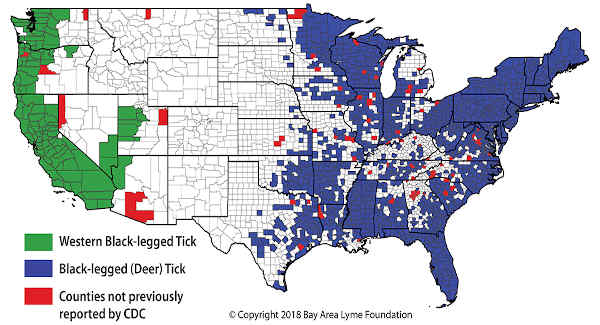

A novel partnership between researchers from two university laboratories and a Silicon Valley-based disease advocacy organization has demonstrated the potential power of “non-traditional” health data collection efforts, as citizen scientists nationwide found disease-bearing ticks in 83 counties nationwide they were not believed to inhabit.

The effort took just two years, while the researchers estimated traditional surveillance methodologies likely would have taken 30 years to yield the same results.

To a layperson, such results might sound revolutionary enough to become standard procedure. Yet Linda Giampa, executive director of the study’s sponsoring organization, the Bay Area Lyme Foundation, has long experience with the traditionally conservative epidemiology community and is cautiously optimistic at best.

“I have been doing this since 2013,” Giampa said. “My feeling is things have changed a bit over the years. We are working on three Big Data projects right now. Have any public health people contacted us? No. I tend to be an optimistic person, so I feel like maybe eventually they will.”

collected 20,000 disease-bearing ticks across the U.S. over a two-year span.

The study discovered ticks in 83 counties where their presence had previously not been reported.

Credit: Bay Area Lyme Foundation

Giampa’s optimism might be borne out more quickly than “eventually”; in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic and the social justice movement precipitated a new reckoning around hidden or unrecognized elements of disease and deprivation, and how they are connected. Efforts to address these things are in their infancy, but can be seen in academic research projects tying disparate elements together in new ways, such as the beginning of local public health departments’ efforts to emphasize wider data collection, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s (RWJF) $50-million pledge to create a more equitable and comprehensive public health data infrastructure.

‘Absolutely pivotal’

The RWJF funding was the culmination of a five-month-long deep dive into the current state of the public health data infrastructure by a blue-ribbon commission the foundation convened. Alonzo Plough, RWJF’s chief scientist, said the commission drew on its members’ years of experience in healthcare, along with research done by the Rand Corp. focusing on the public health ramifications of the pandemic and racial inequities.

“We aren’t collecting the right kind of data to understand those issues from a prevention standpoint,” Plough said. “Those dual crises were the backdrop for the foundation’s interest, and as a guy who practiced public health for 25 years, I know that data are the way to communicate with people. And if you are measuring the wrong things at the wrong time, you won’t create the best preventive response to anything.”

Perhaps the best-known example of what public health officials considered the “wrong things at the wrong time” was the widespread skepticism the epidemiological community showed for Google Flu Trends. The platform launched in 2008 as an attempt to predict the spread of the flu by using data from Google searches for terms such as “flu,” “fever,” and so on. It was widely considered a failure as a standalone prediction platform, but it also introduced the idea of including data, and lots of it, from non-traditional sources into the variables of public health. As a new generation of scientists began researching in universities, they took to these unorthodox approaches, while also ensuring their methodologies would be considered legitimate by public health officials. For example, Giampa said, the researchers behind the citizen science in the tick collection study, Nate Nieto of Northern Arizona University and Dan Salkeld of Colorado State University, were well known in the public health community.

“The academics driving the research wanted to use citizen science, but knew they would be questioned and poked at,” she said. “Nate and Dan were very well known and both on our scientific advisory board, and I think it was extremely important to have that credibility behind the institution.”

Giampa’s observations have been reinforced by several recently published studies that combined academic rigor and data well beyond the usual health data pools. One recent example is a neighborhood-scale exploration of the effects of air pollutant concentrations on disease burden in Alameda County, CA, led by researchers from George Washington University (GWU) and the Environmental Defense Fund. That study used data from monitors atop Google StreetView cars, high-resolution satellite images, and geographically granular disease data from the county’s public health department. Another, conducted by researchers at New York University (NYU), reviewed over 1,600 studies on machine learning and cardiovascular disease risk to better pinpoint how social determinants of health (SDOH) might be included in calculating risk for heart disease.

Pioneering public health departments also have taken advantage of the visibility the COVID pandemic presented by convincing their funders that better integrated data services can improve health at the collective and individual levels.

“Social determinants of health have really come to the forefront in terms of who has been most greatly impacted,” said Neetu Balram, public information officer for the Alameda County, CA, public health department. “COVID showed us how interconnected we are, but also that if you want to serve residents in a holistic way, it needs to be a multi-organizational effort.”

The collaboration between the department and the researchers who modeled the effects of air pollution concentrations could serve as a bellwether for contextualizing the crucial relationship between underlying disease rates and the addition of any new factor that may aggravate them. These factors are often the result of poverty, inadequate nutrition, and neighborhoods that are not conducive to healthy behaviors, and additional variables such as pollutants. One of the study’s key takeaways was that underlying disease burden could increase pollution-aggravated disease rates in neighborhoods where pollutant concentrations were not the highest.

“In the atmospheric sciences community, there’s a lot of focus on reducing pollutant exposure where those exposures are highest and that makes sense,” one of the study’s co-authors, GWU Ph.D. student Veronica Southerland, said. “But when you actually model the health burden associated with those pollutants, it really has to do with where the underlying vulnerabilities of the community are. We combined the high-resolution air pollutant estimates with the high-resolution baseline disease rates, and only with that latter portion were we able to see where the actual disparities were.”

SDOH components ready for integration

Those with chronic cardiovascular disease are one of the populations most susceptible to environmental and social factors aggravating their conditions; connecting the dots between individual disease and neighborhood risk factors, though tantalizingly close, has not yet happened. Machine learning algorithms using routine clinical data have already been shown to be more accurate in predicting cardiovascular disease risk than risk calculators that rely on data from study cohorts. However, those algorithms also often lack the extra-clinical context that can indicate those most vulnerable, according to evidence found by the NYU researchers.

The review, published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, sifted through 1,600 articles, ultimately focusing on 48 peer-reviewed studies published in journals between 1995 and 2020.

The NYU team found including social determinants of health in machine learning models improved the ability to predict cardiovascular outcomes like rehospitalization, heart failure, and stroke. However, these models did not typically include the full list of community-level or environmental variables that are relevant to cardiovascular disease risk. Some studies did include factors such as income, marital status, social isolation, pollution, and health insurance, but only five studies considered environmental factors such as neighborhood walkability or proximity to grocery stores.

The study’s senior author, NYU associate professor of computer science, engineering, and biostatistics Rumi Chunara, said her observations of the incidence of heart disease in lower socioeconomic populations, along with her familiarity with the predictive properties of ML algorithms, led her to her hypothesis.

“Pulling these two threads together, I became familiar with a lot of the standard ways our physicians and healthcare systems compute our cardiovascular risk. A lot of these multi-level social factors don’t jibe with accepted clinical factors, and that is why we are interested in this.”

‘This is the moment’

Chunara noted that, while current standard implementations of many electronic health records (EHRs) do not include SDOH modules, they are being added in pioneering systems. One such system, Contra Costa County, CA’s CommunityConnect program, integrates SDOH factors for residents served by Medicaid, such as housing, food insecurity, and financial instability, into the county’s ccLink EHR system. According to a case study published by the California Healthcare Foundation, the county is exploring adding additional partners such as food banks, transport services, and other safety net providers to the system, which has been the foundation of the county health system’s data infrastructure since 2012.

In Alameda County, where supervising epidemiologist Matt Beyers assisted the researchers who wrote the pollutant concentration study, efforts started only recently to streamline the data acquisition process, but Beyers is no less eager to bring greater functionality to his department. In recent months, he said the department had brought on a half-time data scientist to work on COVID-related data, and got a year’s worth of funding for a full-time engineer to work on non-COVID data.

“We want to be able to respond more quickly and free up time from doing these ad hoc requests, so we can do more interesting studies and look at causal factors, rather than simply running things on Excel,” Beyers said.

RWJF’s Plough said efforts like those of the California counties illustrate the importance of taking a local approach and building on already established systems, rather than trying to solve underlying social issues with a generic template. Within the foundation’s programs alone, he said, local efforts such as the Data Across Systems for Health and Sentinel Communities programs are thriving.

“The ones that are thriving are very organic and they spring from the community,” he said. “It has to emerge from issues of great salience to the community.”

He specifically mentioned $10 million of new funding resulting from the commission report, which has been dedicated to building community-academic partnerships with historically black colleges and universities in the Gulf Coast region. That funding, he said, will address health inequities by connecting environmental risk data and public health data: “You have to do that, because all of that has to be connected.

“This is the moment to do this.”

Gregory Goth is an Oakville, CT-based writer who specializes in science and technology.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment