Human interaction with animals is a common activity the world over, but swivel the spotlight onto animal interaction with humans that is supported by digital technologies and a new world opens up, offering a fresh field of research, valuable commercial markets, and beneficial possibilities for both animals and humans.

Early research studies in animal-human computer interaction and human-animal computer interaction that focuses on animals as much as on humans, as well as prototype products to support these interactions, are the subject of the First International Congress on Animal Human Computer Interaction (AHCI) that will be held during the Advances in Computer Entertainment conference next week in Funchal, Madeira. The aim of the Congress is to consider how animals can benefit from, and be part of, the new age of Internet, games, and other enabling technologies. The motivation is to improve animal welfare, although some participants in the event will share research on projects that are mutually beneficial to both animals and humans.

Adrian Cheok, professor of Pervasive Computing at City University, London and co-chair of the Congress, explains that it will be small, “but will discuss a growing body of research and publications looking at how digital technologies can be used for animal to human and animal to animal communication. There will be papers on the practical use of technology for interaction, discussion on new kinds of communications between species and philosophical papers about the increase of computing in animal welfare.”

The concept of animal-human interaction is not new, but those participating in the Congress hope they will be able to provide a foundation for more extensive and recognized research in the field.

Early projects include a 2012 test of a digital prototype of a game called Pig Chase, which was designed by a group of researchers in the Netherlands. The game provides pigs with a large touch-sensitive display on which a ball of light is moved by a human using a tablet computer. The pig chases the light with its snout and, depending on how the pig interacts with the light, various other light effects appear on the display. The project was designed to research the relationship between pigs and humans through game design. For pigs, its outcome was a game that transforms humans into a source of entertainment; for humans, it enabled play with animals that are normally consumed as meat.

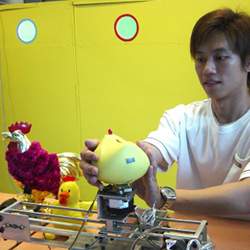

A more recent project led by Cheok is called Poultry Internet, and involved sending hugs to pets via the Internet. The project was carried out in Asia, where chickens may be pets, and was based on the idea that chickens’ affinity to touch could mean that the more they are hugged, the more eggs they lay. The project involved a small chicken avatar with sensors and a ‘pet dress’ for a chicken that includes electronics that simulate touch, or haptic, sensation. When the pet owner ‘hugs’ the avatar, the chicken feels the ‘hug.’

Cheok says, “We did this to see if there was any benefit for chickens. We ran a door test with the chickens choosing whether to go through a door where they would get hugs or through a door where they would not. Most went through the door where they would get hugs. The test showed the self-motivation of the chickens. It is important to demonstrate an increase in the welfare of animals and never build systems that decrease welfare.”

Javier Jaén Martínez, associate professor of computer science and head of ISSI-Futurelab at the Polytechnic University of Valencia, Spain, is also working on projects with animals. There is an animal-centric approach to his work, which considers animals’ fundamental activities, including play. Jaén will present a paper at the Congress discussing how to design interactive and intelligent spaces in which animals can play. He suggests pets at home and animals in zoos are often bored, and could be stimulated by technologies such as robotics, and small devices producing smells that trigger activity.

Jaén also is researching how children in hospitals can interact with their pets at home, and is starting a project that will allow children in hospital to use a computer to observe animals in the Valencia Bioparc zoo. “Children can control the cameras remotely from their beds and follow specific animals. They can talk about their interaction with the animals and think less about their illness. For children in hospital and those who have to go to hospital many times, this is a positive activity and can reduce stress levels.”

Cheok’s co-chair at the congress, Oskar Juhlin of the Mobile Life VinnExcellence Centre at Stockholm University, Sweden, says mobile technologies will change relationships between animals and humans.

One of Juhlin’s projects uses video cameras with proximity sensors that are set up in forests where hunters put food to attract wild boar. Hunters can see videos of wild boar remotely and be alerted to activity by multimedia messages. Juhlin explains, “This project describes the interaction between wild boar and hunters. Its purpose is to understand how to design mobile technology to enrich the lives of people and animals.”

The issue of ethics is picked up by Clara Mancini, head of the Animal-Computer Interaction Lab at the Open University, in Milton Keynes, U.K., and chair of a workshop at the Congress. Says Mancini, “We have developed an ethics protocol for animal-computer interaction research. We had to do this to distinguish our work from other animal experimentation. So far, animal welfare groups understand that our projects are different.”

The protocol does not solve all issues, and Mancini is careful to consider whether animals’ lives will be improved before embarking on projects. “First, we figure out the requirements of animals; this takes time, as you can’t ask an elephant or a dog. Finding this out is part of the methodological challenge.”

Mancini and her researchers are considering how to design interactive toys for elephants in captivity, and are rethinking interfaces so that dogs living with disabled people can perform tasks such as opening doors, turning on the washing machine, and summoning an elevator.

Perhaps her most far-reaching work, albeit still in the laboratory, is around cancer-detecting dogs. With noses thousands of times better than those of humans, dogs can be trained to detect cancer cells in breath or urine. They can signal if they find volatile cells, but only in a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ way, a problem Mancini is breaking down by trying to understand different levels of confidence in how dogs smell samples.

Mancini’s work could have a significant impact on the development of electronic noses for the diagnosis of a variety of diseases. Similarly, Cheok’s work and that of Juhlin and Jaén could open the way not only to improved animal and human welfare, but also to the commercialization of products that benefit animals and humans. While any of these outcomes is possible, perhaps the last words should go to the organizers of the Congress, who state: “The Animal Human Computer Interaction Congress intends to join emerging researchers in an area that promises to be fun, useful, vibrant and very surprising.”

Sarah Underwood is a technology writer based in Teddington, U.K.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment