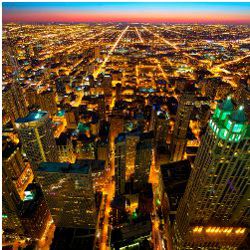

More than half of the world’s population currently lives in or around a city. By the year 2050, the United Nations projects another 2.5 billion people could be moving to metropolises. As urban populations increase, the number of data-generating sensors and Internet-connected devices will grow even faster. Experts say cities that capitalize on all the new urban data could become more efficient and more enjoyable places to live. The big question now is how to make that happen.

Until recently, this seemed to be as simple as choosing the right out-of-the-box smart city solution from a big multinational corporation. “The overhyped promises from the big technology companies have kind of blown away,” says Anthony Townsend, Senior Research Scientist at New York University’s Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management. “Now you have city governments regrouping and developing comprehensive long-range visions of the role information technology will play in making their city better.”

The leading urban centers are not placing their technological futures in the hands of a company or a single university research group. Instead, they are relying on a combination of academics, civic leaders, businesses, and individual citizens working together to create urban information systems that could benefit all these groups. The challenges are diverse and demanding, but a handful of new projects around the world are providing a glimpse of what a truly smart city could offer.

The Sensing City

In Chicago, Argonne National Laboratory computer scientist Charlie Catlett is leading a collaboration called the Array of Things, a planned citywide installation of at least 500 sensor-packed boxes. Catlett, who is also director of the Urban Center for Computation and Data, says the project began as an effort to better understand air quality downtown, but after conversations with city officials and other scientists, it expanded in scope.

The boxes will be approximately the height and width of a parking sign and attached to poles or other fixtures. Each unit will have 17 or 18 sensors, and although the final implementation has not been determined, the boxes will likely measure temperature, precipitation, humidity, air quality, and pedestrian flow. Microphones, for instance, could detect noise pollution or trucks idling in one spot for too long.

The data captured will be valuable to a variety of groups. Atmospheric scientists hoping to understand urban climate will have access to detailed information on air quality, temperature, and precipitation. Social scientists will be able to study pedestrian counts and flows to analyze how people move through urban spaces. City planners will be able to make more informed decisions about where to place new bus stops or how much road salt to apply to certain areas after a heavy snow. There is also the potential to use the data to fight gridlock. “The traffic controllers would like these on every corner,” Catlett says.

Average citizens will benefit as well. Today, a runner equipped with a smartphone or a wearable fitness device can easily track her route, mileage, average heart rate, and total steps; now, imagine that gadget talking to the city itself. The Array of Things units could exchange data each time a wearable device communicating via a Bluetooth or Wi-Fi signal comes within range. “Our phones can keep track of so much,” says Catlett, “but I’m not going to find out my exposure to particulate matter or carbon monoxide or ozone. This new device will tell me my exposure to various emissions; then, maybe I can use that to change my route or manage my exposure.”

The city of Glasgow, as part of a project called Future City Glasgow, is testing a similar technology: an installation of intelligent street lamps that will measure air quality, traffic, and pedestrian flow. Yet Glasgow is also depending on a broader range of sources to drive its transformation into a smarter metropolis. Recently, Glasgow announced the launch of its City Data Hub, a cloud-based, publicly accessible information store drawn from more than 400 datasets. The Hub provides data on traffic, pedestrian footfall in retail areas, parking spots at public garages, and more. Eventually, it could tap into other sources as well, such as smartcard readers at subway turnstiles. “We’re creating an ecosystem of data providers throughout the city,” says Colin Birchenall, the technology architect for Future City Glasgow.

Citizens First

In all these projects, organizers hope this ecosystem will include the citizens themselves. A city can only install so many smartlights or lamppost-mounted units, but almost every resident will be carrying a sensor-packed smartphone. Tapping into that data will provide a whole new layer of information. For citizens to volunteer this information, though, there has to be a clear value proposition.

As an example, Birchenall cites Glasgow’s new cycling app, which helps riders plan routes, easily locate bicycle racks, and more; the app requests the right to gather data on a user’s trips. There is no immediate benefit, but Birchenall says cyclists have opted in because of the potential long-term benefits. The idea is that if users do volunteer their data, then city planners will be better able to analyze cycling traffic, and potentially improve urban infrastructure by adding racks or widening lanes.

This approach is also behind certain aspects of the Quantified Community project, a collaboration between real estate developers, technology and design firms, and researchers at New York University’s Center for Urban Science and Progress (CUSP). As the developers revamp and rebuild several derelict city blocks in New York, CUSP researchers are working with them to install a range of smart systems. There will be sensors that operate on the large scale, tracking waste disposal and recycling, but the researchers also hope residents will play an active role as willing sources of data.

CUSP deputy director Constantine Kontokosta points to the installation of sensors that track energy and water consumption down to individual outlets and faucets. The data will be anonymized, and while residents will still be able to opt out, Kontokosta suspects this information will prove appealing. “The value is clear,” he says. “We’re saying that if you let us collect information about how much energy and water you’re consuming, then we will analyze the data, and we’ll tell you about others so you can gauge how you’re doing.” The residents might be inspired to change their behavior as a result, and perhaps use less water or energy.

The Quantified Community and the Array of Things projects hope to track pedestrian movement as well, but in both cases, the researchers have designed the systems to preserve privacy. If an Array of Things unit was measuring pedestrian flow, and you were to walk past with a Bluetooth-enabled smartphone, the device might register that signal, but it would not store the unique signature from your phone; instead, it would simply interpret that signal as the presence of a person and delete the private data, so there would be no record that you, specifically, were there. “Our plan is to count the number of unique addresses that we can see, then throw those addresses away and report only the count,” Catlett explains. “This is meant to be a public data utility, so we have to think hard about how to protect people’s privacy.”

Open Data, Endless Possibilities

This public utility approach is one of the common threads linking the different smart city projects. The Quantified Community project will publicly release all of its data. Similarly, the Array of Things units are designed to dispatch information to Argonne National Laboratory for quality control and calibration, then on to the City of Chicago for mass dissemination through its open data portal.

In Glasgow, the City Data Hub makes all the information gathered easily accessible to local residents. The city is counting on them to make use of it, too, by working closely with urban informatics groups at local universities, encouraging businesses to use the data on pedestrian density to determine where to establish new shops, and calling for enterprising citizens to come up with new solutions on their own. “It’s an opportunity to stimulate innovation within the city,” says Birchenall. “You don’t have to rely on the government. If the data is open, anyone could try to solve the city’s problems through technology.”

The flood of information could also create new challenges, according to Pete Beckman, director of the Exascale Technology and Computing Institute at Argonne and a leader in the Array of Things project. “We’ll have so much data about our smart cities, but will we have the operating system?” asks Beckman.

Overall, the changes to these smart cities will be incremental, whether they are driven by researchers like Beckman and Catlett, urban planners, private innovators, or some combination. “You’re not going to wake up one day and live in the city of the future,” says Townsend. “Cities are systems of systems. It takes time to bring about large-scale change, but in the future I think we will be living in cities that fundamentally operate differently.”

Further Reading

Townsend, A.

Smart Cities: Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for a New Utopia, W.W. Norton, 2013.

Li, T., Keahey, K., Sankaran, R., Beckman, P., and Raicu, I.

A Cloud-based Interactive Data Infrastructure for Sensor Networks, IEEE/ACM Supercomputing/SC, 2014.

Shin, D.H.

Ubiquitous City: Urban Technologies, Urban Infrastructure, and Urban Informatics, The Journal of Information Science, 2009.

Carvalho, L.

Smart Cities from Scratch? A Socio-Technical Perspective, The Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 2014.

Future City Glasgow: A Day in the Life http://bit.ly/1GMuHwP

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment