It was approximately five years ago, during a Zoom call with central bankers, when some of us became aware of the glaring importance of digital trade.a

In principle, countries should be able to capture digital trade through their systems of national accounts. But in practice, as some of these colleagues mentioned, digital trade was a different beast. It is deployed by networks of multinational firms optimized for tax purposes. Networks collecting revenues in countries different from those in which these digital products are being made or delivered. Their intuition was that much of this trade was not being captured, or at least, not being captured well in their system of national accounts. They were concerned about a gap in the data, but didn’t have a good guess about how big that gap was.

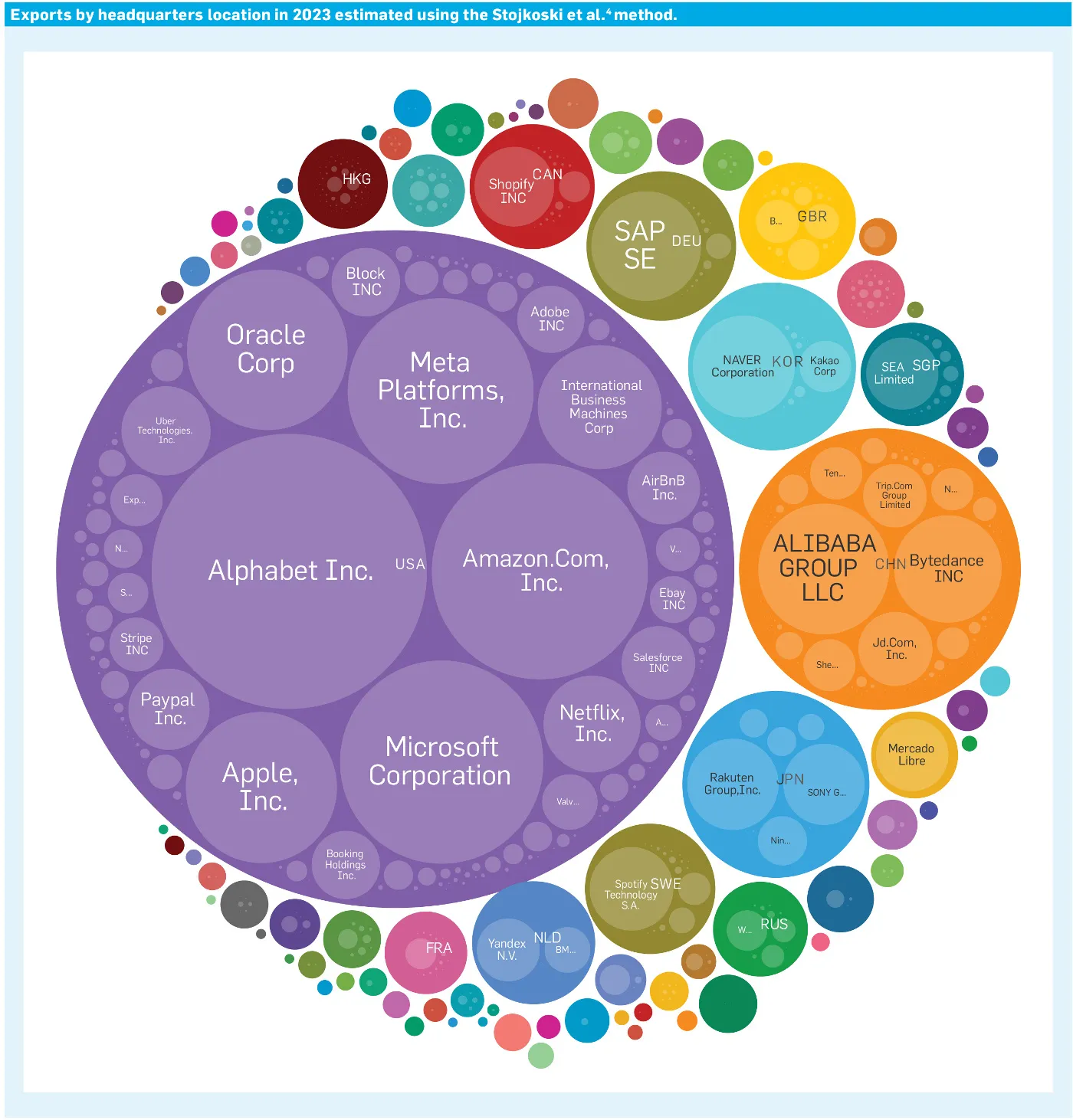

So, for the next couple years, we collected data on corporate revenues and digital consumption to build a machine learning model that we could use to estimate the trade moving through routers instead of containers. Trade involving everything from cloud computing and mobile games to food delivery and dating apps. Our results, which were published last year in Nature Communications,4 showed that digital trade was indeed a different beast. It was not only substantial, approximately one trillion dollars in 2021, but growing much faster than others forms of trade (at an annualized rate of 24.5% between 2016 and 2021). It was a new engine of economic growth with a partly invisible global reach.

In 2025, we care about digital trade because it is large enough to alter our notion of trade balances. In economic terms, digital trade satisfies the cliché of being the new oil, since the world is trading about the same in digital products than in crude petroleum (which in 2023 amounted to U.S. $1.28 trillion). In the case of the U.S., the largest net exporter of digital products, we estimate a trade surplus of approximately U.S. $600 billion,b which is comparable with all of the physical product exports of France, the seventh largest exporter in the world. (See the accompanying figure.)

As our central bank colleagues feared, this surplus seems partly unaccounted for in balance of payments data. Trade through commercial presence abroad (what is known formally as “GATS mode 3 trade”) is inherently difficult to measure. There is a reason why the IRS and Meta have been battling over a decade for assets that Meta reports in Ireland.3 This means our estimates are complementary to these published1,2 in a joint effort by the OECD, IMF, UNCTAD, and WTO, which put the “digitally delivered services exports” of the U.S. at U.S. $649 billion and attributes only U.S. $49.7 billion to “computer services.” By using corporate revenue data, we extend this categorical resolution to 31 sectors while helping reconcile the numbers with the fact that many of these companies have revenues that are north of $100 billion and that do not come solely from their operations in the U.S.

But even when disaggregated into nuanced categories digital trade can be large. We estimate U.S. exports in digital advertising and cloud computing to be, respectively, approximately $260 billion and $184 billion. Compare that to the exports of aircraft and integrated circuits, which in 2024 were respectively, $123 billion and $50 billion. That makes the U.S. an exporter of bits rather than of atoms. Recent technological advances such as generative AI will likely tilt the balance even more towards digital exports.

We all understand that Silicon Valley is an export hub focused on products that are consumed globally. From the perspective of economic theory, there is nothing surprising about this. Countries should export the things they are better at. But digital trade behaves differently. Today, with the exception of a few countries such as the U.S., China, and Uruguay, most countries are net digital importers, selling atoms and importing bits. When digital trade is poorly accounted for, this distorts trade balance estimates and their policy implications. Trying to balance the visible trade of products while ignoring digital trade might lead to false conclusions.c

Consider the case of Vietnam, a rising footwear and electronics manufacturing powerhouse. Vietnam’s spectacular physical trade surplus with the U.S. (~$100 billion in 2023) has helped the digitalization of its population, and consequently, their ability to import digital products. Taxing Vietnamese-made rubber sneakers, which are unlikely to be manufactured at similar prices or numbers in Mexico or America, would cut the ability of Vietnamese workers to pay for American digital products, such as YouTube or Instagram ads. Trade is win-win, but you must let it flow.

Certainly, these issues do not only concern digital exports. Other service exports also suffer from similar mismeasurement problems. It is difficult to estimate how much of the revenues generated by a McDonald’s in France are due to marketing activities originating in the United States. But digital trade is different. It is unlikely to demand as much local labor as a service like McDonald’s, making it a more direct export.

The rise of digital trade is reshaping global commerce. As the U.S. and a handful of other nations export vast quantities of digital goods—from cloud computing to advertising—the old calculus of trade imbalances in products and services may no longer tell the full story. The unaccounted surplus in digital trade not only underscores the growing dominance of intangible exports but also highlights the risks of misaligned policies. Countries should work to update their national accounting practices to better capture these forms of trade, and digital trade should be featured more prominently in the agenda of international trade negotiations.

Attempting to “fix” trade deficits in physical goods while overlooking digital flows could disrupt a symbiotic exchange. The challenge for researchers is to study this new reality. The challenge for policymakers is to recognize it, ensuring trade frameworks evolve alongside the invisible engines of the digital economy.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment