The speed with which the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic undertook the economy of the U.S. left businesses, including universities, with very little time to adapt their standard practices to a virtual environment.

For computer science instructors, the sudden shift required hours of re-designing syllabi, technology, and expectations. Those adjustments may have been best expressed by a single sentence shared by two Cornell University instructors, professor emeritus David Gries and senior lecturer Michael Clarkson, in adapting their second-year course on object-oriented programming and data structures: "In redesigning the course, we have emphasized learning and compassion over grades and logistics," the two noted in observations shared with the university's computer science news organization.

"That was actually a phrase I kept repeating to many of my colleagues over the past couple months, too," Clarkson said. "My thinking on this was it's such an extraordinary time that it's okay if maybe some of the things we would usually do to give very careful grades or deadlines got lost a little bit, in terms of just providing students the opportunities to do the learning they needed to do and then to demonstrate that."

As students dispersed to homes around the world, Gries and Clarkson's adaptations were echoed by similar actions throughout the academic sphere. As spring turned to summer, instructors were still in a state of limbo, waiting for their universities to make clear how many students would be returning, how many would be allowed in classrooms, and how much of the virtual world of instruction would remain in place for an unknown period of time.

For instance, at Cornell, which hoped to issue formal guidelines on its plans for the fall 2020 semester by early July, Clarkson anticipated that classes would have to be limited to 30 or 40 people in a 200-seat lecture hall. Not only would such classes appear to be sparsely populated, he said, but trying to figure out which students in a given course would be attending live lectures and which would be following online on any given day is likely to be a logistical nightmare.

"By any technical definition of large you want to use, all of our courses are large," Clarkson said, "so given the constraints that will be necessary, as a department we basically won't be able to go back to in-person classes. It will have to be online.

"I really wish I could be back in the classroom with students. I normally teach large courses, with 400-600 students, and there is an energy in that kind of classroom that just does not exist online. I suspect that's true for even 20-person courses or five-person courses. You get that kind of energy when you are discussing things in a room with people, whether it's a small group or large group."

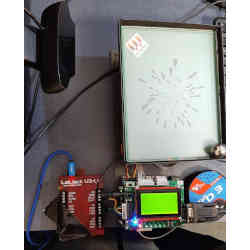

Boston University assistant professor of computer science Renato Mancuso expressed similar sentiments. Mancuso said he found himself scrambling to modify not only theoretical material, but also hardware that could be manipulated remotely for an upper-level embedded systems course.

Mancuso successfully created an interactive feedback system using data acquisition devices to replace joysticks in the lab.

"I showed them that the device could potentially be used to replace the joystick itself and make the system think there was a joystick attached, when it was just another digital device generating a joystick-like signal," Mancuso said. "I think that was a learning moment for them. It was for me; I never thought about using that particular DAQ (data acquisition device) this way, so I learned something myself."

Though he said he was happy he was able to provide students the hands-on experience the course promised remotely, he still missed the instant feedback of being in the same place at the same time with the students.

Mancuso said he likes to think of himself as an performer, for whom instant feedback helps to propel the material forward. "Sometimes I make mistakes on purpose because I know students like to correct the professor," he said. "I like to go in the middle of the class and interact. Sometimes I'll make a more complicated statement and stop and look around the class and look at their faces and see if they get it, or if they want me to expand on it."

In taking his classes online, Mancuso said he sometimes did not receive even audio feedback. "And I am always competing for their attention. They could be doing something else and probably are. It's human nature to get distracted by whatever feels more compelling in the instant, and they know the conference will be recorded, which is fine, I don't care about that. But I feel I am missing the interaction with my students that in the end keeps the lecture alive."

How To Test?

Both Mancuso and Clarkson said one of the biggest adjustments they had to make was in designing tests. In doing so, they needed to consider students would have access to reference materials and, being scattered around the world, could not be expected to take the test at the same time.

"In CS 2110, the way we 'solved' it was by eliminating exams," Clarkson said. "This was again going back to the notion of giving people a way to demonstrate that they had learned something, and be a little less concerned about what grades precisely meant this semester. So, we gave weekly quizzes. They were based on two lectures so they knew exactly what to study, which is different than a cumulative exam. We gave them a really detailed study guide. We created question banks from which random questions were drawn so students would get different copies of the quiz."

Mancuso said he found it liberating to shift tests from a 45- to 90-minute evaluation of how well students had memorized material to a 48-hour unsupervised exercise. "I could make the tests now in a way that the students were forced to think," he said. "And I told them you can Google this stuff, open the book, open the notes, look at the videos of the lectures – as long as you solve the exercise at hand, which was code that I wrote. They could not possibly find it online, so they were forced to reason on what's going on. Because of the specific type of course I teach, sometimes it's about the logic and sometimes about the timing of certain events, and how that code evolves depends on the sequence of events that happen on the system.

"That gave me a way to sweep the exam into being more favorable to those people who can critically think about the problem rather than just retrieve it from their memory. I saw this in the final grades. The ones who were clearly following and on track were also those who outshined the rest of their peers on the exam. Although the whole class did very well, I could tell the evaluation was fair in that sense.

"I have to tell you I am seriously rethinking the way I run my exams, especially for these advanced courses. When the students are 200 to 300 in a room, it's a little harder to coordinate an exam that is of this form. But for a smaller class, of 30-60 people, I think it's very beneficial to give an exam that gives them an opportunity to really think things through. I have to remain in compliance with BU's guidance going forward, of course. For the mid-term in the fall, I know I have the freedom to adopt this format and I will. For the final, I will have to stay with whatever BU prefers."

Stress Remains High Going Into Fall

Weekly quizzes were a draining experience for Clarkson. "Doing those quizzes the way we did was an exhausting amount of work, on top of everything else we were trying to do," he said. "We were having to create 30 to 40 questions a week. And in a normal semester when we give an exam, there is a certain stress level we expect. It's all sort of bouncing around. When we were giving weekly quizzes, even though they were worth just one-third of what an exam would have been, and even though bombing one wouldn't have that great an effect, every week the exam stress was there, and that is something I wouldn't wish on myself or my students.

"That's the hidden thing that not enough people are talking about. This was an exhausting semester for faculty. We took a three-week break here – students moved home and were bored, asking for assignments, and we were working overtime trying to figure out how to move things online. When we came back teaching was taking more time just because it takes more time to deliver content this way. And now the administration is saying over the summer we have to figure out how to teach online in the fall, except that we don't know how the fall is going to work yet. So I think faculty overwork and mental health needs to be a topic of conversation among administrators."

For undergraduates also, Mancuso said, the online experience takes away from the "college feeling" of communal living and learning. While upper-class courses during the pandemic might be giving students on the brink of entering the job market an idea of how much software development takes place online, there is no substitute for in-the-moment proximity.

"They could use collaborative tools, but at same time you can't replace the human component," Mancuso said. "After all, these are kids who come out of high school and they want that college feeling of going through this together, of being able to go over things and at the same time crack jokes; that college feeling can't be replaced when you go online."

Gregory Goth is an Oakville, CT-based writer who specializes in science and technology.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment