Technology has brought us many wonderful things, but chatbots are not one of them. On banking and e-commerce sites, for instance, where these text-based conversational agents have been pressed into service to replace customer-support staff, even simple requests are often met with baffling arrays of options.

For example, a bank’s online chatbot recently asked me which of four types of savings account I was interested in – but it did not explain how they differed from each other. When I typed in “I don’t know” the bankbot replied tersely: “That is not an option”. It then looped me back to those original options. No wonder some consumer commentators – like this one at Forbes – say such clumsy chatbot implementations are “killing customer service”.

So, when I heard researchers in Canada had decided to add a sense of humor to chatbots, I feared the worst. Surely making light of giving people inadequate information would be adding insult to injury? Well, apparently not: the researchers have found that comedy-capable chatbots could have an important role, although in education – not customer support.

Speaking at the virtual Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI2021) in May, human-computer interaction researchers led by Jessy Ceha and Ken Jen Lee of the University of Waterloo in Ontario, Canada, described how their team set out to investigate whether a particular way of studying a subject, called learning-by-teaching, might be enhanced by a witty chatbot.

In garden variety learning-by-teaching, typically three students research a subject using certain teacher-approved resources like books, Websites, diagrams, and photographs. They then prepare a lesson and teach that subject to another small group of students, the process of lesson-planning having helped them not only improve their own factual recall of the subject at hand, but also, in having to work out how to teach the subject, develop their problem-solving skills.

The Waterloo team wondered, what if the teaching group got to coach a smart chatbot instead of fellow students? Further, they wondered whether a chatbot with a sense of humor, in getting a few laughs out of its teachers, might better motivate them, lower their stress and anxiety levels, and help them learn more?

“We wanted to explore the use of humor by virtual agents to see if it enhances learning experiences and outcomes,” said Ceha.

They then had to wonder, what type of humor should their chatbot exhibit? In an influential piece of research (cited no less than 800 times) published in 2003, psychologists at the University of Western Ontario, who study personality, identified four broad styles of humor:

- affiliative – simply telling jokes;

- self-deprecatory – making yourself the butt of your humor;

- self-enhancing – using humor for self-aggrandizement;

- aggressive – self-aggrandizing at the expense of others.

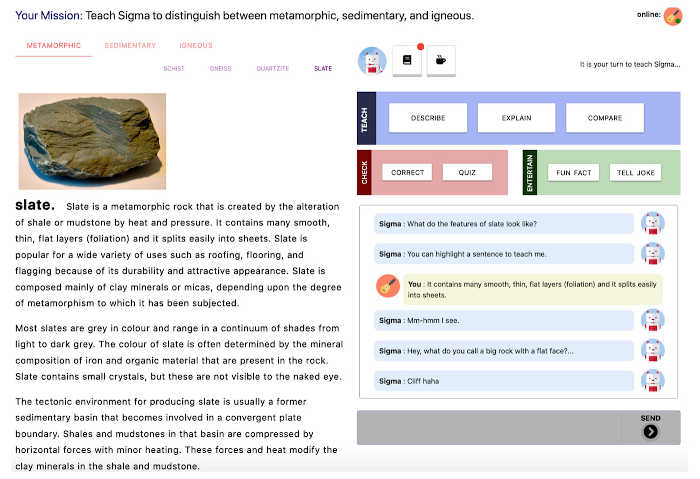

Only the first two varieties, those Western Ontario psychologists determined, are likely to be “conducive to social well-being and building relationships,” says Ceha. The researchers decided to program a teachable virtual agent called Sigma to exhibit either joke-telling or self-deprecating forms of humor as it was being taught. Sigma itself is hosted on an online learning-by-teaching computer platform called Curiosity Notebook, which permits experimentation with teachable agents of different architectures.

For their humor experiment, 58 people volunteered to teach Sigma some basic geology: how to classify sedimentary, igneous, and metamorphic rocks. Curiosity Notebook served up rock images and key geological facts associated with them on the left window of the screen, while the right window hosted Sigma’s text-based chat interface.

Credit: University of Waterloo

The entire human-chatbot interaction was driven by Sigma as it asked questions, made statements about what it had learned, and attempted to interject some humor (with jokes contributed by six creative writers hired from a crowdsourcing site).

In the affiliative, joke-telling mode, Sigma would be shown a photo of a metamorphic rock like slate, and it would ask the volunteer teacher to describe its properties. Sigma would then interrupt the description with a comment like: “Hey, what do you call a big rock with a flat face? Cliff. Ha ha.”

In self-deprecating mode, Sigma’s wit would run something like: “You know that feeling when you’re taught something and you understand it right away? Yeah, not me. Ha ha.”

As a control, the tests were also run in a neutral mode, sans wit.

The results were encouraging. “We found that participants who interacted with the agent with an affiliative humor style showed an increase in motivation during the teaching task, and an increase in the amount of effort they put into teaching the agent,” Ceha says.

While the volunteers teaching Sigma in its self-deprecating mode also showed an increase in effort, they didn’t enjoy it anywhere near as much, perhaps because the self-deprecating humor was a bit of a downer, diminishing the teacher’s self-confidence, the Waterloo team theorized.

The volunteers’ personal humor style was also a factor: people who like cracking gags put more effort into teaching Sigma in its joke-telling mode than in its self-deprecating style, for instance.

The team concluded that while humor can enhance educational chatbot interactions, care must be taken to supply agents that take into account the humor styles of users.

The Waterloo team now plans to investigate that most critical of comedic parameters, timing, by working to determine when is the best time to make a humorous interjection, and how often.

Elizabeth Churchill, director of User Experience at Google in Mountain View, CA, described the team’s results as “fascinating.” Churchill observed, “There is increasing interest in the creation of conversational agents and chatbots with personalities, and sense of humor is key to personality, and personality in turn leads to more human-agent engagement.”

An interesting finding of this work, Churchill says, “is that types of humor definitely matter. In social situations, we often use self-deprecation to defuse tension and appear humble, vulnerable, authentic, and reduce hierarchies. But self-deprecation by a teacher can backfire when there is a power dynamic, as in education, the teacher needs to maintain a sense of authority.

“Self-deprecation by a student, meanwhile, can lead educators with low self-efficacy to feel they are failing in their role. I think that is particularly relevant here because in this paradigm, the participant is both the student and the teacher; there is a whole lot going on there.”

Churchill says she would be interested to see the chat agent riff off the learner-teacher’s own sense of humor style. “I do wish they’d tested if the agent would respond to participants’ humor. Could this rapport be two-way? I am not sure how much work has been done on agents that can detect humor, but that would truly be a rapport-building win.”

Paul Marks is a technology journalist, writer, and editor based in London, U.K.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment