While the relentless rollout of gee-whiz products from Silicon Valley gives many the opportunity to live in a digital wonderland, those who are less fortunate—the blind and the visually impaired—are increasingly finding they can go along for the ride, too.

Once virtually closed out of computing due to its heavy reliance on a visual interface, the visually impaired are getting much more access to the newest technologies thanks to close cooperation between the visually impaired community and technologists.

Leading the industry is Apple's iPhone. After some lobbying from the blind community, the original iPhone was upgraded to enable the visually impaired to navigate the phone with a feature Apple calls 'VoiceOver,' according to Clara Van Gerven, manager of Accessibility Programs for the National Federation of the Blind.

Essentially a text-to-voice screen reader, VoiceOver also enables a visually impaired user to input commands into an iPhone, whether they prefer using hand gestures, a keyboard, or Braille. VoiceOver is especially handy because it has been fully integrated into Apple's iOs, Van Gerven says; "Because Apple's VoiceOver is proprietary, it works the same way on all Apple devices. It's very predictable and user friendly."

Adds Jonathan Lazar, a professor of computer and information sciences at Towson University, "When an accessibility feature is fully integrated into the OS, it tends to be more stable and have fewer technical glitches or crashes, as compared to an after-the-fact add-on."

Equally popular among the blind is Amazon's Echo, the AI smart assistant that sits on your desk, allowing you to interact with a computer via basic voice commands, Van Gerven says. While most of the sighted public was initially drawn to Echo as way to order Amazon.com products via voice, Echo is also designed to enable users to use voice to play music, listen to audio books, and operate appliances.

"Echo has seen broad adoption" among blind and visually impaired users, Van Gerven says.

On Windows, one of the most popular products to help the visually impaired use computers is the Jaws Screen Reader, a device that provides speech and Braille output for many computer applications, according to Geoff Freed, director of technology projects and Web media standards for the National Center for Accessible Media (NCAM), a non-profit organization focused on providing media access equality for people with disabilities.

An open source alternative to Jaws is Nonvisual Desktop Access (NVDA), a free screen reader that allows a blind user to hear text-to-voice input and output on a computer "without spending hundreds to thousands of dollars on a commercial screen-reading product," says Karen Luxton Gourgey, director of the Computer Center for Visually Impaired People at Baruch College. According to its website, the center "has been in the business of Assistive Technology training, research, and service since 1978."

Meanwhile, there's no shortage of products coming down the pike promising to make life easier for the visually impaired.

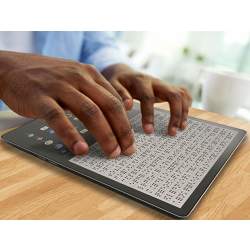

One of the more exciting is Blitab, an Android tablet with a Braille surface designed to render 65 words at a time. The prototype of Blitlab turned heads at the January Consumer Electronic Show in Las Vegas in January, where it was one of 12 finalists in the TechCrunch Hardware Battlefield. Blitab, which will also include text-to-voice capability, is slated to ship before year's end.

Another promising product is Aira, a remote monitoring service that pairs a blind person wearing a pair of smart glasses, like Google Glass, with a remote human monitor. (The name, according to the company's website, is a combination of "the emerging field of Artificial Intelligence (AI), and the ancient Egyptian mythological being and symbol known as the Eye of Ra (RA)." Essentially, Aira, which bills itself as a "visual interpreter for the blind," engages a human monitor to help a visually impaired person navigate outdoors with the help of live video from the blind person's smart glasses, along with GPS tracking.

"Use of glasses for wayfinding has been an area of interest for a long time," says NCAM's Freed.

Users launch Aira by simply double-tapping on the side of their smart glasses; instantly, real-time video of the person's location pops up on the screen of a human monitor in Aira's San Diego headquarters. Beneath the video, a Google map also pops up, pinpointing the person's precise GPS location.

Literally another pair of eyes watching the visually impaired person navigating the outdoors, the Aira human monitor can help guide the user to a restaurant, for example, offering verbal clues on how to navigate streets, hop a train, and even recognize friends based on their Facebook profile pictures.

Meanwhile, apps for smartphones are also helping the visually impaired navigate the outdoors. Be My Eyes, for example, is very similar to Aira in that it connects the camera of a blind person's smartphone to a sighted volunteer who can explain what the phone 'sees.'

Another app, BlindSquare uses GPS to guide the visually impaired. As explained on its website, the app "describes the environment, announces points of interest and street intersections as you travel. In conjunction with free, third-party navigation apps it is a powerful solution providing most of the information blind and visually impaired people need to travel independently. "

While many of these solutions would benefit from the inclusion of facial recognition software, much of the developer community that creates apps for the visually impaired is currently in a quandary over the use of such software, Van Gerven says. She explains that, while these specialist developers see facial recognition's obvious benefits, many are hesitant to create apps that incorporate facial recognition, given the risk of privacy violation inherent in the technology.

"The developers I talk with are very concerned over the ethics of using facial recognition software," Van Gerven says.

Joe Dysart is an Internet speaker and business consultant based in Manhattan.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment