According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 1 in 68 children in the U.S. have been identified with some level of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Studies in other countries have 1% to 3.5% of their children with ASD. A key diagnostic criterion for the disorder is the delayed development of verbal communication.

To address the challenge of communicating with children with ASD (as well as those suffering from other communicational disabilities, such as stroke victims or those with degenerative diseases), researchers, therapists, and even parents have come up with a wide range of Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) tools over the years. As it turns out, smartphones and tablets have proven to be ideal platforms for such tools, and there are dozens of relevant apps available for both iOS and Android devices.

Pictures to Words

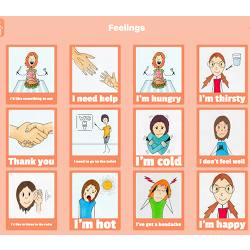

Most of the mobile tools are at least superficially similar to the analog Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS). Developed in 1985, PECS relies on an assortment of cards with pictures on them, which are designed to enable someone with ASD to make requests by choosing the relevant card.

One app using the image-based approach is CommunicoTool. Developed by Frédéric Guibet to help him communicate with his autistic daughter, CommunicoTool’s first version came out in 2012. The app works in English, as well as French.

The mobile platform lets CommunicoTool and similar apps go beyond simply arranging images. For one thing, AAC apps “speak” the words and sentences the user creates, giving a voice to the visual communication. In CommunicoTool’s case, the app can use built-in voices that come with the app, or recorded voices such as that of a child’s parent.

“You have a space of icons and sounds when you install the app,” says Julie Laurent, CommunicoTool’s country manager for the U.S. “If I want, I can hide all the pictograms and only upload new photographs and record my own voice. I can also record my own voice onto a pictogram or icon that’s part of the original database.”

A user’s database of sounds and images is stored in CommunicoTool’s cloud, so a therapist using the app—or the upcoming CommunicoTool Pro, which can support up to 100 different user profiles—can access each user’s custom images and sounds. CommunicoTool is available for iOS and Android devices for $59.99, or $3 a month after a free one-month evaluation.

Language development

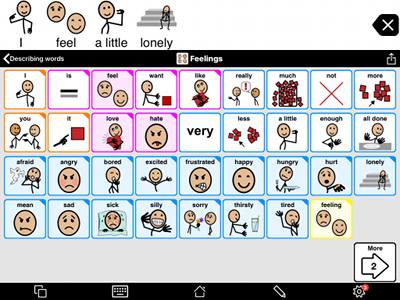

Another picture-based app is AssistiveWare‘s Proloquo2Go, which works in English and Spanish. AssistiveWare CEO and founder David Niemeijer is quick to say his app is more than an expression of PECS, which he says is “very heavily focused on nouns. Proloquo2Go gives access to the full range of communication functions: you can request with it, but you can also comment, change the subject, and ask questions.”

AssistiveWare has been in the assisted communication space since 2005. “We made software that gave full access to the Mac to people with physical disabilities who couldn’t use a physical keyboard or the mouse,” says Niemeijer. At the time, there were AAC systems with dedicated hardware, he says, but they had “a price range of $2,000 or $3,000, up to an iPad-size device for $14,000. When it came out in 2009, Proloquo2Go was the first app to provide a full communication system on a consumer device.” It sells for $249.99 in the App Store.

Proloquo2Go’s range of pictograms enables users

to construct fairly complex sentences.

Proloquo2Go supports buttons with up to 20,000 symbols, and as with CommunicoTool, users can add their own photos. While the app also speaks constructed statements, it does not allow you to record your own voice. “One of the limitations of systems that rely on recording your own voices is that you wind up in a situation where people can only say the things that were recorded for them,” Niemeijer explains. Instead, Proloquo2Go uses text-to-speech synthesis, which can handle not just any word, but any word form.

Swipes, not Pictures

Smartstones’ :prose ($59.99 for iOS) represents a departure from the pictogram-based approach. Like the other apps, :prose speaks the expressions the user creates, but the expressions are generated by swipes on a smartphone screen. Andreas Forsland, Smartstones’ founder and CEO, got the idea for a gesture-based app while his mother was hospitalized with pneumonia; with a ventilator tube down her throat and her mobility restricted, she was unable to speak or text. “Frankly, at that time I didn’t know about these other types of systems,” recalls Forsland. “All I knew was that she needed something really simple just to let me know that she’s doing all right or that she needs help.”

Forsland’s first thought was a device his mother could shake or rub to send predetermined text messages. He pulled together a development team in 2013 to create a test app to see if people could “get” the gesture-to-phrase connection. After they published the app, they started to see interest from the ASD community, as well as from the rehabilitation and special education communities. “This market came to us,” Forsland says.

The product is a complement to other solutions for some users, and an alternative for others, he says. “When you look at autism, it’s a spectrum disorder. What we’ve found is that in the classroom setting, some children prefer our technology over the traditional graphic-based solution because it’s more natural. It’s like a shortcut for phrases, as opposed to having to go and tap through a bunch of menus.”

With :prose able to recognize only about 30 gestures, Forsland acknowledges it does not allow for the same level of free-form sentence construction and flexible concept exploration as some other solutions. However, he says, limiting the number of things a user can say provides its own benefits. “What we’re seeing in the classroom setting is that children are experiencing less mental fatigue using our application,” Forsland says. “As a result, there’s a reduction in outbursts and behavioral intervention needs.”

Users have a private account in the cloud to store their libraries of phrases. By signing into the app with their Apple ID, they can have access to their expressions wherever they have a device. The app also has a chat component, so a child at school, for example, could use a swipe to message parents at home.

Smartstones also makes a palm-sized screenless remote device, the Smartstones Touch, which supports 11 gestures for sending messages and receives input via vibration, light, and sound. Forsland says children using the Touch can maintain eye contact with the person they communicate with, which is not possible when arranging pictograms.

Apps like CommunicoTool, Proloquo2Go, and :prose can open a new world of possibilities to the communication-impaired.

Jake Widman is a San Francisco, CA-based freelance writer focusing on connected devices and other smart home and smart city technologies.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment