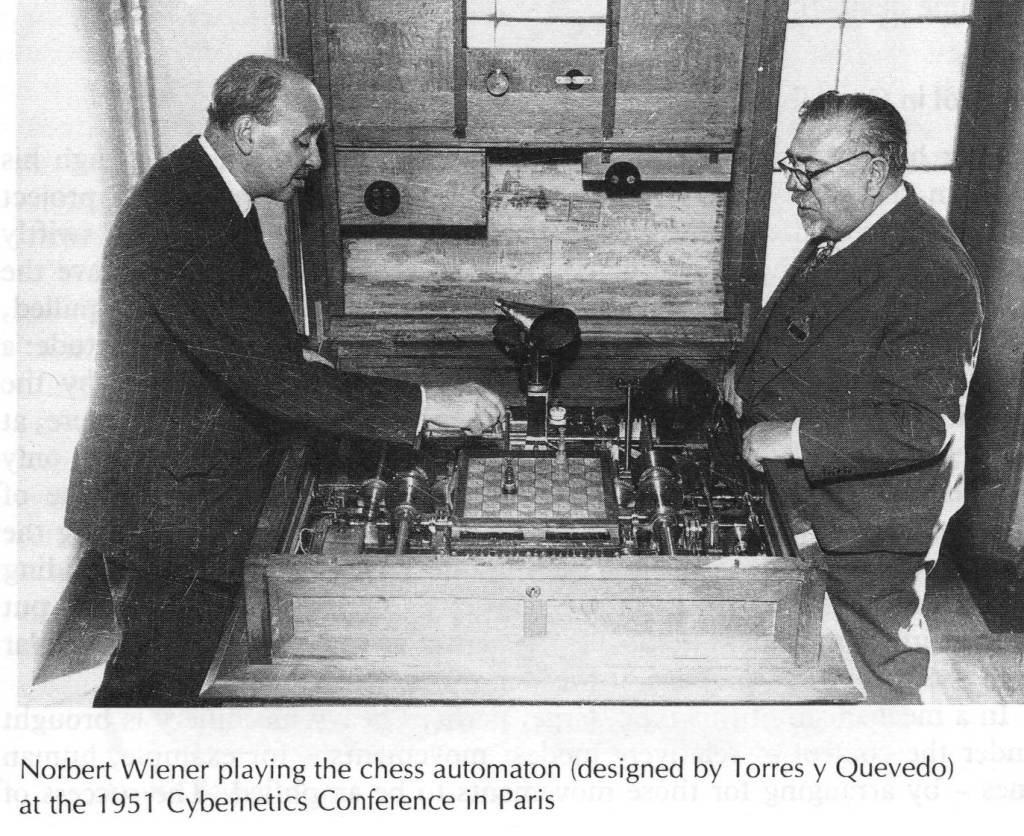

For a long time, chess was considered the epitome of the human mind, a touchstone for artificial intelligence. Alan Turing had already dealt with this topic. In 1770, Wolfgang von Kempelen built the chess-playing Turk, in 1912 Leonardo Torres y Quevedo created an end-game machine, and in 1951 Norbert Wiener played against Torres y Quevedo’s machine in Paris. In 1997, Garry Kasparov lost in New York to IBM’s Deep Blue chess-playing computer.

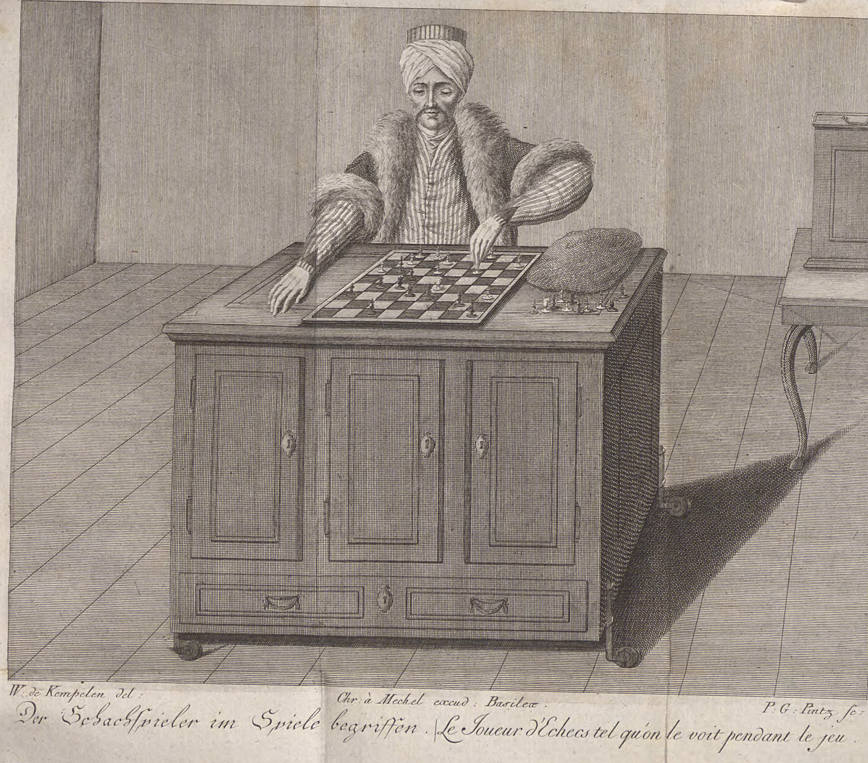

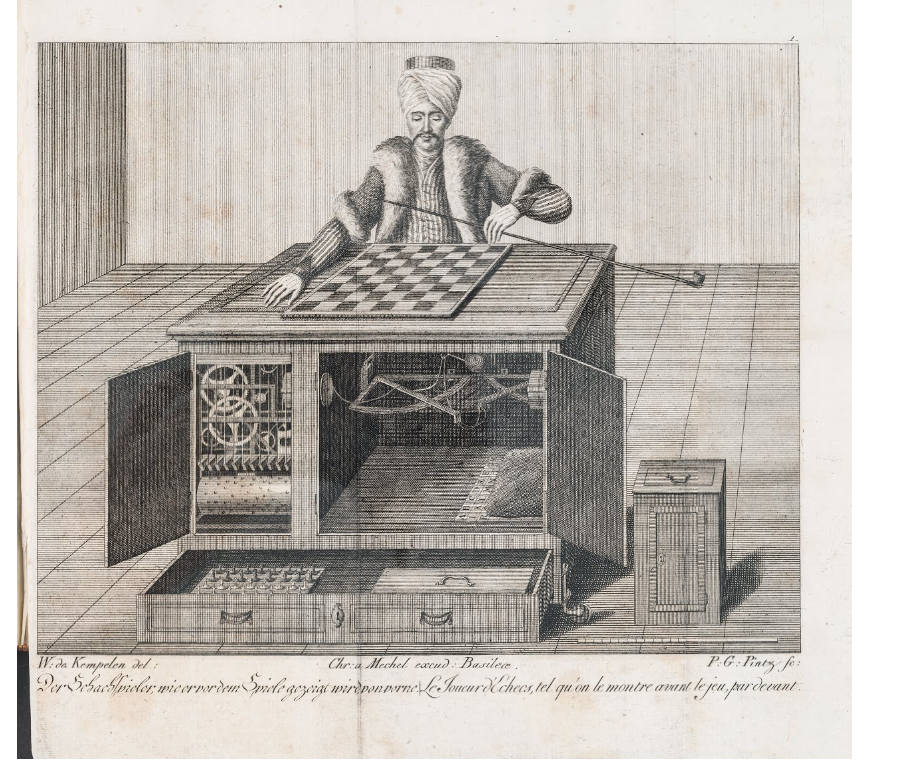

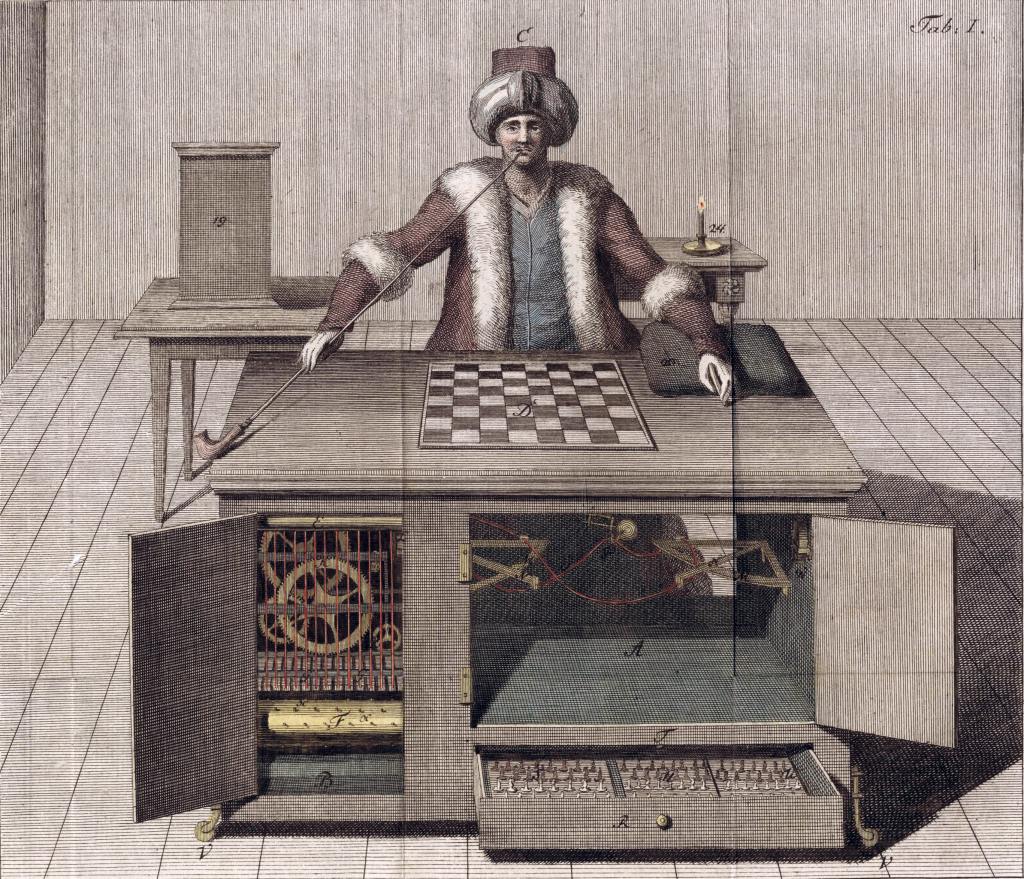

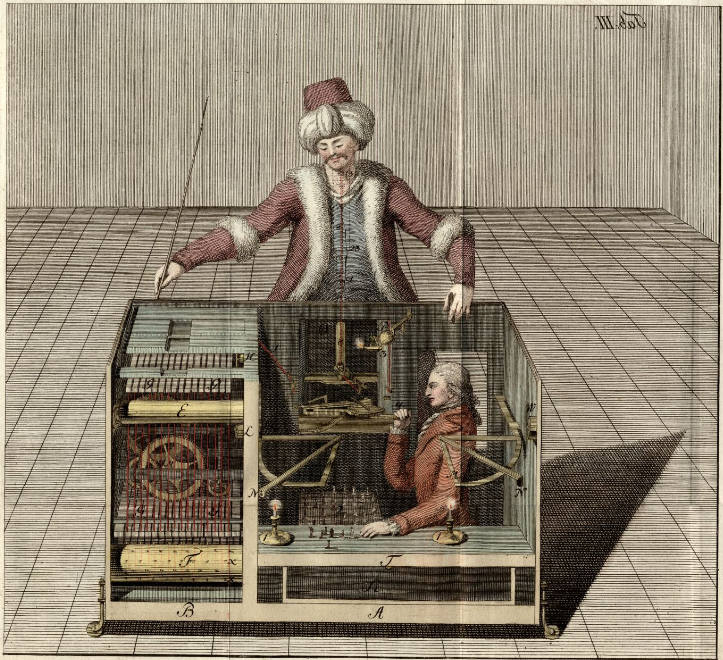

The mechanical Turk, a fake automaton

In the 18th century, Wolfgang von Kempelen’s victorious mechanical Turk (1770) amazed the world, see Figs.1-4. However, there was a person hidden inside. Charles Babbage is said to have lost a game against the fake automaton in 1819, similar to Napoleon.

Source: Karl Gottlieb von Windisch; Christian von Mechel: Karl Gottlieb von Windisch’s Briefe über den Schachspieler des Hrn. von Kempelen nebst drey Kupferstichen, die diese berühmte Maschine vorstellen, Basel 1783

Source: Karl Gottlieb von Windisch; Christian von Mechel: Karl Gottlieb von Windisch’s Briefe über den Schachspieler des Hrn. von Kempelen nebst drey Kupferstichen, die diese berühmte Maschine vorstellen, Basel 1783

Source: Joseph Friedrich Freyherr zu Racknitz,: Über den Schachspieler des Herrn von Kempelen und dessen Nachbildung, Joh. Gottl. Immanuel Breitkopf, Leipzig und Dresden 1789

Source: Joseph Friedrich Freyherr zu Racknitz: Über den Schachspieler des Herrn von Kempelen und dessen Nachbildung, Joh. Gottl. Immanuel Breitkopf, Leipzig und Dresden 1789

There is a functional replica of the mechanical Turk in the Heinz Nixdorf Museum Forum in Paderborn, see Fig.5.

End-game machine by Torres y Quevedo

The Spanish engineer Leonardo Torres y Quevedo, who built a cable car over Niagara Falls, also created two chess-playing machines called El ajedrecista (chess player). The first, from 1912, was demonstrated in Paris in 1914. The machine plays with a king and rook (white) against a king (black). The second model was designed in 1920, see Fig.6. Both machines have survived and are located in Madrid.

Credit: Museo Leonardo Torres Quevedo, Escuela tecnica superior de ingenieros de caminos, canales y puertos. Universidad politecnica de Madrid.

At the Paris conference “Les machines à calculer et la pensée humaine” in 1951, the U.S. cyberneticist Norbert Wiener played against the second version of this machine, see Fig.7.

Credit: Studio Constantin, Paris.

First World Microcomputer Chess Championship in London in 1980

In 1980, the first World Microcomputer Chess Championship took place in London, see:

WMCCC 1980: https://www.chessprogramming.org/index.php?title=WMCCC_1980,

World Microcomputer Chess Championships: https://www.chessprogramming.org/World_Microcomputer_Chess_Championship,

1st WMCCC London 1980: https://www.schach-computer.info/wiki/index.php?title=1._WMCCC_London_1980.

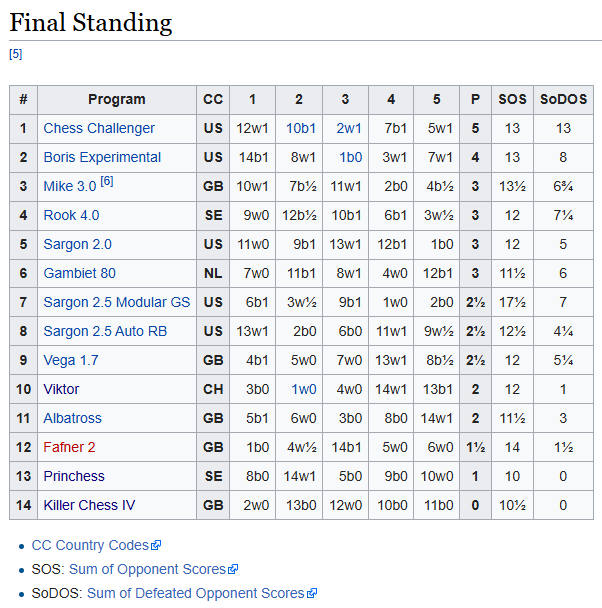

The organizer was the famous British international chess master David Levy. I took part with “Viktor,” a program developed by the Privates Forschungsinstitut für Androidentechnik (Pfiat) in Darmstadt. I had examined the computer, named in honor of the long-time vice world champion Viktor Kortschnoi, on behalf of the Siemens-Nixdorf company. Thanks to a complex qualification, the program was admitted to the tournament. The Russian grandmaster Kortschoi was living in exile in Switzerland at the time. The championship was dramatic. Viktor beat the queen of the program that would later become world champion, but then collapsed, probably due to overheating. Re-entering the position took a lot of time, so that Viktor ended up in 10th place (out of 14), see Fig.8.

“The First World Microcomputer Chess Championship took place from September 04, 1980 to September 09, 1980, Cunard International Hotel, London, United Kingdom. This event is also known as the 3rd PCW Microcomputer Chess Championship or Personal Computer World Exhibition, also the unofficial 1st European Microcomputer Chess Championship. Being held under the auspices of the ICCA and FIDE, multiple entries from the same authors were possible. Dan and Kathe Spracklen had five Sargon versions running in various computers: Chess Challenger, Boris Experimental, Sargon 2.0, Sargon 2.5 Modular GS, and Sargon 2.5 Auto RB. Affiliated with Fidelity Electronics, they were the primary authors of the winning entity, Chess Challenger. Remarkably, Chess Challenger won games in its last three rounds versus three other Sargon programs, and was quite lucky as already in round 2 versus Viktor.”

Source: WMCCC 1980 – Chessprogramming wiki

Source: WMCCC 1980 – Chessprogramming wik

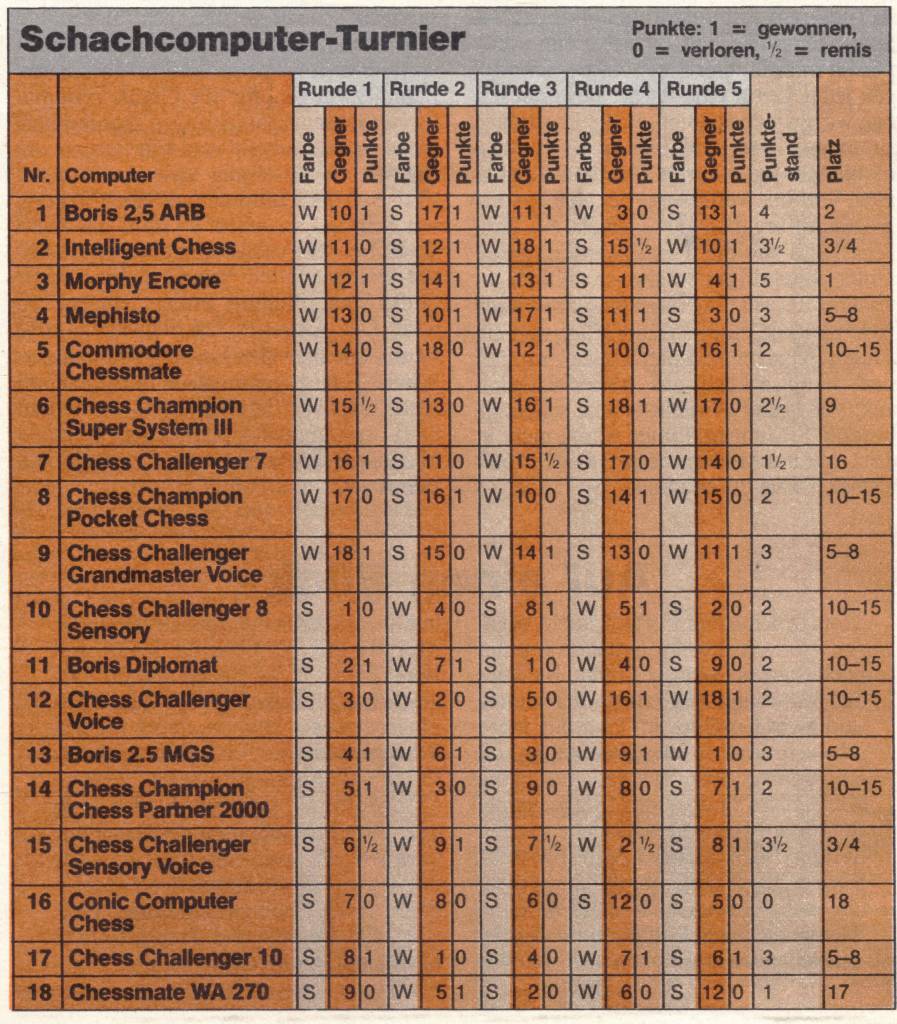

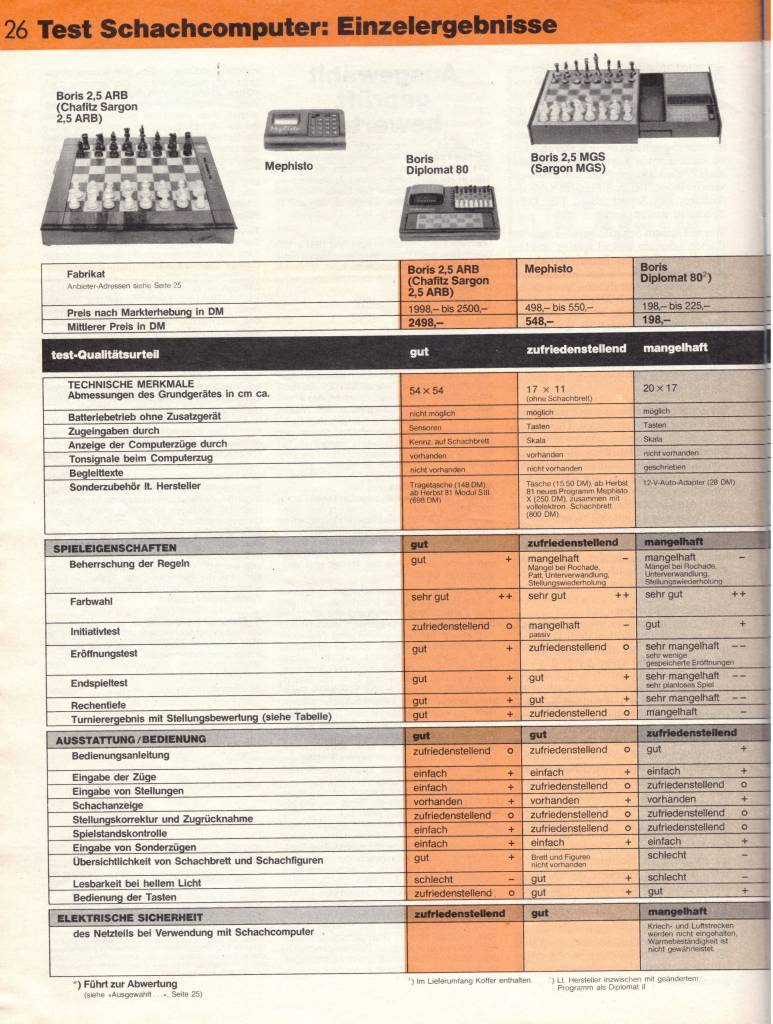

Gold rush

At that time, there was a gold rush for chess-playing computers. Many manufacturers were hoping for high profits. I subsequently examined all of the 20 or more devices available on the market for Stiftung Warentest in Berlin. The large comparison test was published in Test magazine (volume 16, no. 8, August 1981, pages 22–29), see Fig.9 (overview) and Fig.10 (results, 1 of 6 pages).

Source: Stiftung Warentest (ed.): Test Schachcomputer. Fast alle mattgesetzt, in: test, volume 16, no. 8, August 1981, page 23

Source: Stiftung Warentest (ed.): Test Schachcomputer. Fast alle mattgesetzt, in: test, volume 16, no. 8, August 1981, page 26

Kasparov’s defeat in 1997

Modern chess-playing programs are so strong that even top players can hardly keep up, see Fig.11. The tide turned with the defeat of the then world chess champion Garry Kasparov against IBM’s Deep Blue chess-playing computer in 1997. The game program AlphaGo from Google subsidiary DeepMind also came out on top versus a human Go champion.

Credit: Laurence Kesterson, Corbis/Sygma, Computer History Museum, Mountain View, CA

This post is the fifth in a series that presents selected technical marvels from the fields of computing technology, mathematics, astronomy, surveying, time measurement, looms, and automatons (automaton figures, chess-playing machines, musical automatons, automaton writers, drawing automatons, automaton clocks, picture clocks, globes, and historical robots). The examples are largely from the 15th to 20th centuries and do not claim to be exhaustive. In particular, artifacts are included for which high-quality illustrations are available. Most of the objects come from Europe, with a few from Africa, America, Asia, and Australia. The order is predominantly chronological. Famous names such as Archimedes, Hipparchus, Heron of Alexandria, Leonardo da Vinci, Galileo Galilei, John Napier, Jost Bürgi, Blaise Pascal, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, and Charles Babbage are associated with these works. In some cases, however, the inventors are unknown (e.g. abacus, Antikythera Mechanism, yupana, quipu); see Technical Marvels, Part 4: Leonardo da Vinci’s Robots – Communications of the ACM.

Further Reading

Bruderer, Herbert; Faller Kurt: Computer-Schach, in: Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 6 June 1979, page 67, https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000167775

Bruderer, Herbert: Nichtnumerische Datenverarbeitung. Dialogfähige Datenbanken und Informationsnetze, Computerschach und maschinenunterstützte Sprachübersetzung, Automation in Bibliotheken, künstliche Intelligenz und Computerkunst, Datenverarbeitung in Medizin und Chemie, Simulation von Entscheidungsprozessen, Rechtsinformatik. Bibliographisches Institut & F. A. Brockhaus AG, Wissenschaftsverlag, Mannheim, Leipzig, Wien, Zürich 1980, 267 pages, 60 figures

Bruderer, Herbert: AI began in 1912, 2020, AI Began in 1912 | BLOG@CACM | Communications of the ACM

Bruderer, Herbert: Die künstliche Intelligenz begann 1912 mit dem Schachautomaten von Torres Quevedo, https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000387462

Bruderer, Herbert: The birth of artificial intelligence. First conference on artificial intelligence in Paris in 1951?, in: Arthur Tatnall; Christopher Leslie (ed.): International communities of invention and innovation, IFIP WG 9.7 International conference on the history of computing, HC 2016, Brooklyn, New York, 25–29 May 2016, revised selected papers, Springer international publishing AG Switzerland, Cham 2016, pages 181–185

Bruderer, Herbert: Meilensteine der Rechentechnik, De Gruyter Oldenbourg, Berlin/Boston, 3rd edition 2020, volume 1, 970 pages, 577 figures, 114 tables, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110669664

Bruderer, Herbert: Meilensteine der Rechentechnik, De Gruyter Oldenbourg, Berlin/Boston, 3rd edition 2020, volume 2, 1055 pages, 138 figures, 37 tables, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110669671

Bruderer, Herbert: Milestones in Analog and Digital Computing, Springer Nature Switzerland AG, Cham, 3rd edition 2020, 2 volumes, 2113 pages, 715 illustrations, 151 tables, translated from the German by Dr John McMinn, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-40974-6

Ebert, Johann Jacob: Nachricht von dem berühmten Schachspieler und der Sprachmaschine des K.K. Hofkammerraths Herrn von Kempelen, Johann Gottfried Müllersche Buchhandlung, Leipzig 1785, 68 pages

Engélibert, Jean-Paul (ed.): L’homme fabriqué. Récits de la création de l’homme par l’homme, Editions Garnier, Paris 2000, 1184 pages

HNF Heinz Nixdorf MuseumsForum GmbH (ed.): Geschichte der Zunkunft. Eine Reise durch das HNF, Paderborn, 2nd revised edition 2023 268 pages

Pérès, Joseph (ed.): Les machines a calculer et la pensee humaine, Paris, 8–13 janvier 1951, Colloques internationaux du Centre national de la recherche scientifique, no. 37, Editions du Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), Paris 1953, xix, 570 pages

Hindenburg, Carl Friedrich: Über den Schachspieler des Herrn von Kempelen, Johann Gottfried Müllersche Buchhandlung, Leipzig 1784, 56 pages

Racknitz, Joseph Friedrich Freyherr zu: Über den Schachspieler des Herrn von Kempelen und dessen Nachbildung, Joh. Gottl. Immanuel Breitkopf, Leipzig und Dresden 1789, 69 pages

Richter, Siegfried: Wunderbares Menschenwerk. Aus der Geschichte der mechanischen Automaten, Edition Leipzig 1989, 164 pages

Standage, Tom: Der Türke. Die Geschichte des ersten Schachautomaten und seiner abenteuerlichen Reise um die Welt, Campus Verlag, Frankfurt, New York 2002, 224 pages

Stiftung Warentest (ed.): Test Schachcomputer. Fast alle mattgesetzt, in: test, 16th volume, no. 8, August 1981, pages 22–29

Torres-Quevedo, Gonzales: Présentation des appareils de Leonardo Torres-Quevedo, in: Joseph Pérès (ed.): Les machines à calculer et la pensée humaine, Paris, 8–13 janvier 1951, Colloques internationaux du Centre national de la recherche scientifique, no. 37, Editions du Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), Paris 1953, pages 383–406

Turing, Alan Mathison: Chess, in: Brian Jack Copeland (ed.): The essential Turing. Seminal writings in computing, logic, philosophy, artificial intelligence, and artificial life, plus the secrets of Enigma, Clarendon Press, Oxford 2004, pages 569–575 (1953)

von Muldau, Hans H.: Mensch und Roboter, Verlag Herder KG, Freiburg im Breisgau, Basel 1975, 192 pages

von Windisch, Carl Gottlieb: Inanimate reason; or a circumstantial account of that astonishing piece of mechanism, M. de Kempelen’s chess-player; now exhibiting at No. 8, Savile-Row, Burlington Gardens; illustrated with three copper-plates, exhibiting this celebrated automaton in different points of view, S. Bladon, No. 13, Pater-Noster-Row, London 1784, 58 pages

von Windisch, Karl Gottlieb; von Mechel, Christian: Karl Gottlieb von Windisch’s Briefe über den Schachspieler des Hrn. von Kempelen nebst drey Kupferstichen, die diese berühmte Maschine vorstellen, Basel 1783, 52 pages

Herbert Bruderer is a retired lecturer in the Department of Computer Science at ETH Zurich and a historian of technology. He recently was added to the Honor Roll of the IT History Society.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment