Should European press publishers be granted a new intellectual property (IP) right over online uses of their journalistic contents? These publishers have long had both copyright and sui generis database IP protections for these contents. Yet the European Commission, Council, and Parliament have been convinced that only by granting the new IP right will sustainable quality journalism continue to be produced in the EU. Despite some strong opposition, this proposal seems likely to be adopted and made a mandatory part of EU law.

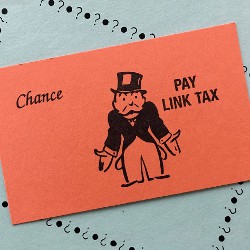

Sometimes known by its critics as the "link tax" provision, Article 11 of the proposed Directive for the Digital Single Market (DSM) would grant press publishers a new set of exclusive rights to control the reproduction and making available of online journalistic contents by information society service providers. Under the proposed compromise text made public in November 2018, these rights would last for one year.

Critics of Article 11 have tried to blunt somewhat the scope of this new right. For instance, the Parliament’s version of Article 11 would provide that the right "shall not extend to mere hyperlinks which are accompanied by individual words." But the Council and the Commission have not exactly agreed to this change or to the Parliament’s proposed exception for "legitimate private and noncommercial uses" by individual users; negotiations to finalize the text of this Directive are ongoing and likely to be concluded in 2019.

Arguments for the Press Publisher Right

It is no secret that these are trying times for press publishers. Paid subscriptions have generally declined, readership has eroded, and advertising revenues that long supported print journalism have shrunk. The transition to digital publishing has been challenging and required experimentation with new business models. Press publishers are fearful these business models will not suffice to sustain their industry.

The moral argument said to support the new press publishers’ right arises from a sense of unfairness that technology companies (think Google) and online news aggregator services (for example, Meltwater) are making money, either from advertising or from subscriptions, by providing members of the public with free access to their news, through links and snippets, without compensating the publishers who provided that news.

A secondary argument has focused on difficulties that press publishers have sometimes encountered in proving copyright ownership in articles written by freelancers when suing search engines or news aggregators.

Some momentum for the press publisher right has built up in the last few years, taking advantage of a general sense of hostility in the EU toward major technology U.S. companies. Google, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon (aka GAFA) are chief among them.

Complaints are legion that these firms have abused their dominant positions, been responsible for fake news and privacy breaches, and/or shown indifference toward other firms’ IP rights. EU policymakers have been persuaded that there is a "value gap" that digital technology companies should fill by licensing content from EU press publishers, among others.

Lessons from Germany and Spain

A few years before the DSM Directive was proposed, press publishers persuaded the German and Spanish legislatures (in 2013 and 2014 respectively) to pass laws granting them rights similar to those that Article 11 would mandate for all EU member states. These laws have met with much less success than their proponents had hoped.

After the German law passed, press publishers authorized VG Media, their collecting society, to establish 6% of gross revenues as the license fee it should collect from technology firms for rights to make online uses of the publishers’ journalistic contents. According to a report commissioned by a European Parliament committee (whose lead author is the well-known copyright scholar Lionel Bently), Google refused to pay such a fee and eventually got some free licenses.1

These licenses notwithstanding, VG Media sued Google for violating this right. A German court stayed the proceedings so that the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) could address a question about the validity of the law. As of 2017, the society had issued only five licenses and collected a total of 714,000 euros.

Google also refused to pay license fees to contents of Spanish press publishers. Instead it shut down its Spanish Google News service. Seemingly as a result, estimated traffic to Spanish news sites declined by somewhere between 6% and 30%. Search engines and news aggregators, it turned out, had driven traffic to Spanish news sites. Very few licenses have issued under the Spanish law.

Why Many Oppose the Proposed New IP Right

In April 2018, a group of 169 IP academics sent a statement to the EU Parliament strongly opposing Article 11.4 There was, it said, "no indication whatsoever that the proposed right will produce the positive results it is supposed to." Moreover, "considering the current high levels of market concentration on online advertising markets and in media, a publishers’ right may well backfire: further strengthening the power of media conglomerates and of global platforms to the detriment of smaller players." (By July 2018, another 69 IP academics joined this letter.)

Article 11 would, the Statement concluded, impede the free flow of news and other information vital to a democratic society, harm journalists who often rely on search engines and aggregators, and create uncertainty about its coverage and scope.

It was also unclear how the new publisher right would interact with existing copyright laws, which typically allow for fair quotations, and database rights, which allow extractions of insubstantial parts of databases.

The economic case for Article 11 was, moreover, weak. The press publisher right would increase transaction costs considerably, as well as exacerbating existing power asymmetries in media markets. The Statement pointed to the ineffectiveness of the German and Spanish press publisher regimes as additional reasons not to create such an EU-wide right.

The Max Planck Institute’s Center for Innovation and Competition also published a Position Statement opposed to Article 11.3 The European Copyright Society’s response to the European Commission’s public consultation on the role of publishers in the copyright value chain raised significant questions about the proposed press publishers’ right.2

The Bently et al. report noted that online journalists perceive the new right as a threat to the nature of news communication in the modern era: "Paying for links is as absurd as paying for citations in the academy would be." That report cast doubt on the wisdom of adopting a provision such as Article 11.

Will Compromise Provisions Overcome Opposition?

To respond to concerns expressed by various critics, the European Parliament in September 2018 approved several amendments to Article 11. For instance, it proposed creating an exception for individual users to make "legitimate private and noncommercial uses" of press contents.

The compromise text made public in November 2018 contains a similar, although differently worded, provision. It states that the press publisher rights "shall not apply to uses of press publications carried out by individual users when they do not act as information society service providers." This is, however, still quite vague. Would it, for instance, exempt a person or nonprofit organization that regularly blogs with links to EU press publisher sites?

It remains unclear whether hyperlinking to press publisher contents will generally be lawful.

The Parliament-approved version also provided that "mere hyperlinking accompanied by individual words" would not trigger liability. However, the latest compromise text has retained the Commission’s original version of Article 11, which would extend liability to hyperlinking if it constituted a communication to the public.

Because the communication right in respect of hyperlinking is an ever-evolving concept under some very confusing CJEU decisions, it remains unclear whether hyperlinking to press publisher contents will generally be lawful.

Yet, the November 2018 compromise text would qualify the press publisher right by providing that "uses of insubstantial parts of a press publication" should not give rise to liability. Moreover, member states could determine what parts of press publications are "insubstantial" by "taking into account whether these parts are the expression of the intellectual creation of their authors, or whether these parts are individual words, or very short excerpts." This qualification is better than nothing, but notice how vague is the concept of "insubstantial" and what if member states differ on how many words are too many?

Another qualification proposed in a recital to the compromise text indicates the rights should not extend to "mere facts" reported in the press publications. Again, this is better than no such limitation, but it begs the question of what "mere facts" includes and does not include.

The Parliament’s version of Article 11 would have cut the duration of the proposed press publisher right to a five-year term in contrast to the Commission’s original proposal of 20 years from publication. But when it comes to news, even five years seems unduly long. The November 2018 compromise text would follow the German law in granting press publishers these rights for only one year.

Finally, the Parliament-approved version of Article 11 proposed requiring press publishers to provide authors with a "proportionate" share of whatever revenues the publishers collect from licensees of the new right. This might well reduce (perhaps by half) the benefits to publishers from creation of this new IP right. Or it may instead lead to much higher license fees to fund the author-sharing. The November 2018 compromise text retains this proposal.

As well-meaning as the author-sharing proposal may be, it underestimates how substantial will be the costs necessary to obtain sufficient information to determine which authors are entitled to get what part of each press publisher’s revenues.

Conclusion

A key assumption underlying the proposed DSM Directive, including Article 11, is that strengthening European IP rights will lead to much greater licensing revenues flowing to European rights holders from (mostly) American technology companies. (See my November 2018 column discussing the even more controversial Article 13 of this Directive.)

European press publishers have lobbied heavily for this new right and seem on the verge of getting a significant boost in leverage this right will give them to negotiate for new revenue streams from search engines and news aggregators. The German and Spanish experiences thus far cast doubt on the prospects for significant successes. Whether an EU-wide right will achieve better results remains to be seen. Maybe Google and Facebook will pay up, but maybe not.

There is, of course, some irony in the EU’s prospective adoption of a Directive aimed at promoting a "digital single market" given that no one licensing entity exists from which technology firms can get an EU-wide license. Each member state will have its own implementation of the DSM directive. Prospective licensees will have to negotiate with every member states’ preferred collecting society to clear all the rights necessary to make digital uses of European journalistic contents.

Even if Google and Facebook decide to take licenses from European press publishers and can afford to negotiate all of the necessary licenses, isn’t there a significant risk these licenses will further entrench them as dominant players in global information markets? The new press publisher right would seem to impose significant transaction costs as well as establish expensive licensing fees for some individual bloggers, innovative startups, and small enterprises that may want to link to journalistic contents from European sites.

While there is very little chance at this point that Article 11 will be deleted from the DSM Directive, some further compromises may be negotiated by those responsible for finalizing its text so that freedom of information and expression are not unduly repressed by adoption of this unfortunately ambiguous new IP right.

A closed-door "trilogue" is under way among representatives of the European Commission, the Council, and the Parliament, each of which has supported a different version of Article 11. The November 2018 compromise text will likely not be the last word. Other nations should, however, be wary of following the EU’s lead on this particular initiative.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment