Federal investment in research has consistently served as the bedrock of American innovation, driving scientific breakthroughs, fostering economic growth, and enhancing national security. This is particularly evident in the field of computing, where foundational government funding has translated into transformative technologies and the rise of entirely new industries. Far from being a drain on public resources, these strategic investments act as a powerful catalyst, creating a virtuous cycle of discovery, application, and prosperity.9

One of the most compelling arguments for federal research funding lies in its ability to support basic, high-risk, long-term research the private sector is often unwilling or unable to undertake. Companies, driven by quarterly profits and immediate returns, typically prioritize applied research with clear commercial applications.10 However, truly revolutionary advancements often emerge from fundamental inquiries into the unknown, without a predefined path to market. It is here that federal agencies, such as the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and the National Science Foundation (NSF), step in, providing the crucial early-stage capital for exploration.3

The birth of the Internet is a prime example of this principle in action. In the late 1960s, DARPA initiated the ARPANET project, a groundbreaking effort to create a robust, distributed communication network that could withstand an attack.8 This initial investment in packet-switching technology and network protocols, driven by national security concerns, laid the groundwork for what would become the global Internet.1 Subsequent federal funding through the NSFNET in the 1980s further expanded the network, connecting universities and research institutions across the nation and eventually paving the way for commercialization.5 Similarly, much of the early work that led to the World Wide Web occurred at national laboratories funded by the Department of Energy and at NSF supercomputer centers. Without this sustained federal commitment, the Internet as we know it today, along with the multi-trillion-dollar digital economy it enables, would simply not exist. Companies such as Cisco, Google, Amazon, and countless others owe their very existence to these foundational, federally funded endeavors. More recently, researchers developed the concept of software-defined networks allowing the Internet to further scale, while supporting new functionality and enhancing reliability.

Federal research has often been the initial source of support for many innovations in computing technology, including RISC architecture, the Google search algorithms, much of the work in artificial intelligence (including the creation of deep neural networks and their training and inference algorithms), advances in compiler technology, graphics-processing engines, signal-processing algorithms that enabled Wi-Fi, multiprocessor architectures, modern computational algorithms, programming-language advances, and many more. This collection of original articles can only cover a few of the many information-technology revisions that originated with federal research funding.

Moreover, federal investment in research extends beyond direct project funding to the cultivation of human capital.7 University research, heavily reliant on federal grants, serves as a vital training ground for the next generation of scientists, engineers, and innovators.13 Doctoral students and postdoctoral researchers, supported by these funds, gain invaluable experience and contribute directly to cutting-edge discoveries. This continuous pipeline of highly skilled talent is essential for maintaining America’s competitive edge in the global technology landscape. Unlike some other disciplines, the majority of Ph.D. graduates in computing and related fields go into industry after graduation. These Ph.D.s play a key role in advancing computing technology. Furthermore, a shortage of Ph.D. graduates has led to a shortage of academics, impacting the ability of our colleges and universities to meet the demand for undergraduate education in computer science.12 If federal funding for research is curtailed, as has been a concern in recent years, the reduction will impact both the pace of innovation and also risk a “brain drain” as top researchers seek opportunities elsewhere.11

The economic returns on federal research investments are consistently high, often estimated to be significantly greater than other forms of public spending.4 Basic research, though unpredictable in its immediate applications, generates knowledge spillovers that benefit the entire economy.6 New industries are born, existing ones are revolutionized, and productivity dramatically increases. Consider the impact of federally funded research in areas such as semiconductor technology, which underpins virtually all modern electronics, or the advancements in computational biology that have accelerated drug discovery and personalized medicine.14 These innovations, initially nurtured by public funds, eventually attract massive private investment, creating jobs and driving economic prosperity.

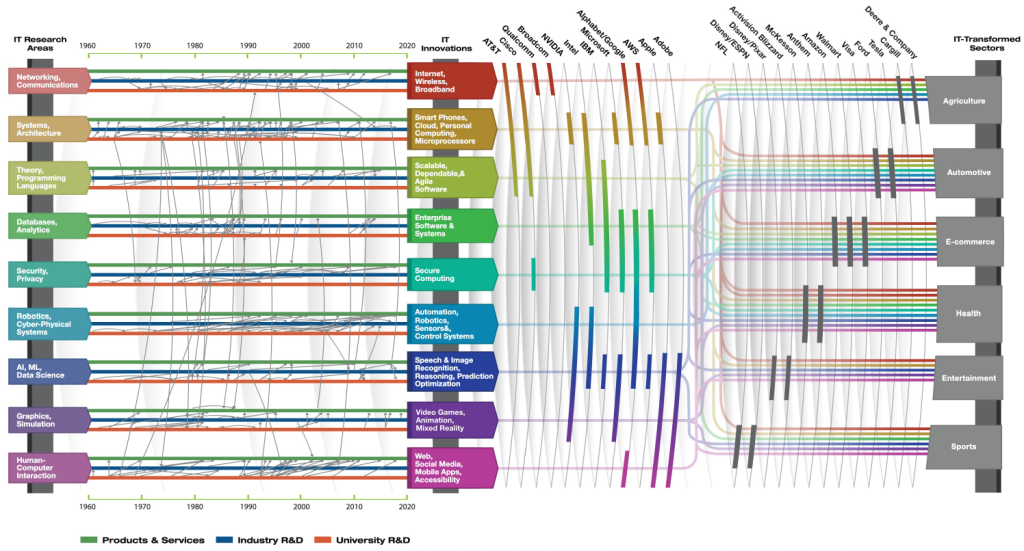

The figure illustrates how federal investments in universities lead to new commercial computing technologies. Technologies may originate in the university, be developed in industry R&D laboratories, and then influence further work at the universities, often spinning off major new products as the process progresses. Without the initial federal investment in university research, this virtuous cycle, which has dramatically enhanced U.S. economic competitiveness, would be in great danger. In an interview, Elizabeth Mynatt discusses this critical interaction and offers an ongoing examination of it.

Figure. Tire Tracks diagram shows the interaction of university research, industry R&D, and products in the development of major aspects of IT technology.11

Conclusion

Federal investment in research, particularly in the dynamic and rapidly evolving field of computing, is not merely an expenditure but a strategic imperative. It underwrites the fundamental inquiries that lead to transformative breakthroughs, provides the essential infrastructure for innovation, and cultivates the human talent necessary to push the boundaries of knowledge. The Internet, modern AI, and countless other technological marvels serve as undeniable testaments to the profound and enduring benefits of this governmental commitment. Sustained and robust federal funding for research is therefore not just about scientific progress; it is about securing America’s national and economic security.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment