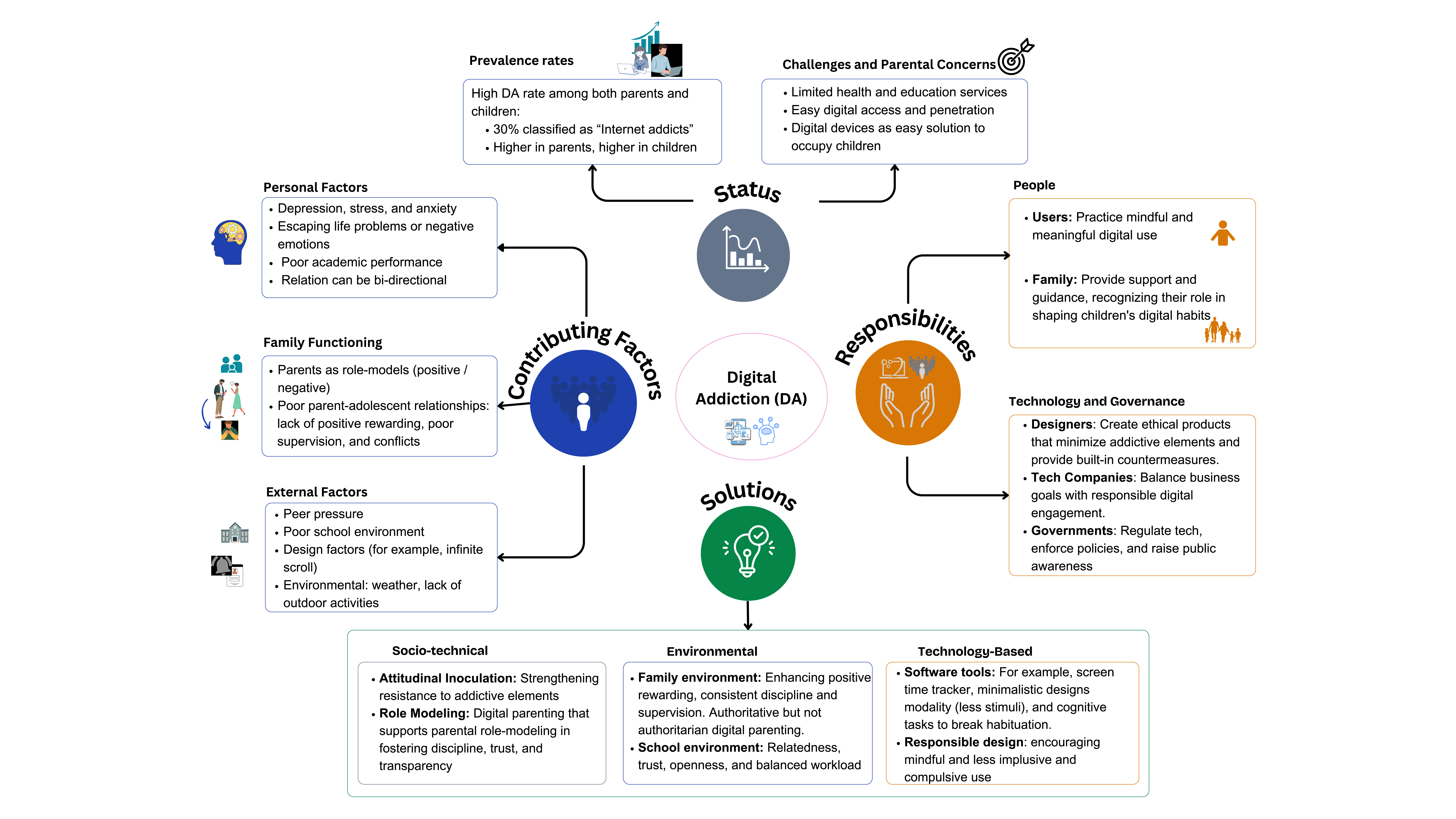

Digital addiction (DA) refers to a problematic relationship with technology characterized by symptoms of behavioral addiction, including mood modification, salience, tolerance, conflict, withdrawal symptoms, and relapse. While addictive use of technology is not yet officially recognized as a clinical diagnosis, certain forms, such as Internet gaming disorder (IGD), have been classified as clinical conditions. Notably, IGD was included in the ICD-11 (International Classification of Diseases) by the World Health Organization in 2018.19 Despite that, public concerns about technology overuse and dependence continue to rise, though they vary in intensity across different regional and cultural contexts. In this article, we discuss DA in the Arab countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) region. Figure 1 summarizes the article’s key points, outlining DA status; key contributing factors; the roles of families, schools, and policymakers; and potential solutions and intervention strategies.

Status

In three major studies we conducted among families in the Arab GCC region, we found high prevalence rates of DA among both parents and children. To measure it, we used the conceptualization and scale provided by Young’s Internet Addiction Questionnaire. That test is based on the behavioral addiction criteria outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and focuses on user behavior rather than the characteristics of digital technology itself. It remains relevant and has been widely validated and used across various populations, including in the Arab region.17 Approximately 30% of both parents and adolescents met the criteria for being classified as “Internet addicts.”5,13,14 A systematic review and meta-analysis also confirmed the high prevalence of Internet addiction in the GCC, estimating it at 33%.2 This pattern is reflected in cross-cultural comparisons, where Arab samples from the GCC scored more than twice as high as their counterparts in Italy and Greece.21 Additionally, research indicates that Internet addiction is more prevalent among females (48%) than males (24%) in the GCC region,2 though this may depend on the type of online activity, with males showing higher online gaming activity and females having higher social media use.

The notably high prevalence rate of DA in the GCC region may be attributed to several factors, including the hot climate and limited availability of outdoor activities, as well as the high levels of digital penetration and widespread access to the Internet and digital devices. Additionally, busy lifestyles often lead parents to rely on digital devices as an easy way to keep their children occupied. This pattern of reliance has raised concerns, with children’s social media consumption being compared to consuming junk food.10

Parents surveyed expressed concerns about the availability of services and effective approaches to address the issue when it arises in their households. Existing services often treat digital addiction as a general behavioral issue, using approaches that lack specialization and overlook the unique characteristics of technology-related behaviors.11 For example, advice to reduce exposure is often implemented through applications that block specific sites, filter content, or limit screen time. However, these measures are frequently impractical and easily circumvented. In addition, users’ intentions behind technology use can vary, which affects what should be considered addictive use,8 making it difficult to determine what to filter or restrict.

Contributing Factors

There is increasing evidence that excessive and obsessive technology use is prevalent in many societies and, under certain conditions, can lead to negative life experiences. The harm spans multiple facets, including academic and job performance, sleep quality, dietary habits, emotional well-being, family relationships, personal development, privacy concerns, and social interactions.12,16 However, we argue that while DA can facilitate and lead to such negative outcomes, it can also coexist with or even result from them. Digital addiction may develop from reliance on digital technology as a coping strategy or as an escape into an alternative reality. It can stem from underlying issues such as depression, stress, and anxiety, with family and school environments acting as mediating factors. A positive family and school environment can significantly reduce the likelihood of developing an obsessive relationship with technology by compensating for negative emotions and mitigating their impact.9 Similarly, DA may have a cyclical relationship with school pressure and poor academic performance, where each can reinforce and exacerbate the other. In such contexts, a supportive family environment can help mitigate the use of the Internet as an escape mechanism.15

Another set of reasons relates to parents and their technology-usage behavior. Parental DA levels were found to correlate with their children’s DA levels, both in overall DA scores and in specific symptoms associated with DA.5,13 A positive family environment, characterized by positive rewards, consistent discipline, and supervision, was associated with lower levels of Internet addiction in children.20

Other reasons for DA may include environmental factors, such as peer pressure to remain online and responsive, as well as perceived social norms around online activity.7 Research also suggests that individuals who primarily engage with digital platforms for entertainment rather than for information-seeking are more likely to exhibit addictive usage patterns, as observed among adolescents in Jordan and Lebanon.6,18 Additionally, it has been argued that social media design contributes to problematic experiences such as fear of missing out (FoMO) and procrastination.1,7 These designs often incorporate persuasive and attention-grabbing techniques commonly used in marketing and gaming, which increase user engagement and make it more difficult to disconnect. Examples include the infinite scroll and pull-to-refresh mechanisms, which leverage the principle of variable ratio rewards, as well as features that provide social validation and reassurance. While such dynamics also occur in real life, the constant availability and accessibility of these elements on social media amplify users’ attachment, intensifying it to a significantly heightened level.

Responsibilities and Solutions

Addressing DA requires shared responsibility.3 Parents, through supervision and role modeling, help shape children’s digital habits.20 Schools also play a role in shaping behavior through supportive environments and, potentially, through targeted awareness programs.9,15 Policymakers provide the frameworks and directives necessary for building the infrastructure and systems required to enable large-scale impact.

Solutions to DA can take various forms, including psychosocial approaches such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, software-based tools like digital nudges and usage monitoring apps, and supportive interventions, which may include medication for mental health concerns commonly associated with digital addiction, such as depression.11 However, research exploring and evaluating such interventions remains limited.11 An innovative solution grounded in attitudinal inoculation theory showed promising potential.4 This approach involves challenging adolescents’ assumptions about their understanding of how digital media captures their attention and whether they can recognize that and recommend solutions to others. Through sessions and quizzes, this method aims to enhance epistemic cognition and build immunity to persuasion and immersive elements in digital spaces. Additionally, the principle of role modeling, where parents demonstrate discipline, openness, trust, and transparency in their digital use and general behavior, may be more effective than simply educating children or giving advice. Children are more likely to mimic their parents’ behavior, making positive parental behavior a powerful contagious influence.20 Solutions should therefore be holistic and sociotechnical, focusing on the broader environment rather than solely on individual problematic behaviors.

Acknowledgments

This publication was partly supported by NPRP 14 Cluster grant # NPRP 14C-0916–210015 from the Qatar National Research Fund (a member of Qatar Foundation). The findings herein reflect the work and are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment