At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, many employees were sent home. Thanks to the Internet, telecommunication tools, and cloud-based software repositories, software developers could continue to work efficiently under these trying circumstances. Post-pandemic, many software developers have continued to work remotely.

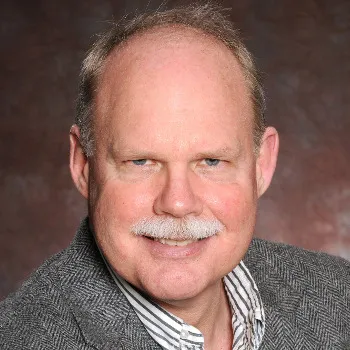

But remote software development did not begin in March 2020. Over 50 years earlier, in 1969, Marjorie (Marge) Hoogeboom began working remotely as a computer programmer for General Electric (GE), making her one of the world’s first—perhaps the first—remote software developers. Marge passed away on August 11 at the age of 82, but it was my privilege to interview her beforehand; what follows is a summary of her story, condensed from the full interview.

Marge was born in Grand Rapids, Mi, in 1943; she grew up in the Cold War aftermath of World War II, when the U.S. government was emphasizing education in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). As a 1950s high school student, Marge was good at math and, while reading about computers sparked her curiosity about them, she had no means of accessing one. After graduating from high school in 1960, she enrolled at Calvin College (now Calvin University); at that time, Calvin offered no computing courses, so Marge majored in mathematics.

At Calvin, Marge met Tom, a chemistry major who was two years older and the two began dating. After Calvin, Tom planned to pursue graduate study at Purdue University, so when the two decided to marry in 1963, Marge transferred to Purdue. The previous year, Purdue had launched the first U.S. computer science department; Marge took as many of its courses as she could, which provided her with the opportunity to learn FORTRAN, COBOL, assembly, and other programming languages. She proved to be a talented programmer and graduated from Purdue in January 1965.

After Tom finished at Purdue, General Electric (GE) hired him as a research chemist at their R&D center in Schenectady, N.Y. The couple now had an infant daughter and Marge planned to stay at home with her. But GE had a contract to build the operating system (OS) for a Honeywell mainframe computer and was struggling to find people who could program—they were giving logic tests to all their employees in hopes of finding capable people. When GE learned that Marge knew multiple programming languages, including an assembly language like that of the Honeywell, they offered her a full-time job. But she only wanted to work part-time, so after some negotiation, GE agreed to a half-time programming position.

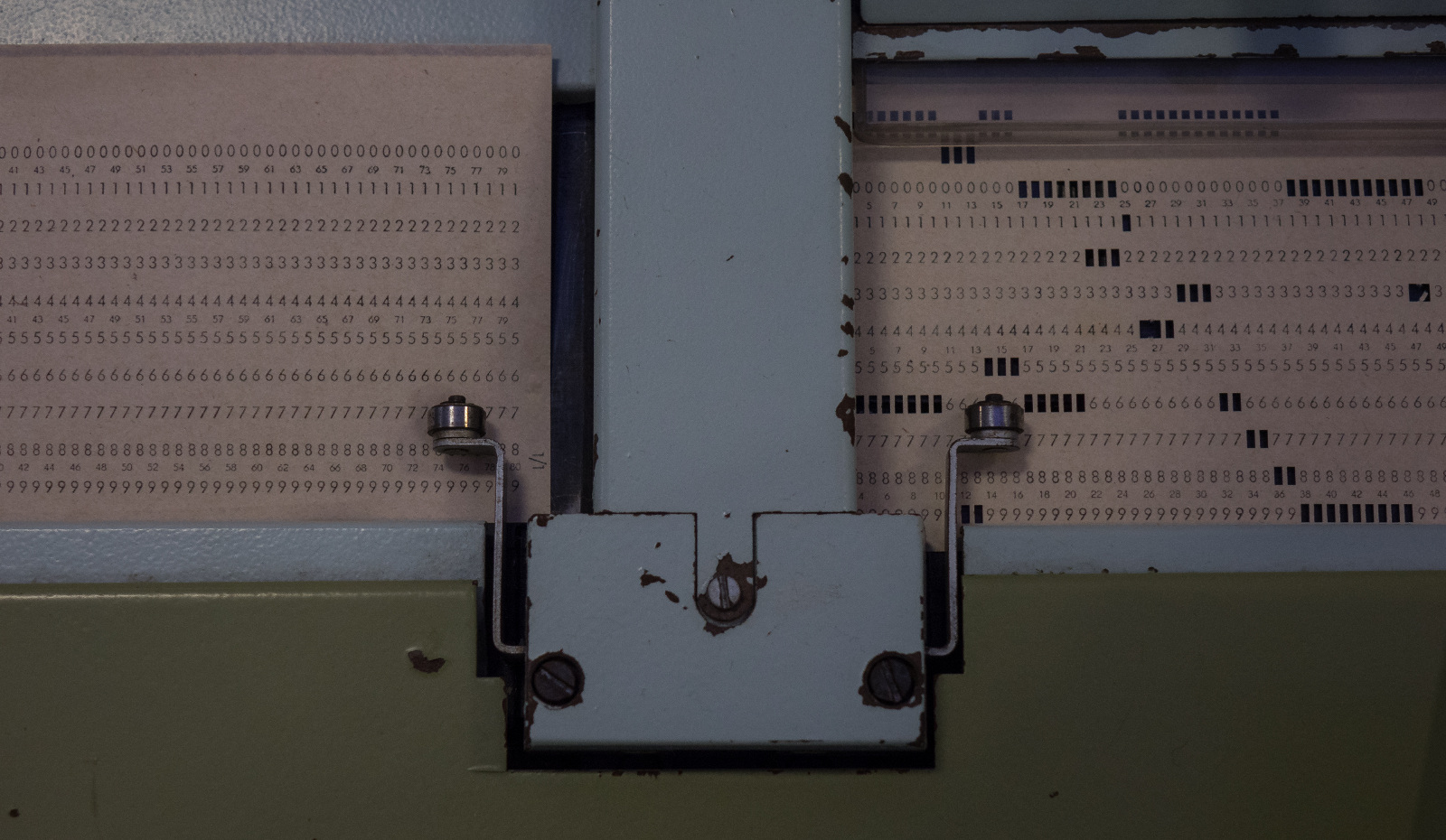

When Marge was hired in 1965, ‘programming’ consisted of: (i) using flow-charts and other tools to develop the step-by-step logic needed to solve a problem, (ii) using paper ‘code sheets’ to express that logic in a programming language, and then (iii) using a keypunch to punch the lines of code onto Hollerith cards.

A ‘source program’ was a tangible stack of these punch-cards; a mainframe computer could use a card reader device to read such a program into its main memory, and then use a compiler to translate that program into a machine language version that the computer could run. By the late 1960s, GE had streamlined this process, replacing the punch cards and card readers with ‘terminals’—basically keyboard input devices plus paper-teletype output devices—connected to the mainframe. Using a terminal, a programmer could interact with the mainframe more directly: edit a program’s source code (one line at a time), translate a source program into machine language, run the machine language version of the program, and so on.

Back to our story: In 1969, GE transferred Tom to its plastics plant in Mt. Vernon, IN. This location had no computer and since the couple now had a second daughter, Marge planned to quit work and stay at home with the children. But at her send-off party in New York, her boss said how much they were going to miss her—that working half-time, she had been more productive than any of their full-time employees! Marge jokingly told her boss that if he wanted her to stay on, GE could always install a terminal in their house in Indiana. That seemed absurd, so the conversation shifted to other topics. But later, her boss came back to her and asked, “Would you really be open to that?” and Marge said, “Sure.” So, after she and Tom were settled in Indiana, GE provided a modem-equipped Teletype Model 32 ASR terminal for their house and paid to set up a dedicated phone line between it and GE’s New York mainframe, over 1,000 miles away.

Building the dedicated connection required the Hoogeboom’s Indiana phone company to install seven miles of two-wire copper cable for the terminal. The company didn’t have enough of this specialized wire locally, so most of it had to be brought in from other counties.

In 1969, the Internet was many years away, so Marge and her boss had to invent a new workflow for her to work remotely: each weekend, GE would ship her a package containing paper-listings of parts of the OS source code with unresolved issues. The next week, she would use those listings to find the issues, develop solutions for them, and then use her home terminal to fix the source code. At the end of the week, she would issue a special command at her terminal. On receiving this command, the New York office would merge her changes into the OS, run tests, generate new listings for its remaining issues, and ship them to her, starting the next week’s workflow.

Credit: Marge Hoogeboom

And so, Marge Hoogeboom became a remote software development pioneer. She continued to work remotely for GE for several years, and only stepped down when she thought doing so might save a co-worker’s job.

But this was just the beginning of her career as a computing professional. In the 1970s, she worked for Mead-Johnson helping design and build a corporate intranet connecting their Indiana and Arizona mainframes. (For reference: TCP/IP was not adopted as an ARPANET standard until 1983.) In the early 1980s, she got to know and became friends with Grace Hopper; in 1989, she received the ‘William J. Upjohn Prize’ as Upjohn’s outstanding employee. During the 1990s, she (assisted by her husband) developed a database to organize and streamline relief efforts for victims of natural disasters.

This is just a brief overview of Marge’s story. For more details, please see the full interview.

Additional insights into Marge’s life are provided in her obituary; this talented, generous, pioneering problem-solver will be sorely missed by friends and family.

Joel C. Adams is an emeritus professor of computer science at Calvin University.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment