We are pleased to have this opportunity to address questions raised by ACM member William Bowman1 with respect to the ACM’s financial reserves. The Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) is a professional society governed by its volunteer leadership.2 At all levels of volunteers and staff, we are committed to serving ACM members and, together, advancing the field of computing as a science and a profession globally. Part of that commitment involves careful listening, consideration, and action as it relates to issues of importance to our members and the future of our organization.

In his opinion piece, Bowman raises questions about the ACM’s financial reserves and how those funds are and should be used. We recognize that other members may share Bowman’s questions, and we believe it is important to address them in a public forum. By directly and transparently addressing some of Bowman’s points and any misconceptions about the ACM’s operating model, we are confident we can create a better understanding of and appreciation for the importance of the ACM’s financial reserves.

Why the ACM’s Reserves Are Essential

Bowman states that nonprofit organizations should not be profitable, and that the ACM is not serving its mission by maintaining its currently high financial reserves. On the contrary, we believe these reserves are crucial for sustaining activities that support our mission and cover the organization’s many commitments. Such reserves are consistent with well-functioning nonprofit organizations.4 Most notably, our current reserves make possible the ACM’s transition to a fully open DL.

By January 1, 2026, we aim to make the ACM’s DL fully open, providing free access to everyone, including members, the global computing community, and anyone interested in the field. This important initiative aligns perfectly with our mission of fostering the open interchange of information, but substantial financial resources will be required to make this happen. As we will discuss throughout the remainder of this response, the ACM will be using its current reserves to provide this service to the community.

A point of clarity: The terms “profit” and “loss” used throughout Bowman’s article pertain to for-profit organizations. The correct and legally meaningful terms for nonprofits are “surplus” and “deficit.”5 Nonprofits, such as the ACM, reinvest surpluses to support the organization’s mission and long-term viability.

What Are the Sources of the ACM’s Surplus?

A central question in Bowman’s article is about the source of the ACM’s surplus in the annually filed 990 forms he examined. Bowman also used information from the ACM Publications/Digital Library (DL) financial report.6 As he notes, the answer to his question cannot be determined by examining only the 990 forms because IRS categorizations differ from how the ACM operationally addresses revenue and expenses. For example, while the IRS has salaries as a single category, in terms of the ACM budgeting, staff salaries are allocated based on the programs to which they contribute.

We address Bowman’s question from a full ACM operations standpoint. The sources that Bowman considers might contribute to the ACM surplus are:

Conferences: From the 990 forms, it appears that conferences do not generate a surplus. However, there is funding for conferences from sources other than registration fees that comprise the 990 forms information. These other sources include sponsorships and donations that are listed separately in the 990 forms. Historically, conference surplus accounts for as much as 50% of the annual total surplus.

Investments: Under the direction of the ACM’s volunteer Investment Committees over the years, the ACM’s investments have done well. Unrealized gains from investments are not included in the 990 forms, so they would not contribute to any surplus. However, interest and dividends would. On average, the interest and dividends are approximately 30% of the annual surplus and are allocated to various restricted funds and the special interest groups (SIG)s. Depending on the financial markets, this varies from $1.8M to $3.5M each year.

Advertising: Advertising revenues also contribute to the ACM’s surplus. This revenue stream, however, has decreased since 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic occurred.

ACM DL: For publication and DL finances, we can look to information published in Communications of the ACM about Publications/DL finances. As summarized,6 historically, a 3% to 5% surplus was generated each year through DL revenue, but in the calendar year 2022, this changed to a deficit of 1%. This deficit is explained by several factors, such as an increased number of publications, backlog on several publications resulting in additional issues, global inflation post-COVID, and investments in the future of the ACM DL, including platform enhancements and new publications.

Membership dues: Bowman mentions the revenue from membership dues, suggesting that these dues may be too high and may be contributing to the ACM’s surplus. However, for these dues, members receive benefits. Examples of products and services for members include a print version of Communications of the ACM, books, and courses. ACM professional dues also help to subsidize memberships for students and for individuals from economically developing nations. Dues do not account for any of the surplus.

In sum, to answer Bowman’s question about the source of the ACM’s surplus, the sources that contribute are conferences, investment returns, and advertising revenue. Publications/DL has historically contributed but did not contribute last year.

Preparing for What’s Next: Opening the ACM’s Digital Library

To attain a financially sustainable, fully open DL, ACM leadership has worked for the past four years on transitioning from the paywalled DL to a fully open DL through the ACM Open1 model. With ACM Open, the DL will change from a pay-to-read financial model to a pay-to-publish financial model based on licensing agreements with institutions, such as universities and research institutes, to fund publishing for their employees and students.

Under current projections, the ACM anticipates recovering only 70% of the income from these institutions that was generated through the previous pay-to-read model. Some additional revenue will come through Article Processing Charges (APCs) for authors who are not associated with an ACM Open institution and do not otherwise qualify for a fee waiver. However, even with APCs, we still project a shortfall in the revenue required to pay the costs of the DL.

While significant progress has been made with the institutional support of the ACM Open model, the full realization of a sustainable DL still carries many risks, such as lost DL subscription revenue, as well as conferences and authors leaving the ACM to avoid APCs.

ACM leadership is closely monitoring the progress of the transition to a fully open DL. In terms of DL subscription revenue alone, the ACM is projecting a loss of $6M to $8M in 2026 when the DL goes fully open. The five-year projection is for a loss of $25M to $30M.

The potential revenue loss from the other sources mentioned above has not been fully modeled. It will likely be a few years before these impacts are understood well enough to adjust for the annual losses. Without knowing that the ACM had sufficient reserves to operate the organization despite what could be large revenue reductions, it would have been irresponsible for ACM leadership to invest in major initiatives like the open DL.

Without knowing that the ACM had sufficient reserves to operate despite what could be large revenue reductions, it would have been irresponsible for ACM leadership to invest in major initiatives like the open DL.

Bowman suggests the ACM should be spending down cash reserves. With the transition to a fully open DL, there is no need to explore ways of doing this as such spending down will be happening.

The ACM’s Restricted Funds

Paying for a nonprofit organization’s day-to-day operations requires some unrestricted funds. These funds need to be large enough to cover operations and commitments for the future.

In addition to unrestricted funds, nonprofits typically also have restricted funds, which cannot be spent other than for their designated purposes. Examples of restricted funds for the ACM include:

Awards Fund: Funding for ACM Awards provided by industry and by allocations from ACM surplus

SIG Fund: Funding restricted for SIG usage provided by surpluses from SIG conferences and other activities

Conference Fund: Funding for new projects of non-SIG ACM conferences provided by surpluses from these conferences

Development Fund: Start-up funds for new ACM volunteer activities provided by allocations from ACM surplus

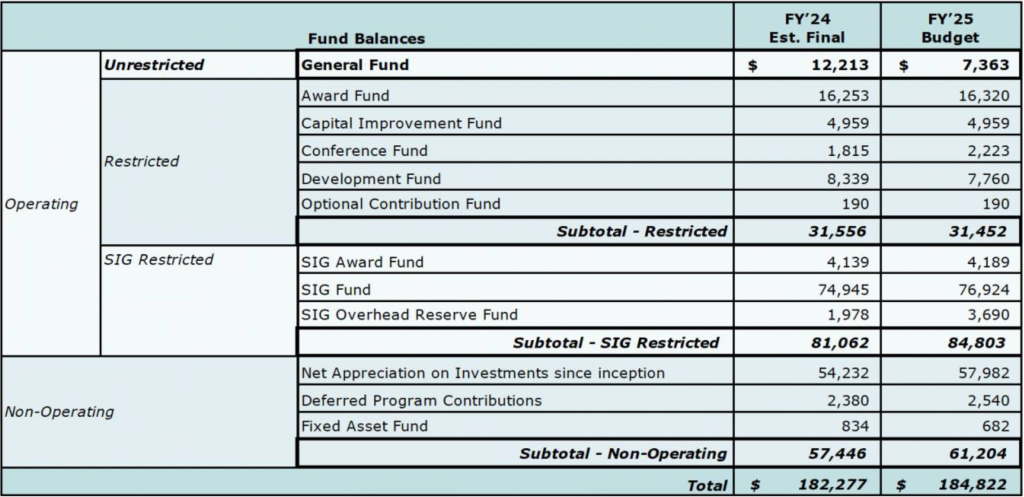

The Table provides a look at the ACM’s restricted funds for the 2024 and 2025 fiscal years.

There are some critical points to note from this Table. First, for fiscal years 2024 and 2025, most of the ACM’s funds are restricted. The General Fund is the sole unrestricted portion of the ACM’s operating funds and accounts for only 10.9% and 6.3% of the ACM’s total operating funds for FY’24 and FY’25, respectively. It needs to be further highlighted that the General Fund is expected to decline in FY’25 for the first time in many years.

Critically, the non-operating balance consists of funds that cannot be spent down. These non-operating funds are the following:

The net appreciation on non-operating fund investments includes the unrealized gains from ACM investments.

The ACM’s treatment of deferred revenue follows ASC 606 for accrual accounting, which requires that revenue be earned when services are rendered rather than when cash is received. Revenue such as prepaid annual membership fees illustrates revenue that is deferred until earned when the service is provided. The Table shows the ACM’s deferred assets as non-operating expenses because the ACM is not allowed to use these funds until the service is rendered.

The Fixed Asset Fund represents non-operating expenses such as equipment.

Comparison to Peer Organizations

Bowman suggests comparing the ACM’s finances with those of other organizations, such as arXiv. He indicates that arXiv has only about six months of operating costs in reserve, which he suggests is common for nonprofits.

To answer the question of optimal reserves for nonprofits, it is important to understand that professional societies are not all the same with respect to the scope of activity and the associated financial requirements. arXiv differs significantly from the ACM, having very different financial needs and risk exposures. Funded by Cornell University, foundations, and university contributions, arXiv is solely a digital library. It does not have a mission that is comparable in scope to the ACM, which includes conferences, educational curricula, public policy, professional ethics, and so on.

Rather than comparing the ACM to arXiv, it is more useful to compare the ACM’s financial reserves to peer professional societies that run publications, conferences, and other member-facing programs. For the year 2022, we compared the ACM to four peer societies: AAAI, AAAS, ACS (the American Chemical Society), and IEEE, based on data from publicly available 990 forms.

In doing this comparison, it is important to look not only at the funds the organization has but also to consider how much of those funds are restricted and how large the organization’s commitments might be. To consider these factors, we looked at the ratio of the sum of cash plus investments to commitments for the ACM and peer professional societies. This ratio indicates the degree to which an organization has enough resources to meet its commitments. With a ratio of 1.00, the organization only has enough cash and investments to meet its commitments with no funds to spare. Ratios higher than 1.5 are deemed to be healthy. For the ACM, this ratio is 3.628. Compare this to the ratio of the four peer organizations examined: 5.437 (AAAI), 2.525 (AAAS), 4.165 (ACS), and 3.995 (IEEE). ACM is squarely in the range that other large, multifaceted nonprofit professional societies deem necessary to meet their commitments and keep the organization viable for the foreseeable future.

ACM is squarely in the range that other large, multifaceted nonprofit professional societies deem necessary to meet their commitments and keep the organization viable for the foreseeable future.

Encouraging ACM Member Involvement

Bowman suggests that members need to get involved. We agree and encourage all members to get involved through voting, volunteering, and engaging in ACM activities. The ACM is its membership and the larger global computing community that is served by member engagement.

In Closing

The ACM’s financial reserves are not only a testament to prudent management but are also essential for our ability to fulfill our mission. By maintaining these reserves, we ensure that the ACM can continue to support its diverse and valuable programs, adapt to new challenges, and invest in major initiatives like the open DL. Should you have further questions, we welcome an open dialogue. Please reach out to us at questions@acm.org.

In the meantime, we strongly encourage our members to remain engaged and involved in the ACM’s activities. Your participation and feedback are crucial as we navigate these transitions and continue to work toward our shared goals. Together, we can ensure that the ACM remains a robust and effective organization, capable of meeting the needs of the computing community both now and in the future.

We thank you for your ongoing support and dedication to the tremendous results we achieve together.

Acknowledgment

We thank John West, ACM’s Secretary-Treasurer, for his insights related to financial information and the ACM’s financial future reported here. We also thank other ACM staff, volunteers, and reviewers who provided their insights about issues discussed in this article.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment