Since the fabled beginning of the modern running shoe—a Eureka! moment inspired by a university track coach’s waffle iron—billions of dollars have been made in the design and manufacture of shoes intended to cushion runners’ feet over the hundreds and even thousands of miles they put on them every year.

Despite the years of research and technological advancement in the field, however, the running shoe market still largely comes down to "rule of thumb" fitting. Shoes are made primarily in three patterns to combat excessive inward rolling of the foot, called pronation, on impact; runners of certain physiques are assumed to pronate more or less depending on their weight and gait, and are recommended shoe types based on that.

Rules of thumb do not work so well for feet, however, and finding a shoe that proves comfortable and protective can be a lengthy, expensive, and sometimes painful trial-and-error process.

By all indications, that is about to change, through a combination of computer vision-enabled scanning and three-dimensional (3D) printing (additive manufacturing) techniques that could provide each and every athlete custom shoes.

Crowded starting line

Three of the globe’s best-known makers of shoes and athletic apparel have announced or introduced 3D-printed shoes in the past year. In addition to the 3D printing process called selective laser sintering (SLS), which entails heating a plastic powder with a laser and layering the resulting material in selected areas, at least two of the three have announced an increased computational role in the design and manufacture of these shoes:

- Herzogenaurach, Germany-based Adidas in October 2015 announced its Futurecraft 3D shoe prototype, which promises a custom 3D printed midsole (the cushioned part of the shoe) based on individual measurements. "Creating a flexible, fully breathable carbon copy of the athlete’s own footprint, matching exact contours and pressure points, it will set the athlete up for the best running experience," Adidas said in a prepared statement. "Linked with existing data sourcing and footscan technologies, it opens unique opportunities for immediate in-store fittings."

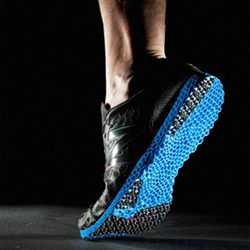

- Both Baltimore, MD-based Under Armour and Boston-based New Balance have gone beyond the prototype stage. Under Armour debuted its 3D-printed training shoe, the Architech, in March; the shoe features a lattice midsole designed by Autodesk’s Within generative design software. Under Armour produced just 96 pairs of the $300 shoes, which sold out. New Balance released 44 pairs of its 3D-printed midsole shoe, the $400 Zante Generate, on April 15.

The near-term market size for 3D-printed athletic shoes is still a matter for speculation; the Architech and Zante Generate cost twice as much as the most expensive mass-produced running shoes, and none of the companies provided any information beyond prepared press materials about their products, including how, when, or if they planned to begin "mass customization" of 3D-printed shoes for the mass market.

Slip-in sweet spot

A Vancouver, BC-based startup has demonstrated there is great pent-up demand for custom 3D-printed athletic footwear components at the right price point.

Wiivv Wearables, founded in July 2014, listed a modest $50,000 goal for its custom 3D-printed Base insole on the Kickstarter crowdfunding site in January 2016. The company had raised more than $250,000 by late April (in addition to $3.5 million in venture capital), and was already shipping the first 4,000 pairs of insoles, which sell for $75. Jen Riley, Wiivv’s director of marketing, said the insole’s appeal is based on a combination of economy (custom orthotics designed by podiatric professionals sell for between $300 and $600) and quality. While off-the-shelf insoles can cost as little as $10, they do not offer custom support.

The Wiivv insole also features in-the-home ordering convenience via a smartphone photo and measuring app, which uses a customization engine created in-house to convert 200 measuring points, including medial arch and foot size, from a two-dimensional file to a 3D file. Using the SLS method, the company creates a 3D nylon shell for each insole, to which is added a top sheet with neoprene cushioning, a padded silicon heel cup, and anti-slip tread. Riley said the insoles are made to work with factory-installed insoles in each pair of shoes, not replace them.

Wiivv executives consider the insole just the beginning of what they can do with 3D design. "We have had conversations with purveyors of custom everything," Riley said. "The technology we have built gives us the ability to make a custom nose piece for a goggle, earplugs, a custom piece of a bra, or a knee brace, to name a few."

Riley also did not dismiss the notion that a startup like Wiivv may someday be running on the heels of long-established brands in the field. The company’s technology and manufacturing technique allow it to do "anything," she said. "The choice we’re making is what is the best approach for us as a startup. We are definitely looking at footwear–and that’s where I will stop."

Wiivv is not alone in offering custom 3D printed insoles. Leuven, Belgium-based 3D printing vendor Materialise, which is partnering with Adidas on its Futurecraft shoe, has joined another Belgian company, RSscan International, a pioneer in foot scanning technology, to offer the 3D-printed Phits insole, through a joint venture called "RSPrint Powered by Materialise."

The insoles, for which individual dealers set retail pricing, are designed and printed based on professional measurements performed by the RSscan footscan scanning bed at one of 50 dealers worldwide (mainly orthotics and prosthetics practices, physiotherapists, podiatrists, and some specialized retail running stores worldwide, according to Phits marketing manager Tom Peeters). The footscan scanning technology underlying the Phits product was originally developed in 1994 at the request of Adidas.

Clearly, in 3D-printed athletic footwear, the game is afoot.

Gregory Goth is an Oakville, CT-based writer who specializes in science and technology.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment