Computing has changed significantly since the launch of ChatGPT in 2022. For decades, artificial intelligence (AI) was a subfield of computer science that overpromised and underdelivered. Language mastery has been the holy grail of AI from its early days. Suddenly, computers can communicate fluently in natural language—sometimes nonsense, but always in a very polished language. Suddenly, the dream of artificial general intelligence, which always seemed beyond the horizon, does not seem so far off.

In January 2024, a survey of thousands of AI authors on the future of AI was publisheda on arXiv. While the survey quickly came under some criticism,b its main message cannot be ignored: The AI community clearly has deep concerns about where the field is heading. Human-extinction risk often dominates discussions about AI risks, but the survey revealed deep concerns about other significant risks, such as the spread of false information, large-scale manipulation of public opinion, authoritarian control of populations, worsening economic inequality, and more.

There was little agreement among the surveyed authors on what to do about these concerns. For example, there was disagreement about whether faster or slower AI progress would be better for the future of humanity. There was, however, broad agreement that research aimed at minimizing potential risks from AI ought to be prioritized more. So, I went to the call for papers of NeurIPS 2024, one of the largest AI conferences, and searched for the word “risk.” I did find it; submissions that do not meet some requirements “risk being removed without consideration.” In fairness, NeurIPS papers are required to adhere to the NeurIPS Code of Ethicsc and may be subject to an ethics review, in which the issue of harmful consequences will be considered, but the topic of AI risks has yet to become a major topic at NeurIPS.

The point here is not to single out NeurIPS. The concerns of the AI community about the direction of their field cannot be addressed by one researcher at a time or one conference at a time, just as concerns about climate change cannot be addressed by individual actions. These concerns require a collective action. Is the AI community capable of agreeing on a collective action?

ACM is the largest professional society in computing. It has a special interest group on artificial intelligence (SIGAI), but SIGAI does not sponsor major AI conferences or journals. ACM does co-sponsor the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, yet the general sense is that ACM allowed itself to “lose” AI many years ago. In fact, AI has its own professional association, the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), which does sponsor the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. But this North America-based conference has a “sister” conference, the International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI), which is an independent professional society. Past attempts to bring AAAI and IJCAI together have failed. Furthermore, the huge growth over the past decade has been in the area of machine learning. NeurIPS 2023, for example, was attended by more than 13,000 participants. NeurIPS is sponsored by the NeurIPS Foundation, yet another professional society. The AI community is badly fragmented, which makes it quite challenging to agree on collective actions. Hence the sense of crisis.

A deeper chasm in the AI community is between academia and industry. Academic researchers are comfortable with the ACM Code of Ethics,d which requires computing professionals to consistently support the public good. But industrial researchers typically work at for-profit corporations, who often pay lip servicee to corporate social responsibility, but, in practice, typically focus on profit maximization. As Jeff Horwitz wrote in his 2023 book, Broken Code,f about Facebook: “The chief executive, and his closest lieutenants have chosen to prioritize growth and engagement over any other objective.” With Big Tech consisting of six corporations with more than one trillion dollars in market capitalization, their research budgets dwarf governments’ research budgets in computing. Furthermore, industrial researchers have access to large-scale data and computing that academic researchers can only dream of.

So where does the field go from here? I believe that we must find a way to pick up the baton of social responsibilityg that was left on the ground when Computer Professionals for Social Responsibility was dissolved in 2013. Social responsibility is significantly more central to computing today than it was then. I would like to see one of our professional societies lead the AI community by acting as convenor and moderator for a community-wide conversation about the future of AI. Such a conversation is badly needed.

You wrote, “For decades, artificial intelligence (AI) was a subfield of computer science that overpromised and underdelivered.” It is still doing that. It is far easier to imitate a conversation than to actually have one, The late Prof. Joeseph Weizenbaum showed us us that in the 1960s with his Eliza/Doctor chatbot. People were easily fooled then and they are still easily fooled. That’s why these II (Imitation Intelligence) programs still produce complete nonsense on occasion. Humans do that too. Neither can be trusted.

I have just read “Is Computing a Discipline in Crisis?” and I totally agree that we need to restart “Computer Professionals for Social Responsibility” today!

I was a member of the historical CPSR, now ACM member and ACM SIGCAS member, teaching Computer Ethics at Politecnico of Torino (Italy) and member of the ACM Committee on Professional Ethics …

I am also ready to collaborate if there is a team of people interested …

Greetings from Italy

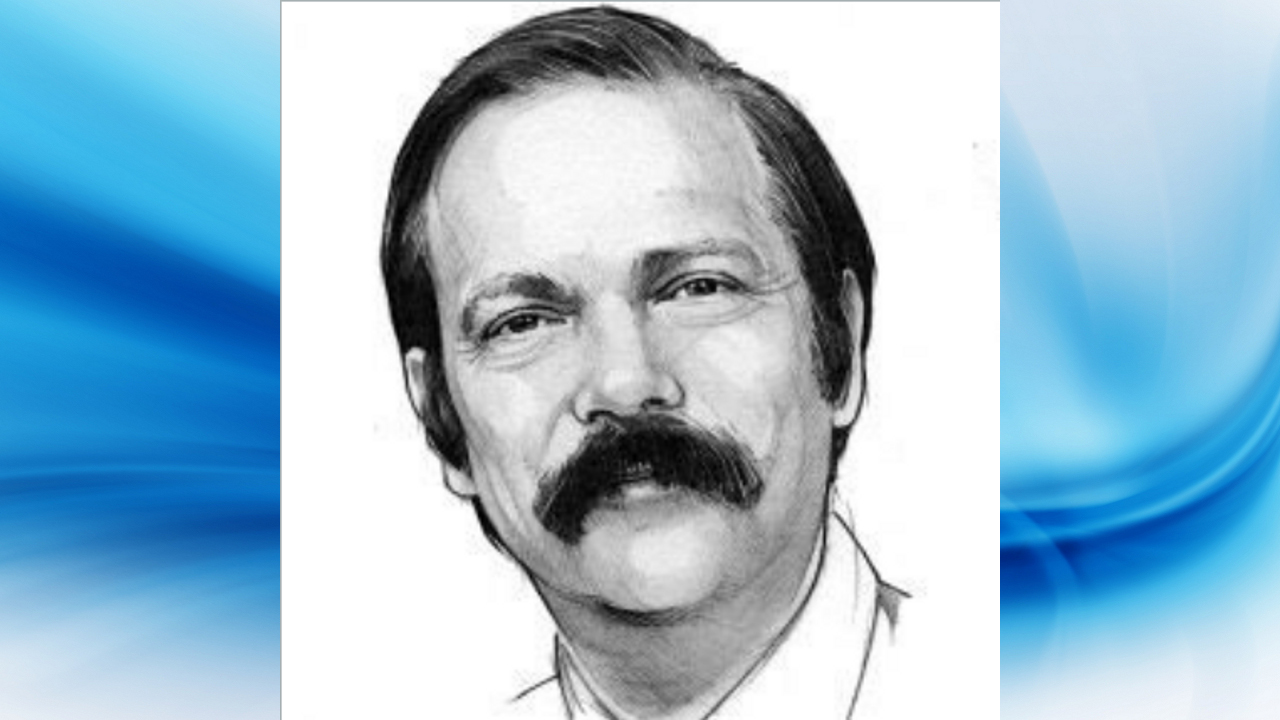

Norberto Patrignani