower example, in the presence of a sunflower field, light might be reflected by the sunflowers, reaching the visual receptors in your eyes, triggering the sensation process (Figure 1). Then, through perception, you may initially perceive the vibrant yellow hues and intricate petal patterns. This leads to your appraisal of the sunflower (cognition) and the sense of warmth and awe (emotions) associated with the beauty before you. The sensory characteristics of the flower may catch your attention to begin with (bottom-up) or you might be looking for the most beautiful sunflower, which will determine the way in which your attention is allocated in the sunflower field (top-down).

This example is a simplification of the complexity and interconnectedness of human experiences. Humans continuously process information from the environment to form meaningful interpretations. It is worth noting that various fields, such as computer science/HCI7 and product design,14 have ways of conceptualizing human information processing that parallel what is discussed in this section.

Events in Multisensory Experiences

In this section, we first define events as a key component of multisensory experiences; then, we describe the role of storytelling in creating meaningful sequences of events.

What specific events? In the context of multisensory experiences, there are two viewpoints on the term event. The first, perhaps more narrow view of an event refers to a single encounter. For example, a person may see a rare sunflower for the first time and only on that single occasion. Here, there is only one event to be considered: the encounter with the sunflower. In the second view of an event, however, one may break down any single encounter into different moments in time; for example, the moment you see the sunflower (encounter 1), the moment you pick it (encounter 2), and the moment you put it back (encounter 3).

The experience journey outlined above unfolds over time, involving (at least) a pre, during, and post encounter. This parallels research on customer experience journeys2 and user experience evaluation in HCI.41 If we consider the example of the rare sunflower, even before you see it for the first time, you may go through a series of encounters (for example, seeing a photo, or perhaps a video, of the sunflower or talking with other people about it) that can influence your overall experience. There might also be encounters involving the sunflower after you put it back, which can be critical for the overall experience and memories that you derive from it. In addition, any experience journey you go through can influence the subsequent related journeys you go through.20

To understand the fine granularity of an experience, even a seemingly single event such as the encounter with a sunflower can be broken down into smaller events. Micro-phenomenology, with its focus on the detailed exploration of subjective experiences, allows us to examine the subtle nuances of people’s experiences, helping us uncover the rich temporal (diachronic) and experiential (synchronic) dimensions associated with events.30 This has been demonstrated, for example, in the context of tactile fabric experiences45 and ultrasound-based tactile experiences.29

Using this micro-phenomenological approach, we can emphasize the difference between the two approaches in their concept of events, highlighting the temporal dimension of multisensory experiences. Any given experience can be broken down into encounter stages, where specific sensory elements may play different roles in the formation of the encounter-specific experiences (for example, when you pick the flower), as well as the overall experiences across encounters (from first seeing the flower, to putting it back). This sets the stage for the possibility of creating stories through sequences of events.

What is the role of storytelling? Storytelling in the context of multisensory experiences incorporates narratives along the experience journey. Stories, in a broader sense, are structured narratives with characters, plots, and themes that can shape our impressions and understanding of the world (see Bietti et al.4 and Polletta et al.31 for reviews). Using a more multisensory-focused lens,38 a narrative may be augmented through sensory elements in a series of existing events. Alternatively, sensory elements can be used to create a series of events that make up the narrative.

Following the first perspective, to augment an existing story, sensory elements may be used to, for instance, convey the impact of deforestation (see, for example, TREE VR; https://www.treeofficial.com/). Here, the sensory elements may be used strategically at different moments to anchor the narrative more profoundly in the audience’s mind. For example, the scent of burning wood can evoke an emotional response, enhancing the narrative’s impact on the receiver. In another example, food might be used to augment an existing movie, such as in the case of Edible Cinema (https://www.ediblecinema.co.uk/). This form of storytelling capitalizes on our propensity to form impressions through an existing series of events, thereby reinforcing the narrative through multiple sensory elements (that is, tailored flavor experiences). The temporal dimension becomes crucial, as it allows for the unfolding of the multisensory experience in alignment with the progression of the story.

The second perspective incorporates different sensory elements such as taste, sight, and sound right from the onset of the creative process. The story is not constrained by an existing narrative. For example, in “Silent Flavor,” traditional sound elements in a narrative are replaced with tastes and scents.38 This idea is inspired by the principles of sensory substitution devices,18 technologies designed to convert information from one sense (such as vision) into another (such as hearing or touch). In the silent flavor concept, instead of hearing a scene, the audience would “taste” it, with flavors becoming integral to the storytelling and evolving over time.

Sensory Elements in Multisensory Experiences

In this section, we define sensory elements as key components of multisensory experiences. Then, we describe the relevant concepts underlying sensory integration.

What are the sensory elements? The human senses are typically thought to be vision, hearing, touch, taste, and smell (also known as the Aristotelian senses). There are, however, additional senses such as proprioception, the awareness of body position and movement, and interoception, the sense of the internal state of the body. Each sense can be broken down into sensory elements of varying complexity. These distinctions are important in understanding how we process sensory information. For example, there are low- and high-level sensory elements:39

Low-level sensory elements refer to the elementary features associated with the senses, such as brightness or hue in vision, or pitch in hearing.

High-level sensory elements involve complex recognition and interpretation, such as listening to music, identifying faces, or understanding spoken language.

Sensory elements can be further classified as prothetic or metathetic:36

Prothetic dimensions are quantitative and involve a sense of more or less, such as louder or quieter sounds, or brighter or dimmer lights.

Metathetic dimensions are qualitative (for example, taste qualities such as sweet and sour) and involve different types of experiences, such as different colors or tastes.

What concepts underlie the integrated perception of sensory elements? We typically do not perceive the world from each sense independently. In the context of multisensory integration, the senses are thought to work together to form a cohesive perception of our environment.6 As such, multisensory experiences can draw from several concepts that influence integration (see Velasco and Obrist40 for a detailed overview):

Spatio-temporal congruence: the alignment of sensory elements in time and space9

Semantic congruence: the alignment of sensory elements as a function of a common identity or meaning15

Crossmodal correspondences: the associations that exist between features across the senses35

Sensory dominance: the idea that specific senses might dominate specific stages of the experience journey17

Sensory overload: the idea that too much sensory information in one sense or across senses might overwhelm processing capacity.22

When mixing and matching sensory elements throughout a series of events that compose a desired multisensory experience, the idea is to create the appropriate multisensory ecosystem to increase the likelihood of a desired impression occurring. This ecosystem encompasses all the sensory elements encountered throughout the experience journey. It is not merely the sum of separate instances of sensory elements, but rather a complex, interconnected network where different senses influence and modify each other. For example, the taste of food can be altered by its appearance. Alternatively, if we look at multisensory film as an example, the delivery of foods with specific taste characteristics, such as sour, may be temporally synchronized with the appearance of a new character on screen to surprise the audience, reflecting the fact that sour taste has been described as a surprising experience, or “a firework in the mouth.”28 This integration highlights the temporal and semantic congruence between vision and taste.

The Receiver of Multisensory Experiences

While sour taste as described above might be a surprising experience for many, individual differences in sensory perception have been documented (in, for example, Chuquichambi et al.10). Understanding the multifaceted nature of the receiver of multisensory experiences is therefore key in the formation and realization of those experiences. We need to account for the audience’s characteristics, including their sociocultural and demographic backgrounds, previous experiences, personality, and psychographic and behavioral profiles.

Cultural and demographic elements shape how multisensory experiences are received. Perceptions of specific sensory elements, such as colors, sounds, or aromas, differ across cultures.21 For example, there is early evidence to suggest that European people show more illusion-induced responses to the Müller-Lyer (where two lines of equal length appear different because of arrow-like tails at the ends) and Sander Parallelogram (where the sides of a parallelogram appear to be of different lengths due to the context provided by surrounding angles) illusions compared with non-European samples, likely due to the prevalence of rectangularity in urban environments.33 This suggests that the perception of visual cues (but also cues in other senses) is shaped by one’s environment. Another example, from crossmodal matching tasks, presents intriguing evidence that the Himba people in Namibia associate visual shapes with certain sensory experiences differently from Westerners; for example, they associate carbonation with rounded shapes and match milk chocolate with angular shapes, the opposite of the Western tendency.5

The fragrance of a sunflower might be captivating in one cultural context but not in another. Similarly, factors like age, gender, and socioeconomic status can alter sensory preferences and sensitivities.16 What may be a calming sound to one person or group could be unpleasant or irrelevant to another. Additionally, the influence of personal history and individual traits also shapes responses to sensory elements.10 A certain tune may bring back fond memories for some, while leaving others unaffected. Likewise, personality characteristics, including one’s openness to new experiences (for example, a movie with taste elements) or sensitivity to sensory elements (for example, having a pronounced preference for sweetness), affect how a person perceives these experiences.8

Moreover, the importance of psychographics and behavioral patterns is also critical. Factors like values, attitudes, interests, and lifestyles help in tailoring experiences that deeply connect on a personal level.3 For instance, experiences designed for those who are environmentally aware may focus on naturalistic sensory elements.

These differences across receivers are just a starting point for designing multisensory experiences; depending on the impression that one may want to create, other factors may come into play. What is more, the impression can now be achieved through the interplay between those factors and the technology used to enable multisensory experiences.

Where the Senses Meet Technology

While multisensory experiences have seen growing interest across academia, industry, and the wider public, it is still not the norm to think about them. Furthermore, multisensory technologies are often still limited to audiovisual installations, lacking the meaningful integration of scent, touch, and taste. However, technological advances in sensory devices and interfaces are starting to make a difference (see Cornelio et al.12 for smell and taste interfaces and devices), opening up new possibilities for multisensory experiences. The following two examples illustrate those opportunities. For each, we present the four key components of multisensory experiences described above, as well as the background and enabling technologies.

Multisensory eating in VR.

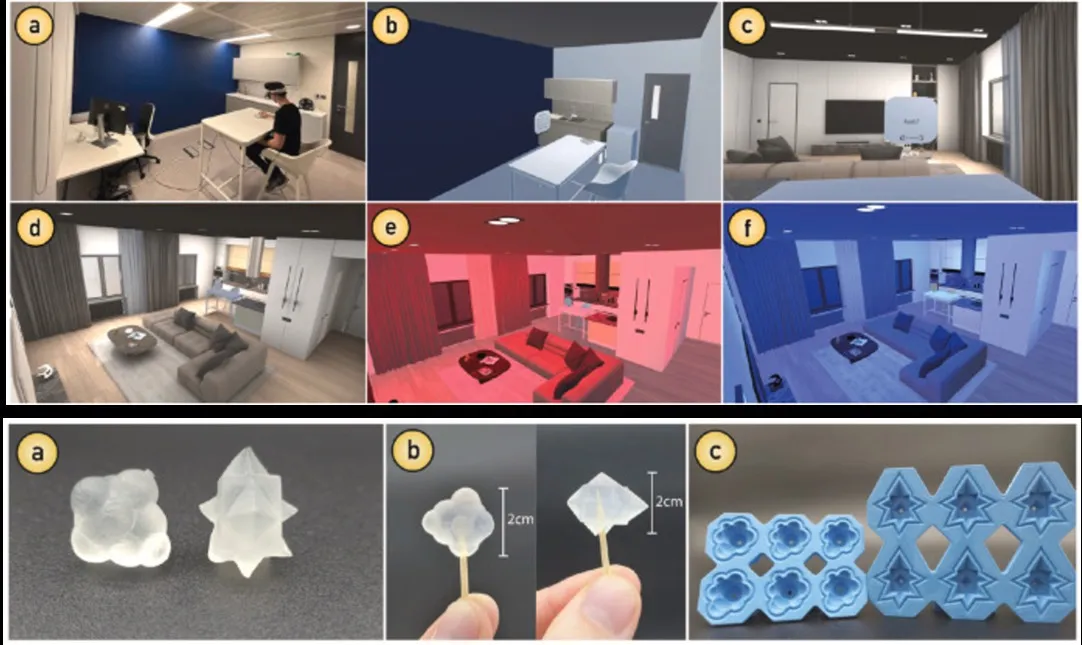

Background and receiver. Food perception is multisensory in nature, involving taste, smell, and touch, though it can also be influenced by any other sensory elements that occur when we eat.32 Here, we present an example of eating in a mixed reality environment where ambient color and food shape in VR are used to enhance specific food experiences based on crossmodal correspondences.11 In this example, the receivers were male and female adults, who were residents of the U.K. and whose first language was English, without color blindness or any sensory impairments affecting taste and smell. This kind of experience is relevant because it demonstrates how multisensory food perception can be enhanced through the use of ambient color and food shape in a VR environment, providing insights into how sensory elements can influence eating experiences. For example, by considering how different senses influence the perceptions of foods and beverages and leveraging this when designing experiences, one might be able to influence sweetness perception and therefore sugar consumption, a major public health concern.44

Impression. The desired impression was to augment sweet taste perception in a VR environment.

Event. The event was a virtual tasting session in a controlled lab environment where different virtual tasting rooms and corresponding light and food shape are manipulated. This example involves a single event—tasting in VR—where an existing story is augmented.

Sensory elements. The key sensory elements are ambient red, neutral, and blue light in VR to enhance the sweet notes of the taste stimulus, which also varies in terms of whether it is round or angular (Figure 2). Through a mix of physical and digital sensory elements, the impression of taste may be modulated, something that is increasingly being explored in food contexts such as restaurants.40

Concepts. Research has shown that, relative to other colors, people associate red, as in this example, but also pink, with sweetness.26 In addition, it has also been suggested that round and angular shapes are associated with sweet and bitter or sour tastes, respectively.10 The concept underlying the experience refers to crossmodal correspondences.

Enabling technology. In physical reality, changing ambiences is challenging and may disrupt the receiver’s experience. In VR, though, we have more control over the sensory parameters of the ambience, therefore opening up the possibility of both conducting multisensory food studies and designing novel food experiences.43

Multisensory dark matter experience.

Background and receiver. The majority of the cosmos is composed of dark matter, a substance that remains unseen and is identifiable only through its influence on gravity. Despite frequent mentions in the mainstream media, the idea of dark matter can be challenging to understand for those without a scientific background. Consequently, there are ongoing initiatives employing innovative technologies, immersive sensory methods, and creative storytelling techniques to demystify the concept. The goal of this science-communication example was to generate a more personal engagement with science, thereby enhancing awareness, enjoyment, curiosity, and the formation of opinions on the complex scientific concept of dark matter.37 In this example, the receivers were museum visitors at the time of the event.

Impression. The intended impression was to help visitors understand the concept of dark matter.

Event. The event took place at a science museum installation on dark matter as part of The Great Exhibition Road Festival 2019. In this example, receivers experience a series of events forming a story in which they metaphorically, yet scientifically accurately, journey through our galaxy. Although not feasible in reality, the adventure is initiated by the consumption of a mysterious pill that transforms receivers into “dark matter detectors.” The concept drew inspiration from the 1999 science fiction movie The Matrix, in which the pill marks the beginning of their extraordinary experience.

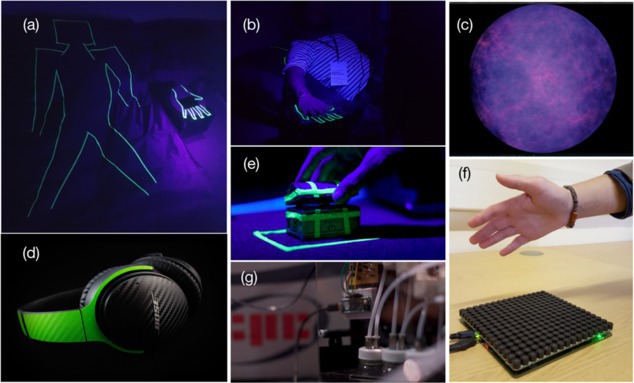

Sensory elements. Receivers step inside an inflatable dome with a friend, lie down on a bean bag, and wear headphones while staring into a simulation of the dark matter distribution in the universe. Key human senses (vision, hearing, touch, smell, and taste) are stimulated throughout the experience (see Figure 3). The user can hear an artificially engineered sound, a storm-like but unfamiliar auditory sensation, that varies in intensity, pitch, and texture to represent the concepts of dark matter wind during an earth-year and its density profile in our galaxy. Black-pepper essential oil, chosen for its unique fresh, cold, and sharp qualities, is dispersed using a specialized scent-delivery system and synchronized with other stimuli to highlight variations in dark matter density throughout the experience. In addition, participants eat an unflavored popping candy that dissolves into a sweet taste and creates a crackling effect inside their mouth and skull, amplified by their headphones.

Concepts. The story ties together a unified understanding of dark matter by aligning various sensory elements in both space and time (spatio-temporal congruence). For instance, sound and haptic feedback (felt as air pressure on one’s palm) are temporally synchronized, enhancing the narrative flow. The experience journey is augmented by the timed diffusion of black pepper scent, leveraging its distinct characteristics to reinforce the impression through sensory integration.

Enabling technology. The exhibit combines various technologies to create an immersive experience. It uses a mid-air haptic device (developed by Ultraleap) to generate touch sensations on the receiver’s hand, a scent-delivery device (developed by OW Smell Made Digital, now known as Hynt Labs Limited) that emits a specific scent at precise times, a projector to visualize the cosmos inside the dome, and noise-canceling headphones to deliver the audio. A central computer system coordinates and synchronizes all sensory elements.

What do the multisensory experience examples teach us?

These two examples illustrate how the senses meet technology to form and realize multisensory experiences, on the reality-virtuality continuum.25 What is unique about the examples is that the “Eating in VR” experience combines a real object—food—with multisensory elements, while the “Dark Matter” experience makes an imperceptible scientific concept perceivable. In both cases, the senses are placed at the center of attention and sensory elements are carefully combined in a virtual or real environment. What sets the second example apart from the first, though, is the integration of storytelling. The audience is taken on a journey through the universe, highlighting the powerful use of sensory elements in creating the impression, and immersing, engaging, and exciting their receivers. With today’s advances in generative AI and AI-powered storytelling, the role of machines in creating multisensory experiences will grow. In this evolution, the focus today is still on audiovisual elements, and to some extent touch (see “Touch the Story” by Sheremetieva et al.34), but smell and taste will eventually mature as well. Will AI help pave the way for advances in chemo-sensory interfaces and multisensory storytelling? The world is certainly not lacking in efforts to develop such interfaces, as summarized by Cornelio et al.12

We argue that today is one of the best moments to design multisensory experiences, in that both science and technology are evolving faster than ever. Nevertheless, when looking from the present into the future, there are still many unanswered questions, especially when the “who” in the design of multisensory experiences is becoming blurred between human and machine. For example, do you want the AI system to decide what you eat, presenting you with the impression you are eating a tasty steak even if it is not? What if technology can augment our senses and enable experiences that not only move us from reality to virtuality but also transform us as humans in an increasingly computerized world? And what ethical considerations must we address when innovating in the context of multisensory experiences? To address the latter question, the responsible innovation framework offers a systematic way to ensure that technological advancements are developed and implemented ethically and sustainably. It focuses on four key dimensions: anticipation, reflexivity, engagement, and action (or anticipate, reflect, engage, and act: AREAa), which we will expand on in the next section.

Conclusions and Responsibilities

The growing degree of integration between humans and technology requires profound reflection on what that means to us as individuals and as a society. We need to anticipate, reflect, engage, and act responsibly. For example, a decade ago, regulations on social media were limited. At the time, we could not foresee the negative impacts that are clear to us now. Looking at the transformation from human-computer interaction to the growing human-computer integration efforts that offer a stronger symbiosis between humans and technology,27 we should not wait for regulations to be put in place. That is, we should begin a debate about the ethical implications and responsible actions that should follow when designing multisensory experiences.

With advances in multisensory technologies, questions arise, such as to what extent are those technologies going to change us as humans? Will they change our everyday lives and become an extension and augmentation of our human capabilities (physical, perceptual, and cognitive)? Further, as we move beyond the audiovisual-dominated design space, inclusivity will be a vital component in designing multisensory experiences. Toward this end, we could even leverage sensory-substitution device principles to transform narrative experiences, allowing audiences to “touch” the stories. Sensory-substitution devices have long been developed for people with sensory impairments in order to transform information from one sense (such as sight) to another (like hearing)—essentially enabling people to “see” through sound (see, for example, Hamilton-Fletcher et al.18). This could not only help pioneer novel ways of emotional engagement that evolve with the narrative, as shown in the “Dark Matter” example, but also ensure that impressions, events, and sensory elements are accessible and appealing to a wide range of individuals, regardless of their abilities, cultural backgrounds, or sensory differences. Inclusive design not only broadens the reach of these experiences but also enriches them, allowing for a more diverse range of perspectives and responses.

The interest in multisensory experiences within both academia and industry signals vast opportunities but comes with significant responsibilities and challenges, notwithstanding the ambitions toward experiential computing that have fascinated the computing community for a long time.19 These challenges encompass concerns such as the digital divide, privacy, security, and equitable access to technology. Addressing these concerns, we have proposed three laws for multisensory experiences, inspired by Asimov’s laws of robotics. These laws aim to ensure that multisensory experiences are beneficial and do not cause harm, treat recipients fairly, and are transparent about their creators and the sensory elements involved.40 The laws serve as ethical guidelines to navigate the why, what, when, how, who, and whom of designing multisensory experiences, stressing the importance of non-harmful, fair, and transparent practices in the formation and realization of these experiences.

Moreover, we propose using the responsible innovation framework AREA in multisensory experiences. Beginning with anticipation, we can analyze potential impacts across economic, social, and environmental realms without seeking definitive predictions. Reflection allows us to prompt researchers and practitioners to consider the underlying motivations, uncertainties, and assumptions of their own work in the multisensory experience space, while engaging with diverse perspectives and addressing societal transformations. Engagement emphasizes inclusive dialogue and deliberation to broaden the discourse surrounding research, innovation, and applications. Finally, the framework encourages action, urging us to leverage insights gained from anticipation, reflection, and engagement to actively shape the direction of the research and innovation process, aligning it with societal needs and desired outcomes. We hope this proposed framework will facilitate a wider discussion about the implications of multisensory experiences in the computing community and beyond. We have now the chance to write and shape the future of multisensory experiences; however, it is not just about creating them, but also doing so in a responsible way.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our supporters, colleagues, and funders for facilitating the research on multisensory experiences, especially the European Research Council (ERC) for supporting Marianna’s research journey under the European Unions Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under Grant No: 638605.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment