In August 2000, Intel briefly had a market value of $509 billion (more than $930 billion in 2024 dollars). It was the most valuable public company and the “platform leader” in the personal computer industry along with Microsoft. At the start of December 2024, Intel’s value stood at $104 billion (after falling under $100 billion), far below Microsoft ($3.1 trillion) and Apple ($3.6 trillion). Nvidia ($3.4 trillion) became the new leader in semiconductors, rivaling Apple in market value. Intel also had fallen behind long-time rival AMD ($222 billion) as well as Broadcom ($176 billion), Qualcomm ($174 billion), and ARM ($141 billion). Then we have Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., known as TSMC, valued at $958 billion.

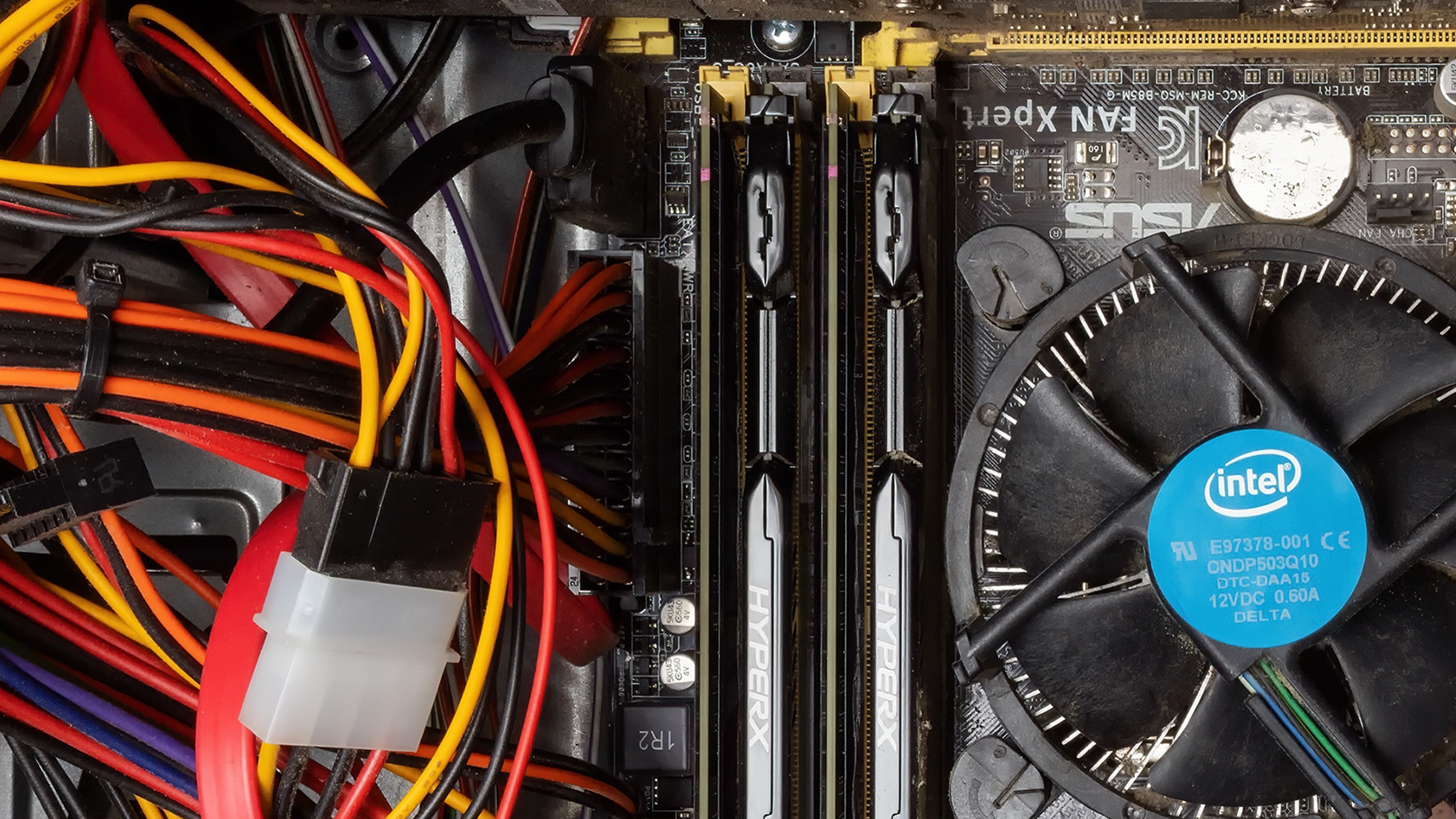

Intel microprocessors, also called central processing units (CPUs), have powered DOS-based and then Windows PCs since IBM introduced its personal computer in 1981. Intel later used this architecture to dominate datacenter servers. However, PC sales have matured, and datacenters are increasingly running generative AI software on Nvidia graphical processing units (GPUs). In October 2024, Intel announced huge restructuring charges and the largest quarterly loss in the company’s history—$16.6 billion—as well as layoffs of 16,500 employees.11 Intel also canceled its dividend and fielded at least one acquisition offer.2 In November 2024, Nvidia replaced Intel in the Dow Jones Stock Index.5

How did Intel’s “fall from grace” happen? What should managers learn from this story? I have followed Intel as well as Microsoft and Apple closely since the early 1990s. The business media and several former Intel directors also have weighed in on Intel’s struggle and options.21 What happened to Intel falls into two “buckets.” One involves the challenge of dominating a highly profitable market without having the foresight, ability, or flexibility to adapt to new technologies and customers (for example, mobile and AI) as they emerged. A second relates to the consequences of maintaining a strategic commitment (such as in-house manufacturing) that has become outdated. Intel’s determination to keep making its own microprocessors had been an advantage, but it became a liability as advanced semiconductor manufacturing evolved into a highly specialized capability, separable from design.

Platform Leadership: The Blessing and the Curse

Andy Grove, while Intel CEO from 1987 to 1998, laid out a platform strategy aimed at growing the entire PC ecosystem, with Intel’s x86 microprocessors and Microsoft’s operating systems at the center.13,14 Driving ecosystem growth was Moore’s Law, which inspired the creation of Intel as well as Microsoft and Apple.

In 1965, while working for Fairchild Semiconductor, Intel co-founder Gordon Moore looked at several years of data. He observed that semiconductor devices were doubling in power (number of transistors on a silicon wafer) every year or so. Looking forward, he reasoned that computers would someday be cheap and ubiquitous. Moore and Bob Noyce—coinventor of the integrated circuit—founded Intel in 1968 with venture capitalist Arthur Rock precisely to keep pushing forward Moore’s Law and master the mass production of increasingly powerful semiconductor devices. In 1975, Bill Gates and Paul Allen came to the same conclusion that computers would someday be everywhere and established Microsoft to “productize” (write once, sell a million times) the software programming languages and then other basic programs that all personal computers would need to be useful. In 1976, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak came to the same conclusion and co-founded Apple, convinced that, since computers were going to be everywhere, the user interface should be as easy to use as any consumer appliance. This conviction led to the Apple II (1977) and later the Macintosh (1984).6,22

Grove’s intention was for Intel to develop and share technology for software applications such as telephony, faxing, videoconferencing, and multimedia processing on the PC that would keep generating demand for ever-more-powerful microprocessors. Intel also designed technologies such as universal serial bus (USB) to make it easier for manufacturers to connect their peripherals.13 These “complementary innovations” and some five million software applications by the mid-1990s entrenched Windows-Intel (“Wintel”) as the dominant platform for desktop computing.7 Microsoft and Intel maintained 85% to 95% of this PC market for decades, and still claim over 70%.a During 2005-2007, Intel also managed to convince Apple to switch from IBM’s PowerPC to Intel chips, which improved the Macintosh’s processing power as well as interoperability with Windows files.

When growth in mobile devices started to take off in the 2000s, Microsoft and Intel were left behind. Windows required too large a screen interface and Intel microprocessors consumed too much power. Enter Steve Jobs! After having lost the PC platform battle, Apple revived its fortunes with the iPod and iTunes for Windows (2003) and then the iPhone (2006). Other firms such as ARM, Qualcomm, and Samsung came to dominate semiconductors for mobile platforms, while Google offered a free operating system, Android.

Before AMD and ARM server designs ate into its market share, Intel provided as much as 90% of data-center CPUs and still accounted for over 75% of new shipments in 2024.b However, Intel gradually fell behind in manufacturing technology, and this impacted performance of its core microprocessors. Most telling here is Apple’s decision in 2019 to abandon Intel as a supplier for MacBook and desktop computers and, instead, shift to its own in-house chips. Apple chose the reduced instruction-set ARM architecture, which uses less battery power.1 Apple also boasted that its own chips, made by TSMC, had higher performance and quality than Intel’s.12

Microsoft has fared much better than Intel. Both struggled with the transition to mobile devices and cloud computing, and Microsoft’s stock price stagnated before Satya Nadella became CEO in 2014. Nonetheless, users still purchased computers bundled with Windows as well as Office, and the Azure cloud service gradually won over lucrative enterprise customers. And, unlike what Intel faced in manufacturing, the marginal cost of reproducing software and automated digital services is close to zero, even though datacenters are expensive. More recently, Microsoft has incorporated artificial intelligence and machine learning into its products and services, and since 2019 has invested an estimated $13 billion in OpenAI to bolster these capabilities.15 Intel purchased Israel’s Habana Labs in 2019 for $2 billion to accelerate its own AI and GPU chip development, though this decision clashed with another acquisition made several years earlier.16

Most difficult for Intel (and other competitors) to overcome has been Nvidia’s advantage in both hardware and software, like Intel and Microsoft combined have had for the PC platform. First, there is the proprietary Nvidia GPU architecture, which processes thousands of simple instructions in parallel, originally designed for graphics but perfect for running neural-network software. Second, there is Nvidia’s huge investment in CUDA (Compute Unified Device Architecture) programming tools and libraries, which are free but work only with Nvidia GPUs. Both innovations date to 2006, giving Nvidia an enormous lead.8 In response, Intel and AMD have made their GPU SDKs open-source, but it will take years for them and the open source community to develop enough software assets to compete effectively with Nvidia.9

Self-Manufacturing: The Blessing and the Curse

Another industry change turned an Intel strength into a glaring disadvantage: the commitment to manufacture its own designs. The cost implications are staggering. In 2023, Intel spent 48% of revenues—nearly $26 billion—on capital investment.10 By contrast, Nvidia spent $1.1 billion—merely 1.8% of revenues (though up from 6.7% the prior year: see the accompanying table). In 2023, AMD spent 2.4% ($546 million). Like Intel, TSMC spends nearly half of revenues on capital expenditures but, unlike Intel, it does not have to invest in product R&D.

| Note: Fiscal years overlap calendar years | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|

| Intel | ||

| Capital Expenditures | $25 billion | $26 billion |

| Revenues | $63 billion | $54 billion |

| Percentage | 40% | 48% |

| AMD | ||

| Capital Expenditures | $450 million | $546 million |

| Revenues | $24 billion | $23 billion |

| Percentage | 1.8% | 2.4% |

| Nvidia | ||

| Capital Expenditures | $1.8 billion | $1.1 billion |

| Revenues | $27 billion | $61 billion |

| Percentage | 6.7% | 1.8% |

| TSMC | ||

| Capital Expenditures | $35 billion | $31 billion |

| Revenues | $76 billion | $69 billion |

| Percentage | 46% | 45% |

Intel’s failure to keep up with TSMC was not simply a matter of money, however. Intel executives and engineers greatly overestimated their ability to transition from 14nm to 10nm and then 7nm gate widths without adopting EUV (extreme ultraviolet) lithography from the only supplier that offered this technology, ASML.12 TSMC partnered with ASML and adopted EUV in 2019.17

For many years, both the capital investment and process knowledge required for advanced semiconductor manufacturing, along with the proprietary x86 architecture, deterred competitors from making Intel-compatible microprocessors. AMD did enter this business but it had become a second source for early x86 microprocessors in the 1970s and then continued this role at the insistence of IBM for its PC in 1982.18 Because Intel and Microsoft have maintained backward compatibility, AMD has been able to continue designing Intel-compatible CPUs as well as make other products. Nonetheless, AMD realized in 2008 that it could not keep up with capital investment requirements and spun off its manufacturing division as Global Foundries and soon after outsourced its most complex microprocessor designs to TSMC.21 Nvidia also has been outsourcing production to TSMC since 1998.20

Founded in 1987 by Morris Chang, TSMC now has unmatched capabilities and scale in advanced semiconductor manufacturing and is the preferred foundry for the world’s top technology companies.4 Given Taiwan’s precarious political relationship with China, the U.S. government wants Intel to survive and has promised $8.5 billion dollars in direct funding and $11 billion in loans through the CHIPS ACT so that Intel can open a new state-of-the-art factory in the U.S.19 Former CEO Pat Gelsinger (he resigned December 1, 2024) was also trying to establish an independent foundry business to bolster Intel’s scale and revenues. Although he lined up two relatively small contracts from Amazon and the U.S. military, Intel’s new factory plans have encountered delays and technical hurdles, and still has insufficient customers.3

Lessons learned? First, moving beyond your historical competitive advantage is extremely difficult while you are still highly profitable and market change seems slow. But that is exactly when companies must prepare for the future. Good times are when you have the money to invest and experiment. Now, there is no longer enough demand for Intel’s products to fund a competitive manufacturing operation. Nor do potential customers want to become reliant on Intel’s fledgling foundry business. Second, to insist that your strategy is right even when nearly all other firms have concluded the opposite smacks of hubris and inflexibility. Platform markets are driven by powerful network effects and can change very quickly or very slowly. Intel has been riding the same x86 Wintel wave for the past four-plus decades. Now it needs help from the U.S. government as well as competitors.

Perhaps most ironic is the opportunity Intel missed in 2005. Then-CEO Paul Otellini floated the idea of bolstering Intel’s graphics business by buying Nvidia for $20 billion, approximately 10 times Nvidia’s annual revenues at the time. His board of directors rejected the idea, due to the price and Intel’s history of not easily absorbing acquisitions.16 Now, Intel is the acquisition target and its survival is in doubt.

I find it astonishing that the article doesn’t even mention Intel’s highly marketing-driven attempt to destroy all competition with its IA64 VLIW (“Itanium”, or, tongue-in-cheek “Itanic”) architecture, a bit before AMD decided to widen the instruction set of the x86 to 64 bit on its own, taking the lead (it also took the lead in building CPUs that were not wasteful of energy, but that’s a parallel story). Did IA64 sink without any trace at all?

Another management decision by Intel that complements your point about companies needing to ‘move beyond your historical competitive advantage […] when times are good and experiment’ is their implementation of the ‘Copy Exactly’ strategy at their manufacturing facilities. While this approach was designed to improve manufacturing reliability and profitability in the short term, I hypothesize that it also contributed to Intel’s downfall, as it deemphasized the long-term advantages of diverse ideas in the workplace. If Intel had invested in an EUV (Extreme Ultraviolet Lithography) manufacturing plant while continuing to develop DUV (Deep Ultraviolet) technology, they might have been able to transition more smoothly when DUV started to falter. Additionally, if each DUV plant had incorporated slight variations, Intel could have experimented to determine which advancements led to better results. However, this would have required a larger investment and deviated from the efficiency-focused ‘Copy Exactly’ approach.