“Social entrepreneurs are not content just to give a fish or teach how to fish. They will not rest until they have revolutionized the fishing industry.”

—Bill Drayton, Leading Social Entrepreneurs Changing the World

Entrepreneur Elliot Kotek and his business partner Mick Ebeling have taken Bill Drayton’s observation to heart, working to ensure technology can not only help those in need, but that those in need may, in turn, help create new technologies that can help the world.

Kotek and Ebeling co-founded Not Impossible Labs, a company that finds solutions to problems through brainstorming with intelligent minds and sourcing funding from large companies in exchange for exposure. Unlike most charitable foundations or commercial developers, Not Impossible Labs seeks out individuals with particular issues or problems, and works to find a solution to help them directly.

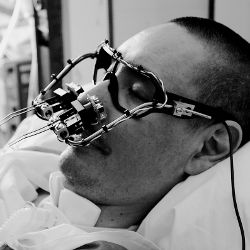

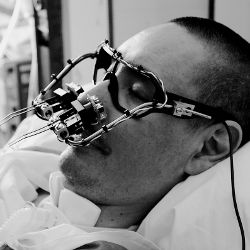

Not Impossible Labs initially began in 2009, when co-founder Mick Ebeling organized a group of computer hackers to find a solution for a young graffiti artist named Tempt One, who was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and quickly became fully paralyzed, unable to move any part of his body except his eyes.

The initial plan was simply to do a fundraiser, but the graffiti artist’s brother told Ebeling that more than money, the artist just wanted to be able to communicate. Existing technology to allow patients with severely restricted physical movement to communicate via their eyes (such as the system used by Stephen Hawking, the noted physicist afflicted with ALS, or Lou Gehrig’s disease) cost upward of $100,000 then, which was financially out of reach for the young artist and his family.

As a result of the collaboration between the hackers, a system was designed that could be put together for just $250, which allowed him to draw again. “Mick Ebeling brought some hackers to his house, and they came up with the Eyewriter software, which enabled him to draw using ocular recognition software,” Kotek explains.

Ebeling continued to put together projects designed to bring technology to those who were not in a position to simply buy a solution.

Based on the success of the Tempt One project, Ebeling continued to put together projects designed to bring technology to those who were not in a position to simply buy a solution. He soon attracted the attention of Kotek who, with Ebeling, soon drew up another 20 similar projects that they wanted to find solutions for in a similar way.

One of the projects that received significant attention is Project Daniel, which was born out of the duo’s reading about a child living in the Sudan, who lost both of his arms in a bomb attack. “We read about this doctor, Tom Catena, who was operating in a solar-powered hospital in what is effectively a war zone, and how this kid was struck by this bomb,” Kotek says, noting that he and Ebeling both felt there was a need to help Daniel, or someone like him, who probably did not have access to things such as modern prostheses. “It was that story that compelled us to seek a solution to help Daniel or people like him.”

The project kicked off, even though Not Impossible Labs had no idea whether Daniel was still alive. However, when a group of specialists was pulled together to work on the problem, they got on a call with Catena, who noted that Daniel, several years older by now, was despondent about his condition and being a burden to his family. After finding out that Daniel, the person who inspired the project, was still alive and would benefit directly from the results of the project, the team redoubled its efforts, and came up with a solution that uses 3D printers to create simple yet customized prosthetic limbs, which are now used by Daniel.

The group left Catena on site with a 3D printer and sufficient supplies to help others in the Sudan who also had lost limbs. They trained people who remain there to use the equipment to help others, generalizing the specific solution they had developed for Daniel. That is emblematic of how Not Impossible works: creating a technology solution to meet the need of an individual, and then generalizing it out so others may benefit as well.

Not Impossible is now establishing 15 other labs around the world, which are designed to replicate and expand upon the solutions developed during Project Daniel. The labs are part of the company’s vision to create a “sustainable global community,” in which solutions that are developed in one locale can be modified, adapted, or improved upon by the users of that solution, and then sent back out to benefit others.

That is emblematic of how Not Impossible works: creating a technological solution to meet the need of an individual, and then generalizing it out so others may benefit as well.

The aim is to “teach the locals how to use the equipment like we did in the Sudan, and teach them in a way so that they’re able to design alterations, modifications, or a completely new tool that helps them as an indigenous population,” Kotek says. “Only then can we look at what they’re doing there, and take it back out to the world through these different labs.”

Project Daniel was completed with the support of Intel Corp., and Not Impossible Labs has found other partners to support its other initiatives, including Precipart, a manufacturer of precision mechanical components, gears, and motion control systems; WPP, a large advertising and PR company; Groundwork Labs, a technology accelerator; and MakerBot, a manufacturer of 3D printers. Not Impossible Labs will create content (usually a video) describing the problem, and detail how a solution was devised. Supporting sponsors can then use this content as a way to highlight their support projects being completed for the public good, rather than for profit.

“We delivered to Intel some content around Project Daniel,” Kotek explains, noting that the only corporate branding included with the video about the project is a simple “Thanks to Intel and Precipart for believing in the Not Impossible.” As a result of the success of the project, “Now other brands are interested in seeing how they can get involved, too, which will allow us to start new projects.”

One of the key reasons Not Impossible Labs has been able to succeed is due to the near-ubiquity of the Internet, which allows people from around the world to come together virtually to tackle a problem, either on a global or local scale.

“What we want to do is show people that regular guys like us can commit to helping someone,” Kotek says. “The resources that everyone has now, by virtue of just being connected by the Internet, via communities, by hacker communities, or academic communities … We can be doing something to help someone close to us, without having to be an institution, or a government organization, or a wealthy philanthropist.”

Although Not Impossible Labs began as a 501(c)(3) charitable organization, it recently shifted its structure to that of a traditional for-profit corporation. Kotek says this was done to ensure the organization can continue to address a wide variety of challenges, rather than merely the cause du jour.

“As a foundation, you’re subject to various trends,” Kotek says, highlighting the success the ALS Foundation had with the ice bucket challenge, which raised more money in 2014 than the organization had in the 50 preceding years. Kotek notes that while it is a good thing that people are donating money to ALS research as a result of the ice bucket challenge, such a campaign generally impacts thousands of other worthy causes all fighting for the same dollars.

Not Impossible Labs is hardly the only organization trying to leverage technology to help people. Japanese robotics company Cyberdyne is working on the development of the HAL (hybrid assistive limb) exoskeleton, which can be attached to a person with restricted mobility to help them walk. Scientists at Cornell University are working on technology to create customized ear cartilage out of living cells, using 3D printers to create plastic molds to hold the cartilage, which can then be inserted in the ear to allow people to hear again.

Yet not all technology being developed to help people revolves around the development of complex solutions to problems. Gavin Neate, an entrepreneur and former guide dog mobility instructor, is developing applications that take advantage of technology already embedded in smartphones.

His Neate Ltd. provides two applications based around providing greater access to people with disabilities.

The Pedestrian Neatbox is an application that directly connects a smartphone to a pedestrian crossing signal, allowing a person in a wheelchair or those without sight to control the crossing activation button via their handset. Neate Ltd. has secured a contract with Edinburgh District Council in the U.K. to install the system in crossings within that city, which has allowed further development of the application and system.

Meanwhile, the Attraction Neatebox is an application that can interface with a tourist attraction, sending pre-recorded or selected content directly to a smartphone, to allow those who cannot physically visit an attraction a way to experience it. The company has conducted a trial with the National Air Museum in Edinburgh, and the company projects its first application will go live in Edinburgh City Centre by the end of 2014.

Neate says that while his applications are useful, truly helping people via technology will only come about when developers design products from the ground up to ensure accessibility by all people.

“Smart devices have the potential to level the playing field for the very first time in human history, but only if we realize that it is not in retrofitting solutions that the answers lie, but in designing from the outset with an understanding of the needs of all users,” Neate says. “Apple, Samsung, Microsoft, and others have recognized the market is there and invested millions. They have big teams dedicated to accessibility and are providing the tools as standard within their devices.”

Like Kotek, Neate believes genuinely innovative solutions will come from users themselves. “I believe the charge, however, is being led by the users themselves in their demand for more usable and engaging tools as their skills improve,” he says, noting “most solutions start with the people who understand the problem, and it is the entrepreneurs’ challenge (if they are not the problem holders themselves) to ensure that these experts are involved in the process of finding the solutions.”

Indeed, the best solutions need not even be rooted in the latest technologies. The clearest example can be found in Jason Becker, a now-45-year-old composer and former guitar phenomenon who, just a few short years after working with rocker David Lee Roth, was struck by ALS in 1989 at the age of 20.

Though initially given just a few years left to live after his diagnosis, he has continued to compose music using only his eyes, thanks to a system called Vocal Eyes developed by his father, Gary Becker. The hand-painted system allows Becker to spell words by moving his eyes to letters in separate sections of the hand-painted board, though his family has learned how to “read” his eye movements at home without the letter board. Though there are other more technical systems out there, Becker told the SFGate.com Web site that “I still haven’t found anything as quick and efficient as my dad’s system.”

Further Reading

Not Impossible Now: www.notimpossiblenow.com

The Pedestrian Neatebox: http://www.theinfohub.org/news/going-places

Jason Becker’s Vocal Eyes demonstration: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DL_ZMWru1lU

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment