Pursuing continuous technology improvement and innovation, organizations of all kinds introduce new systems almost daily, hoping they are adopted by employees, suppliers, customers, and others. From e-reader vendors (such as Amazon and Apple) to insurance companies communicating with their customers through Web applications, the goal is to inspire employees and customers alike to adopt and use new systems. However, despite the best efforts of IS developers, project managers, and trainers, new systems are not always adopted and used as intended. Lacking commitment and constructive feedback from targeted users, IS adoption may simply fail.8,9

Key Insights

- The traditional one-dimensional view of users’ system-adoption behavior, from acceptance to resistance, prompted us to explore a more nuanced two-dimensional view, from “high-use versus non-use” to “support versus resistance.”

- The two-dimensional view highlights inclusion of groups defined by their ambivalent behavior, from “supporting non-users” to “resisting users.”

- Implementers should aim to develop customized strategies to turn potential users into “supporting and high usage” users of new systems.

Here, we explore user behavior toward adopting systems, provide a way to classify users into groups, and suggest strategies for dealing with each such group. Research tends to categorize user behavior in terms of either acceptance3 or resistance,6 a view that fails to acknowledge that such behavior covers a range of ambivalence.12 While people may generally use technology they support, other responses are common as well. For example, Linux workstations have enthusiastic supporters who nevertheless do not use them due to personal or organizational barriers.11 There are also people who routinely yet only grudgingly use Microsoft Office applications. Such behavior—”supporting but no or low usage” and “resisting but high usage”—is ambivalent. Here, we address how implementers can deal with groups showing ambivalent behavior.

Research findings on IS adoption offer little guidance, with researchers focusing on either people’s acceptance by measuring their IS use or use-intentions (such as Ajzen and Fishbein2 and Davis3) or their resistance by measuring their supporting/resisting behaviors (such as Joshi4). In doing so, “acceptance” and “resistance” have, implicitly or explicitly, been conceptualized as an either/or proposition, the opposite ends of a single closed dimension.6 Consequently, user ambivalence remains largely hidden in the literature. Here, we present a case from the Netherlands that highlights two hidden groups of intended users with ambivalent behaviors in adopting an electronic prescription system (EPS) for the country’s general medical practitioners (GPs).

Creating strategies for these ambivalent groups is important, because their behavior is meaningful and differs substantially from groups that are more straightforward in adopting, or not adopting, a system. When supporting non-users are treated as uncooperative mavericks, their initial support for a system could be at risk. And while it seems pragmatic to neglect users’ resistance as long as they continue to use the system, the result could be long-term problems. Finally, the groups with ambivalent behavior can influence others’ reactions toward the system in unforeseen ways. Such influences suggest implementers need customized strategies to cope with the diverse, sometimes ambivalent, reactions of target groups expected to adopt a new system.

We conceptualize IS acceptance and resistance as two dimensions leading to identification of four types of behavior by user groups. Additionally, we identify two other groups that might not use a new system but are involved in its implementation process through their support of or resistance to its adoption. The resulting model consists of six categories IS implementers might subsequently apply to identify and discuss GP behaviors in adopting the EPS in the Netherlands. Finally, we discuss how implementers can monitor and develop customized strategies, particularly for the two “hidden” groups overlooked in the literature: “resisting users” and “supporting non-users.”

Six Actor Groups

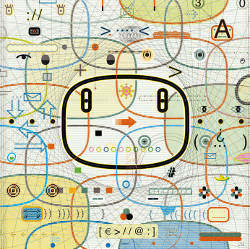

Figure 1 includes four user-based quadrants based on two dimensions derived from the IS-acceptance-and-resistance literature.3,4,6–8,15 The vertical dimension represents interviewed users’ IS acceptance measured by their IS use.3,15 The horizontal dimension represents IS resistance measured through behavioral categories adapted from several organizational behavior theories: Interaction Theory,8 Equity Theory,1,4 and Multilevel Theory of Resistance to Information Technology.7 The degrees apart from no usage to high usage and from resistance to support are continuous, not discrete.

Taking a one-dimensional view of acceptance to resistance, as in the previous literature, non-using supporters would be regarded as either IS supporters or non-acceptors (“no usage”), while frequent-using resistors would probably be regarded as accepting the system despite their grudging use or as complete rejectors in case of aggressive resistance. Implementers may not recognize these two “hidden” groups, viewing them as part of more obvious conventional groups.

Additionally, the figure includes two other groups in the dimension of IS support/resistance. “Other actors” are individuals or groups that can influence and be influenced by IS adoption, even though they are not the intended users.10 For example, management support can influence users’ acceptance or resistance on a particular system, even though managers are not users.6 Due to the fact they are not intended users, these groups are defined by a single dimension covering “supporting” to “resisting.”

Applying the Model

The proposed model can help diagnose intended users’ attitudes, as well as other influential stakeholders’ attitudes toward IS implementation. The dimension covering acceptance to non-acceptance can be determined by individuals’ actual use or by asking about their use intentions. Resistance and support behaviors may be more difficult to trace, especially when passive. Along with alert observation and informal communication, behavioral measurements by means of interviews or surveys represent an effective research tool. Survey questions might include: Do you think using the system will enhance your status or work autonomy? and Do you think using the system will increase your job security? They can be adapted from the literature on resistance toward technology, as in Kappos and Rivard5 and Markus.8

We added two stakeholder reaction types not in the intended user groups but feel they have a stake in the implemented system. Their reactions may be twofold: resist or support adoption and diffusion. For example, patients do not directly use a hospital’s electronic record system, but their support or resistance behavior can influence the system’s overall success or failure because they can agree or disagree with hospital personnel entering their personal information into electronic records. Such behavior may affect a user’s adoption; for example, a doctor may be frustrated with a patient’s resistance and look to work around the system.

Case Study

The case we explore here illustrates how to apply the six-group model to governments looking for ways to deliver decent health care to the public in a cost-efficient way. It covers the Dutch government’s attempt, begun before 2000, ultimately compulsory in 2012, to implement an EPS for GPs to control prescription costs.

Most Dutch citizens turn to a GP when they need non-urgent medical assistance, with GPs running their practices autonomously as independent businesses. A typical consultation with a patient takes about 10 minutes and steps through four sequences: an introduction, with some informal interaction between GP and patient; a health problem explained by the patient; a diagnosis by the GP in medical terms, possibly coded in the International Classification System of Primary Care, or ICSPC; and a decision by the GP as to proposed treatment, including a drug prescription if necessary.

In the Netherlands, the government and/or health-care insurance providers cover the costs of prescribed drugs. Costs vary up to 40%, depending on quantity, type, and brand. Initial studies had calculated that total annual cost savings would be 20%, or about 136 million Euros, if all Dutch GPs would issue consistent, cost-efficient prescriptions. The government’s Ministry of Health Welfare and Sport worked with the country’s health insurers and College of General Practitioners and a software company to develop a reliable, user-friendly EPS; the College of General Practitioners negotiated financial benefits for its members in exchange for their cooperation.

Using the EPS to determine appropriate treatment when consulting patients, GPs input their own diagnosis, a list of available drugs, and the patient’s personal and medical data. The EPS database includes current drugs, past drugs, drug allergies, drug interactions, and drug costs. The EPS accounts for a patient’s specific situation when recommending a treatment, accessing the data when the GP enters the patient’s number and diagnosis code from the ICSPC coding system. GPs can then use the EPS to print out and/or email the prescription directly to a pharmacy.

The EPS is designed to advise GPs as to the “best” treatment for a given diagnosis based on the patient’s prescription needs, quantity, and most cost-effective brand of medication. The targeted savings were considered feasible if 90% of the country’s GPs would adopt the system and follow the recommended treatments in more than 80% of their cases.

To make the system as widely available as possible, the Ministry initiated a large-scale implementation campaign, including instruction videos, booklets, and posters, aiming to educate the country’s 8,200 GPs as to how to install and use the system.

Six months following implementation, approximately 50% of surveyed GPs had installed the system, with 50% of this group consulting it at least once a day. However, consulting the system does not necessarily mean a GP would follow its recommendations.

Data was based on our observation of GPs using the system; interviewing 50 of them, along with eight other actors from the implementation team, the Ministry, and health-insurance companies, and reviewing the relevant implementation plans, user manuals, and evaluation studies. We then categorized the interviewed GPs and other relevant stakeholders according to our model (see Figure 2).

Resisting but high usage. Resisting-but-high-usage GPs perceived problems and disadvantages but still used the system (ambivalent behavior). Some were required to do so by their group-practice managers or colleagues. Typically, they used the system but did not follow its recommendations for several reasons: lack of trust in the recommendations; disagreement with recommended quantity or quality of drugs; or limiting access to obtaining a second opinion after a patient had left the consultation room. The two groups in this quadrant were the 18% of the 50 interviewed GPs who used the system to obtain a second opinion and the 20% who did not trust or agree with the system’s recommendations. These groups differed in that GPs from the 18% group used the system to gain confidence determining their patients’ prescriptions, though such use did not coincide with the Ministry’s publicly stated intentions.

Supporting and high usage. Only 12% of the 50 interviewed GPs said the EPS was easy to use and useful in producing quality output when consulting patients. These supporting-and-high-usage GPs said the system saved them time so they could focus more on the consulting process itself, making consultation more efficient. For example, rather than abruptly conclude a 10-minute consultation with a patient, they could suggest the session was about to end by inserting a special code into the system. These GPs emphasized their prescriptions had become more consistent with those of their colleagues. The result was less time and money spent per patient in group practices and by GPs working part time, as well as by better management of patients’ medical data and archives.

Supporting but no/low usage. Among GPs with this ambivalent behavior, 14% openly acknowledged the system’s usefulness but said they did not use it due to practical, system-related reasons. Some said they were simply too busy to install it on their computers. Others said they welcomed the idea of using it but lacked the ability or experience to handle the ICSPC coding system that was a prerequisite for use. Yet others deliberately did not have a computer in their consulting rooms to create, they said, a quiet, patient-centered atmosphere but also said they appreciated the idea of a computerized prescription system.

Resisting-and-no/low-usage. Among the 50 interviewed GPs, 36% belonged to the quadrant labeled “resisting and no/low usage.” Some viewed the system as complicated, inflexible, and not always available, and consequently felt it would take away from their consultation time with patients—the most medically significant reason indicated for not using the system. Others felt it disrupted their brief contact with patients because they were communicating with the system, not with the patients. In particular, when they had external visits (outside their offices), they did not take a computer with them. Another reason for rejection was financial; to adopt the EPS, they would have had to update or change their computer networks and purchase and implement a new or modified system of patient records. For them, adopting the EPS was simply an additional expense. They also tended to view the EPS as a threat to their social status, feeling politicians and insurers were using it to increase control over their medical practices and weaken their medical autonomy. Other GPs in the same category feared the system would weaken the perception of therapeutic aura or respect traditionally bestowed on physicians. This could lower the esteem given them by the patients for whom a prescription drug might work as a placebo. Finally, some GPs were concerned about a cultural change in their practices due to innovation, their own initiative, and experimentation to mere compliance with external standards imposed by government administrators.

Resisting and supporting groups. The Ministry and the insurance companies strongly encouraged GPs to adopt and use the system. The College of General Practitioners was supportive though less strongly than other groups. The representative group of patients interviewed shared the GPs’ concerns about the system, while other stakeholder groups did not strongly resist EPS diffusion.

This case study illustrates how we could have misunderstood 52% of the GPs interviewed if we had taken a one-dimensional view—acceptance versus resistance. Moreover, two groups within the quadrant labeled “resisting but high usage” showed user reactions are a matter of degree. Implementers should take this into account when developing their strategies.

Promoting Adoption

Here, we assume IS implementers aim to move all users into the supporting-and-high-usage group. In discussing strategies, we focus on the two groups of interviewed GPs with ambivalent behaviors: “resisting but high usage” and “supporting but no/low usage” (see Figure 3):

Resisting but high usage. This ambivalent behavior deserves attention because it is part of an organization’s shadow system, with significant influence on overall organizational performance. Though users showing this behavior are considered high usage, it is likely they are forced to use the system, as with 20% of the GPs. In other cases, some people might use a system because they opportunistically experience it as the most convenient option, as 18% of the GPs said they did. These two groups should be treated differently. Users from the 20% group were usually experienced older GPs participating in group practices who felt using the system would go against professional norms valuing personal relationships with patients. They also feared losing autonomy as traditional doctors. Moreover, their concerns were ignored, even as they felt managerial or peer pressure to use the system. To address these concerns, we suggest the following:

Cultural resistance. Potential users can view a system as incompatible with their personal or organizational norms and values. Implementers should thus engage in a dialogue with them to understand those values, explain how the system does not violate them, and cooperate in modifying the system to uphold them; and

Fear of losing autonomy. Implementers should determine whether concerns about losing autonomy are substantial and legitimate or unfounded. If legitimate, the implementers should negotiate with potential users to achieve a win-win scenario through compensation and other methods. If unfounded, the implementers should do their best to reassure the users they have nothing to fear.

The interviewed GPs from the 18% group were predominantly less-experienced young doctors participating in group practices, feeling under-informed about the consequences of adopting the system, so used it conservatively to obtain a second opinion:

Uncertainty. Anyone can fear and resist a system when ignorant of the consequences of its use. Implementers should explain its purpose and implementation process so the intended users anticipate the changes likely to occur.

Supporting and high usage. Retaining “supporting and high usage” users is as important as attracting users from other groups. Implementers can gather, analyze, and apply the reasons to retain users in this group and attract others from other groups. For example, many young urban GPs from group practices were in this category, believing their use of the EPS made them more professional while increasing medical quality and consistency. Implementers can encourage users in such a group to be advocates by, say, inviting the supporting-and-high-usage GPs to discuss and share their positive experience with the passively resisting-but-high-usage GPs using the system only to obtain a second opinion.

Supporting but no/low usage. Implementers should beware of viewing this ambivalent group as resisting users just because they do not use the system. Through a mechanism of self-fulfilling prophecy, this group can easily turn into hardened system opponents. Managers and other implementers should explicitly recognize their support and reward it by helping them detect and minimize any related obstacle they may face.

Here, both people- and system-oriented interventions8 may help:

Materializing support. Implementers can inquire about the technological and practical issues confronting users. The supporting-but-no/low-usage GPs were eager to report their difficulties adopting the system when we interviewed them. Implementers should acknowledge potential users who willingly provide such constructive feedback, telling them how and when the system will be improved to reinforce their promise to use the system.

Technical barriers. People often do not use a system due to lack of skills and/or knowledge. For example, implementers could help the GPs who said they did not know how to use the ICSPC coding system, offering a course through, say, the GPs’ own professional association, accrediting it as credit points health professionals must earn annually to maintain their licenses.

High sunk14 or switching costs.13 People locked into a particular system find it difficult to switch to any other system. Many of the 50 interviewed GPs reported they could not use the EPS due to incompatibilities with their current computers and networks. Implementers mitigate these barriers by providing extra support to upgrade equipment, including grants and tax deductions.

Resisting and no/low usage. The largest percentage of interviewed GPs (36%) was in this quadrant, mostly experienced doctors practicing independently in small towns who valued their close relationships with their patients, usually knowing them by first name. Moving actors in this quadrant to the desired behavior is especially challenging.

Though implementers try to rationally convince users to adopt supporting-and-high-usage behavior, such an approach may also bring unintended side effects for GPs, in light of their values and limited resources.

Rather than move potential users directly to the “supporting and high” group, implementers should first try to move them to the “supporting but no/low usage” group by following the recommendations outlined earlier in the section on “resisting but high usage.” One is to organize open discussions between “resisting and no/low usage” and “supporting and high usage” GPs as to whether the EPS reinforces their values in suggesting more effective drugs for patients. One drawback is the process takes time, even before a GP would start to use the system.

Under some circumstances, implementers can guide potential users toward “resisting but high usage” by forcing them to use the system, as was tried by some managers of GP practices. For independent GPs in small towns, the government could try administrative or financial incentives or even legal means, though the latter would likely provoke even stronger resistance. Therefore, implementers must be prepared to address users’ resistance swiftly and sincerely; otherwise, they will fester, eventually hurting overall organizational or professional performance.

Resisting and supporting groups. Much literature, including Kappos and Rivard,5 Lapointe and Rivard,7 and Mitchell et al.,10 has covered how to support other actors (such as through coalitions) and resisting other actors (such as through mutual benefits and common goals). The effort by the government, insurance companies, and College of General Practitioners to win support for the EPS throughout the Netherlands shows IS diffusion does not mean simply providing a technological solution. At times, implementers must mediate political conflicts or acknowledge and address users’ emotions concerning the system.

Conclusion

The model introduced here defines ambivalent adoption behavior and explores their occurrence in a real-world context. Moving intended users from low to high use involves system-related support; moving intended users and other actors from resistance to support involves a wider context (such as power shifts, feelings of insecurity, and working environments). These ideas shed light on a gray area previously ignored in the literature on system acceptance and resistance, contributing a new perspective on IS adoption and helping practitioners work with ambivalent groups. We invite researchers to specify the antecedents of ambivalent adoption behavior, as well as the conditions under which intended users might move from quadrant to quadrant. Interaction among the six different groups is another promising area for research.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment