A remarkable thing about the human brain is its ability to distinguish between faces; a fleeting glance at a person is often enough to form a memory that lasts a lifetime. Yet when government, businesses, and others have attempted to use computers for facial recognition, according to the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC), facial recognition systems boast an accuracy rate of only about 61 percent.

Times, and technologies, change. Facial recognition and processing systems–first developed in the 1960s and commercially available for well over a decade–are now emerging as serious tools in fields as diverse as marketing, healthcare, and security. "Researchers are beginning to build systems that provide practical value," observes Matthew Turk, a professor in the computer science department at the University of California, Santa Barbara. "There is growing interest in deploying the technology."

The benefits of these systems are clear, even if the technology is still a bit fuzzy. Already, some researchers are using such systems to better communicate with autistic children; law enforcement agencies are deploying the technology to spot wanted or dangerous individuals, and some retailers in the U.K., including supermarket giant Tesco, are using the technology to profile shoppers by age and gender and serve up relevant ads in their stores.

A Better Image

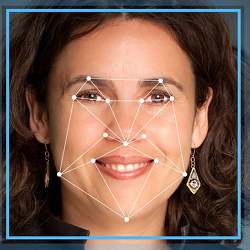

Facial analysis technology works in a fairly straightforward way. A computer plugs in the pixels captured by a camera or other sensing device and applies an algorithm to identify facial features and map their relationship to one other. By applying geometric or statistical formulas, the computer can match an image with other known images–and presumably validate the identity of the person.

Jeffrey Cohn, an adjunct professor of computer science at the Robotics Institute at Carnegie Mellon University and an expert in the use of computers to understand facial expressions, says improvements in processing power, better algorithms, 3-D modeling techniques, and improved training methods are catapulting both facial recognition and expression recognition technologies forward at a rapid pace. "We are beginning to see meaningful results," he says.

In the U.S., the National Security Agency is feeding millions of images a day into computers in order to identify terrorists and other threats. Worldwide, a growing number of security and passport control agencies are comparing photographs from visas with actual camera images to verify a person’s identity.

The technology also allows Mac computer users to group images of a person, and Android phones now support apps that use facial recognition to unlock those devices.

Facial expression analysis is a particularly promising area, Cohn says. He and other researchers are developing systems that can be used to identify facial expressions and social competence in autistic children, and depression and pain levels in both children and adults. "In pre-verbal or non-verbal children, or someone that is intubated and unable to express their pain level through words, it becomes possible to interpret when an analgesic is needed." He says the technology also could be used to detect drowsy or inattentive drivers–using indicators such as blink rates, eye closure, and head motion.

According to Turk, the technology also could be used to detect tiny strokes and other medical events.

Focus on Accuracy

Facial recognition and facial expression technologies still are not quite ready for prime time, however. For one thing, off-angle image capture–typically more than 20 degrees–generates problems, notes Ralph Gross, a post-doctorate fellow at Carnegie Mellon University. In addition, poor lighting, and objects such as sunglasses, scarfs, and masks, can defeat facial recognition systems. Changes in hair and aging can also affect results, as can a man who doesn’t shave for a few days or grows a beard. Even seemingly insignificant changes in a face–such as a smile or frown–can confuse many of today’s systems.

Also, current facial expression systems reveal an emotion, but not the underlying thinking, Cohn says. "A system may detect that a person is anxious, but the question becomes: is the individual anxious because he is afraid of being caught, or fearful about being accused of a crime he didn’t commit?" As researchers continue to feed data into systems—typically focusing on lots of different individuals—Cohn says these systems will continue to become smarter, and error rates will continue to decline (some systems now boast accuracy rates between 80% and 90%).

Turk believes the technology will move into the mainstream of society—and likely be deployed widely for security and other purposes—over the next decade. "What makes facial recognition and facial expression systems so appealing is that, in the end, you always have your face with you."

Samuel Greengard is an author and journalist based in West Linn, OR.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment