Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania have discovered a way of discerning between liars and truth-tellers: brain scans.

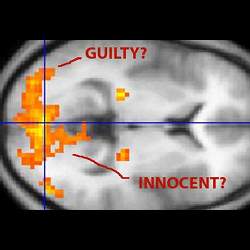

The researchers say they can spot a lie being formed in the brain with up to 90% accuracy by using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). When someone tells a lie during an fMRI scan, decision-making areas of the brain light up, they say, betraying the liar.

The technique is much more accurate than a standard polygraph test, which can be extremely unreliable—sometimes no better than a wild guess, according to the researchers.

“Polygraph measures reflect complex activity of the peripheral nervous system that is reduced to only a few parameters,” says Dr. Daniel D. Langleben, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania. “fMRI is looking at thousands of brain clusters, with higher resolution in both space and time.”

How it works

The researchers used a 3T MRI Scanner from Siemens, augmented with Presentation software from Neurobehavioral Systems and FSL brain imaging software. Together, the hardware/software combination allowed researchers to take numerous snapshots of the inside of the brain as it worked to deceive them. When those snapshots were aligned in sequence by the system, researchers essentially had a video they could play back to watch a lie as it unfolds within the brain, in real time.

Underpinning Langleben’s research is the theory that when telling a lie, the brain must first stop itself from telling the truth; then, it must work to put together a fabrication. That process results in greater activity in certain regions of the brain—activity researchers can capture using an fMRI system.

The assumption is that by culling and studying brain scan videos that correctly identify brain activity related to lying, researchers over time can get a much more precise idea of the kinds of images that indicate a brain is in the act of a lie.

At least two companies in the U.S. already offer fMRI lie-detection scanning services: Truthful Brain and Cephos.

Truthful Brain charges $5,000 for an fMRI scan, although CEO Joel Huizenga says he is willing to reduce that price to $1,000 for volume orders. Cephos did not respond to a request for similar information.

Observes Langleben, fMRI “is no different from any other MRI test. MRI scanner time costs about $500 an hour, and you do not even need a full hour for a test. Everything else is labor, with widely varying costs. A radiologist can charge $2,000 for an interpretation, or she/he can charge $20.”

While Langleben’s study results are encouraging, his fMRI system could have achieved even higher accuracy if it had been coupled with state-of-the art artificial intelligence (AI) software, according to Truthful Brain’s Huizenga. “Modern analytics such as pattern recognition/machine learning were not used to analyze the data in this paper.”

Essentially, an fMRI system souped-up with AI—and trained against a data set of many thousands of images of lying brains—will be much more accurate in identifying signs within the brain that lying is taking place than the method Langleben used: attempting to discern patterns of lying in fMRI results by using human eyeballs alone, Huizenga says.

Adds Henry T. Greely, director of the Stanford Program in Neuroscience and Society (SPINS), Stanford University, “Overall, I would say it is an interesting result, but a great deal of work needs to be done before anyone should conclude that fMRI lie detection is good enough to be used.”

Truth and the Law

Besides the need for greater recognition of the potential to enhance fMRI’s accuracy with AI, Huizenga says fMRI lie detection also faces another major hurdle: the legal community. Apparently, lawyers and the courts are uneasy about bringing into the courtroom a technology that, once perfected, could theoretically render redundant much of the work attorneys, judges and juries do everyday: wresting the truth from opposing parties.

“There is presently a battle for supremacy between lawyers and science,” Huizenga says. “The question is, should lawyers—not trained in science—be able to decide what is science and what is good data?”

Jane Campbell Moriarty, Carol Los Mansmann chair in faculty scholarship and professor of law at Duquesne University School of Law in Pittsburgh, PA, who follows fMRI very closely and has co-authored papers on fMRI and lying with Langlehorn, counts herself among the uneasy.

“Whether an effective lie-detection mechanism is a positive development is an issue about which I have serious concerns,” Moriarity says. “As with many forms of technology, we think about its usefulness without equally evaluating the potential misuse of such technology.

“We should not easily relinquish our privacy of thought to those able to get an MRI machine and the legal permission to use it on us.”

Joe Dysart is an Internet speaker and business consultant based in Manhattan.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment