In 1945 my father, Max Newman, who had been working at Bletchley Park during the Second World War, was appointed head of the Mathematics Department at Manchester University. At that time my parents, my brother Edward, and I were living at Cross Farm in the village of Comberton, near Cambridge. My father’s new job required us to move close to Manchester, and my parents therefore bought a house in Bowdon, Cheshire. In 1946 we moved there from Cross Farm, which was rented out to tenants.

During the postwar years a steady stream of academics visited us at the Bowdon house. Some of them were bright young mathematicians who were being considered for teaching posts in the department. Others were more senior academics, invited by my father to give lectures: John Cockcroft, Mary Cartwright, Henry Whitehead, Norbert Wiener, and others. In those postwar years it would have been expensive for these visitors to stay in hotels, so they stayed with us, usually for just one night.

During the late 1940s our most frequent guest was Alan Turing. In 1946 my father, having secured a substantial grant from the Royal Society for computer research, had offered Alan a position as a Reader in the Mathematics Department, and Deputy Director of the Computing Laboratory. Alan accepted, taking up the position in 1948 and later buying a house ("Hollymeade") in Wilmslow, eight miles from Bowdon. Living so close, Alan was now able to visit us quite frequently on weekends. He usually made the journey on his bicycle, which had been fitted with a small gasoline engine. His visits were enjoyed by all of us: by my father, who could sit with Alan and explore avenues for artificial intelligence research; by my mother, who was constantly touched by Alan’s honesty and originality when they talked together; and by me and my brother, both of us happy to have a grown-up friend who liked spending time with us—and spending money on delightful presents for us on our birthdays and at Christmas.

One of Alan’s visits to our Bowdon house, early one autumn morning in 1950, still gives me pleasure to recall. I was asleep in the ground-floor front room, and was awakened by a rustling noise at our front door. I went to open it, and found Alan standing there in his running clothes. He explained that he had set out to run from Wilmslow to Bowdon and back, and on the way had decided to invite us to dinner at his house. Arriving at our front door, he was concerned not to wake us. He had therefore used a twig to scratch his invitation on a leaf that he picked off our rhododendron bush.

I also recall several visits when Alan and I played games. On one occasion he suggested a game of "blindfold" chess, during which he would sit where he could not see the board and would call out his moves, while I would sit with the board in front of me and call out mine. The game got under way, my father watching its progress in silence. After a while Alan excused himself and left the room. He was gone for a several minutes, during which time my father took the opportunity to point out that my king was in a precarious position. Eventually Alan—who must have realized this—returned and announced the winning move. I believe he had not wanted to upset me by winning, and had left the room to steel himself for issuing his coup de grace.

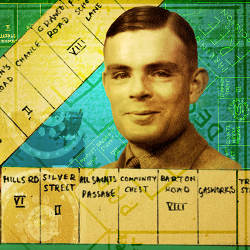

I remember a later phone call from Alan, asking me if Edward and I had a Monopoly set. I replied that we did, and was delighted when he suggested we three might play a game when he next visited. At the time it did not occur to me to mention that our "set" was homemade, with a "board" drawn by me on a sheet of paper. I could also have told him that its layout was somewhat unorthodox—I had added an extra row of properties, diagonally connecting the "GO" square to the square on the opposite corner. I cannot recall why I had done this, but I may have wanted to provide a choice of routes. In the end Alan lost—neither Edward nor I showed him any mercy. [The original homemade Monopoly board was discovered last year in the Newmans’ old family home and was recently released as a special edition: see http://www.heritageandhistory.com/contents1a/2011/06/monopoly-board-secured-by-spy-hq/. William Newman’s original game-board drawing is on display at the Bletchley Park Museum.—Ed.]

Living so close, Alan was able to visit us quite frequently on weekends.

It was at around this time that Alan inadvertently attracted the attention of the Times, by giving a talk about the computer research in Manchester. My mother described the event in a letter to a friend: "Did you see the extraordinary report in the Times two weeks ago on the Manchester Calculating Machine with the fantastic remarks attributed to Alan Turing? And Max’s letter the following week trying to clear things up? The Times wired Alan, who isn’t on the telephone, to ring their office, and they interviewed him on the phone. He’s wildly innocent about the ways of reporters and has a bad stammer when he’s nervous or puzzled. It was a great shock to him when he saw the Times—and to Max who had been flying back from Belfast that day. We had a wretched weekend starting at midnight on the Friday night when some sub-editor of a local paper rang up to get a story. By Sunday Max was getting a bit gruff, and when he said, ‘What do you want?’ to one newspaper, the reporter replied, ‘Only to photograph your brain.’"a

For my parents, moving to Manchester meant finding me a local school, but none of the local grammar schools taught mathematics to a standard that satisfied my father. Meanwhile, my mother was having trouble finding suitable tenants for Cross Farm, and after four years in Bowdon she was missing her Cambridge friends and her sister Yda in London. In April 1950 she therefore moved back to Cross Farm with me and Edward, and my father found an apartment in Bowdon where he could stay during term time. I was enrolled at the County grammar school in Cambridge, where I received extra tuition in mathematics from a genial Yorkshireman, Tom Marsden. My father approved of this choice of school, possibly because the headmaster, Brinley Newton-John, had worked at Bletchley Park.

Our move to Cross Farm separated us from Alan, and both my mother and I missed him greatly. She had become very fond of Alan over the years, and he had opened up to her. I have no memories of having any contact with Alan during the last four years of his life. Somehow my parents ensured I was unaware of his 1952 conviction for gross indecency. News of his death reached us at Cross Farm on June 8, 1954, the day after his body was discovered: the phone rang while my mother and I were in the living room, and she answered it. I could tell at once that the call was from my father and that the news was bad. My mother sat huddled over the phone, saying very little except to ask questions: Had Dr. Greenbaum, Alan’s psychiatrist, been informed? She was in floods of tears when the call ended, and all she could then say to me was that Alan had taken his own life. Later that day she felt able to say a few more words. She told me that Alan was a homosexual, and explained what that term meant. A few days later she attended Alan’s funeral, and handed the letters she had received from him to his brother John. A chapter in our lives had come to an end.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment