What is the greatest secret to connecting with the public and funders about computer science, even if its applications are clearly intended to transform and improve our lives?

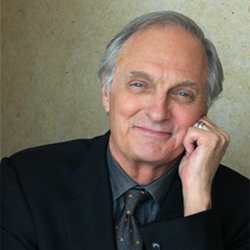

In his keynote speech at the SC15 (supercomputing) conference in Austin, TX, Tuesday, Nov. 17, Alan Alda said, first, establish familiarity with your audience, then tell them a story, making it an adventure, turning on some "dramatic action."

Alda, best known for his acting roles and, more recently, for helping to establish the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook University, told an auditorium of high-performance computer and networking scientists his own story about falling ill on an 8,000-foot mountain in Chile in 2014. He said he felt intense pain and thought it was his appendix; death seemed near. The local medic agreed, though Alda was sure he had never done anything medically before in his life. He did realize Alda needed to get off the mountain and to a hospital. An ambulance was found, Alda said, but it appeared to be a prop out of his 1970s TV show M*A*S*H about the Korean War in the early 1950s. The ambulance managed to take him down a bumpy road for an hour and a half to a town where a doctor listened to him describe his symptoms, then looked him in the eye and said the problem was his intestines, not his appendix, explaining, "…some of your intestine has gone bad, and we need to remove it and connect the two good parts…," a procedure called end-to-end anastomosis. Alda recalled he had done many such procedures himself on M*A*S*H (which stands for "mobile army surgical hospital"). The doctor had apparently seen him do them on the show years before as a teenager–and so had all the fictional background he needed to proceed.

Alda recalled a scientist he interviewed for a Scientific American Frontiers TV show who explained her science clearly but only when looking directly at Alda, using vocabulary he (a non-scientist) could understand. Unfortunately, she preferred to turn her attention to the camera, falling into a canned lecture she had given many times before. Alda had to stop her and remind her to connect with and communicate directly with him, that her ideas would then connect with the TV audience.

The problem, Alda said, is it is not easy to communicate, so you, a computer scientist, should imagine you are on a blind date with your audience, wondering "How far can I go?," perhaps pursuing the three stages of love: attraction, infatuation, and commitment. Here, commitment means you want people to understand.

To illustrate how a good story is indeed an adventure in which the hero has to overcome an obstacle to achieve greatness, Alda enlisted a member of the SC15 audience to stand beside him on stage, where two tables stood about 15 feet apart. On one was a pitcher of water and a clear glass goblet. Alda filled the goblet to the brim, then asked the volunteer to deliver the goblet and its entire content of water to the other table. "Don’t spill a drop," he said, "or your entire village will die."

The volunteer indeed completed her mission without spilling a drop and won the applause and appreciation of Alda and everyone else in the hall. Alda reminded us all there was, in fact, no village, and the dramatic action was all in our imaginations. It was also a good way to help the assembled computer scientists remember the lesson about communicating their highly technical science, as well as their own thinking.

Tuning in to the other person is, Alda said, the responsibility of the person doing the talking.

Andrew Rosenbloom is senior editor of Communications.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment