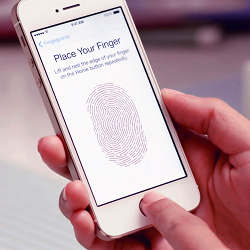

Last September, Apple introduced the iPhone 5s featuring such by-now-expected improvements as a faster chip and higher-resolution camera, as well as a biometric security system—in this case, a fingerprint sensor—that Apple calls Touch ID. This technology allows iPhone owners to capture their fingerprints and then unlock their phones by simply pressing a finger to the Home button.

According to Apple, the odds against two different fingerprints being similar enough to fool Touch ID are 50,000 to 1—much better than the 10,000-to-one odds against guessing a four-digit passcode. On the surface, it sounds like the ideal security system: the keys (your fingers) are always with you, you don’t have to remember anything, and it beats a passcode. What could go wrong?

Two days after the new iPhone went on sale, members of Germany’s Chaos Computer Club, which describes itself as "Europe’s largest association of hackers," announced they had defeated the Touch ID security. Their approach was straightforward: they photographed a fingerprint from the phone, cleaned up the image, printed it on a laser printer, and smeared latex onto the raised toner. After the latex dried, they peeled it off and pressed it to the phone’s sensor, unlocking the phone.

Since those events, Samsung has announced its new Galaxy S5, which also features a biometric lock based on a fingerprint sensor. Samsung describes it as "a secure, biometric screen locking feature and a seamless and safe mobile payment experience to consumers" (the system also lets a user authorize a PayPal payment). The Galaxy S5 will be released April 11, and perhaps because it has not been available, it has not been hacked. Is there any reason to think Samsung’s sensor is more secure than Apple’s?

Michael Horn of the Chaos Computer Club says unequivocally that is not the case. "Biometric ‘security,’ especially (but not limited to) fingerprint recognition, is fundamentally flawed," he says. "All one needs is to reproduce the fingerprint. The grade of sophistication of the sensor just sets the lower bounds for the effort one has to take to come up with a realistic reproduction of a finger."

Samsung’s sensor may pose greater difficulty to hackers, because recording a fingerprint on that handset involves swiping a finger across the sensor, rather than merely pressing on it. "There’s an argument to be made that sliding may leave less residue," says Darren Meyer, a senior security researcher at application security company Veracode, contending it may be harder to lift a fingerprint from a smear than a press. "But the reader is not the weak point. It would be a stretch to think of sliding as a significant advantage."

The major vulnerability in these systems, Meyer says, is that the key is easily accessible. "Fingerprint technology has a deservedly bad reputation because your fingerprints are everywhere," including, of course, all over the phone.

In addition, the security provided is not as strong as it could be, because consumer devices like phones have a bias toward openness. Security technologist Bruce Schneier, who is the author of the Schneier on Security blog, says there are two kinds of errors a security system can make: a false positive that lets the wrong person in, and a false negative that keeps the right person out. "You can fine-tune the balance between the error rates," says Schneier, but most consumer-oriented biometric systems will be set to err on the side of false positives. "A burglar tries to get in your house only occasionally, but you need to get in twice a day," he says, adding that, if your home security system regularly locks you out, you simply will not use it, even though it would also block the rare burglar.

Says Meyer, "Generally speaking, a knowledge-based security method such as a passcode is stronger than a biometric one." However, according to a 2013 global survey by McAfee and One Poll, more than a third of mobile phone owners do not even bother to use a PIN or password at all; of those that do, more than half have shared the details with others.

"Apple and Samsung aren’t targeting people with serious security needs," Meyer says. "They’re targeting the average user who isn’t already using authentication. For those people, a fingerprint reader is a real boon."

In other words, a weak security method that is actually used is better than a strong method that is not.

Logan Kugler is a freelance technology writer based in Clearwater, FL. He has written for over 60 major publications.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment