By now, the story is familiar: CD sales are falling. Digital music sales are growing, but have not offset the loss. The music business is struggling to adapt to a new technological era. It’s not the first time. At the turn of the 20th century, for instance, as the phonograph gained popularity, the industry’s model of compensation and copyright was suddenly thrown into question. Previously, composers of popular songs relied on the sale of sheet music for their income. After all, musicians needed sheet music to learn and perform a work, even if individual performances generated no royalties. Once performances could be recorded and sold or broadcast on the radio, however, the system grew less appealing to both groups of artists, who were essentially getting paid once for something that could be consumed thousands of discrete, different times. Eventually, collection societies were set up to make sure each party had a share in the new revenue streams.

Today, musical copyright is most prominently embodied not by sheet music but by audio recordings, along with their translations and derivatives (that is, their copies). Yet computers have made light work of reproducing most audio recordings, and the industry is unable to prevent what many young fans are now used to—free copies of their favorite songs from online file-sharing networks like BitTorrent and LimeWire. Legal barriers, like the injunctions imposed by the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) against copying protected works or circumventing their digital protections, are unpopular and difficult to enforce. (The industry’s John Doe suits have touched a mere fraction of file sharers, and their effect on the overall volume of illegal downloads is questionable.) Technological barriers, like the widespread security standards and controls known as digital rights management (DRM), have been even less effective.

DRM attempts to control the way digital media are used by preventing purchasers from copying or converting them to other formats. In theory, it gives content providers absolute power over how their work is consumed, enabling them to restrict even uses that are ordinarily covered by the fair use doctrine. Purchase a DVD in Europe, and you’ll be unable to play it on a DVD player in the U.S. because of region-coding DRM. What’s more, according to the DMCA, it would be illegal for you to copy your DVD’s contents into a different format, or otherwise attempt to circumvent its region-coding controls. To take a musical example, until recently songs purchased in Apple’s popular iTunes music store could only be played on an iPod due to the company’s proprietary DRM.

Entertainment businesses say they need DRM to prevent the theft of products that represent their livelihood. In practice, however, DRM has been a uniform failure when it comes to preventing piracy. Those who are engaged in large-scale, unauthorized commercial duplication find DRM “trivial to defeat,” says Jessica Litman, a professor of law at the University of Michigan. The people who don’t find it trivial: ordinary consumers, who are often frustrated to discover that their purchases are restricted in unintuitive and cumbersome ways.

In the music industry, at least, change is underway. In 2007, Amazon announced the creation of a digital music store that offered DRM-free songs, and in January 2009, Apple finalized a deal with music companies to remove anti-copying restrictions on the songs it sold through iTunes. Since iTunes is the world’s most popular digital music vendor—and the iPod its most popular player—critics complained the deal would only further solidify Apple’s hold on the industry. Yet because consumers can now switch to a different music player without losing the songs they’ve purchased, the prediction seems dubious.

“As long as the cost of switching technologies is low, I don’t think Apple will exert an undue influence on consumers,” says Edward Feiten, a professor of computer science and public affairs at Princeton University.

What about piracy? Since DRM never halted musical piracy in the first place, experts say, there’s little reason to believe its absence will have much effect. In fact, piracy may well decrease thanks to a tiered pricing scheme in the Apple deal whereby older and less popular songs are less expensive than the latest hits. “The easier it is to buy legitimate high-quality, high-value products,” explains Felten, “the less of a market there is for pirated versions.” By way of illustration, he points to the 2008 release of Spore, a hotly anticipated game whose restrictive DRM system not only prevented purchasers from installing it on more than three computers, but surreptitiously installed a separate program called SecuROM on their hard drives. Angry gamers responded by posting copies of the game online, making Spore the most pirated game on the Internet.

DRM is being “wielded as a powerful tool” against unapproved technologies, says Aaron Perzanowski.

DRM and Movies

Yet DRM is nowhere near dead outside the music business. Hollywood, protected thus far from piracy by the large file size of the average feature film, continues to employ it as movies become available through illegal file-sharing networks. Buy a movie on iTunes, and you’ll still face daunting restrictions about the number and kind of devices you can play it on. Buy a DVD, and you’ll be unable to make a personal-use copy to watch on your laptop or in the car.

DRM has also proven useful as a legal weapon. Kaleidescape, a company whose digital “jukeboxes” organize and store personal media collections, was sued in 2004 by the DVD Content Control Association, which licenses the Content Scrambling System that protects most DVDs. (In 2007, a judge ruled there was no breach of the license; the case is still open on appeal.)

The Kaleidescape case is instructive, experts say, since it shows that preventing piracy isn’t necessarily Hollywood’s biggest concern. Entry-level Kaleidescape systems start at $10,000—unlikely purchases for would-be copyright infringers. “Instead, DRM is wielded as a powerful tool to prevent the development and emergence of unapproved technologies. In some instances, that may overlap with some concern over infringement, but as the Kaleidescape example shows, it need not,” says Aaron Perzanowski, a research fellow at the Berkeley Center for Law & Technology.

Indeed, the real question typically comes down to one of business models: Can companies preserve their current revenue structures through DRM or in court, or must they find some other way of making money? For music, the iTunes model appears to be a viable one, though questions still remain. For movies, the path is less clear. What will happen when DVDs become obsolete? Will consumers take out subscriptions to online movie services, or make discrete one-time purchases? “Nobody knows what the marketplace of the future will look like,” says Litman. And the wholesale copyright reform that digital activists long for is years away.

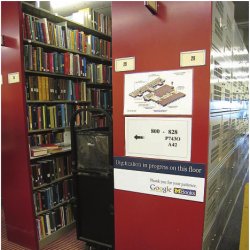

One industry whose business model may soon be radically transformed is publishing. Under the terms of a recent settlement reached with the Authors Guild (which sued Google in 2005 to prevent the digitization and online excerpting of copyrighted books as part of its Book Search project), Google agreed to set up a book rights registry to collect and distribute payments to authors and publishers. Much like the collection societies that were established for musicians, the registry would pay copyright holders whenever Internet users elected to view or purchase a digital book; 63% of the fee would go to authors and publishers, and 37% to Google.

If approved, the settlement would be “striking in its scope and potential future impact,” says Deirdre Mulligan, a professor of law at the University of California, Berkeley’s School of Information. It is nonetheless highly controversial. Some, like James Grimmelmann, a New York Law School professor, believe it is a “universal win compared with the status quo.” Others are disappointed by what they see as a missed opportunity to set a powerful court precedent for fair use in the digital age, and the undeniable danger of monopoly. “No other competitors appear poised to undertake similar efforts and risk copyright legislation,” says Perzanowski.

One thing, at least, is clear: It frees the courts to consider other industries’ complaints as they slouch toward the digital age.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment