A generation ago, political science curricula were largely dominated by the study of rhetoric and philosophical differences that precipitated policy and social changes. Students of political science learned the power of persuasion, not of calculation.

"Thirty years ago, they called it a social science, but it was almost in the humanities, because it was very rhetorical," said Kevin Knudson, a professor of mathematics at the University of Florida.

In the intervening years, Knudson observed that more and more data science is becoming commonplace in the study of the social sciences and the implementation of policies that originate in that area of scholarship, while certain areas of public policy have remained stubbornly amorphous, more black art than black and white. One of the most vexing issues in this category in democratic societies has been the ongoing debate over how to assure each voter's ballot carries equal weight, or as close to equal weight as theoretically possible. This ideal is often subverted by gerrymandering, an electoral districting plan intentionally drawn to give unfair advantage to a political party in the majority at the time of the plan's creation.

In societies such as the U.K., where parliamentary constituency boundaries are the responsibility of independent commissions, overtly partisan gerrymandering is minimized. However, in the U.S., where most electoral districts are drawn by state legislatures, the debate over gerrymandering has become increasingly rancorous.

What makes it difficult to discern whether or not a particular plan is gerrymandered unfairly is the elastic nature of population patterns and the variables affecting them, such as geographic barriers, or attributes of a region that draw "communities of interest," those who prefer to live near others with similar outlooks and philosophies.

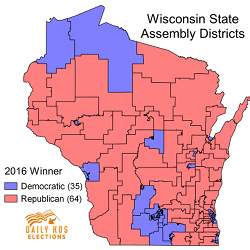

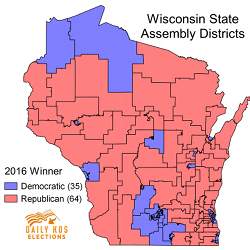

A case likely to be on the U.S. Supreme Court's docket in the next term, however, may become a landmark in quantifying fairness around legislative district creation. The case, Gill v. Whitford, concerns legislative redistricting in Wisconsin. A U.S. federal district court found the Wisconsin state house plan adopted by the state's Republican-controlled legislature in 2011 was an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander.

According to the non-partisan Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law, the case could be exemplified by some stark results: Democrats won a majority of the statewide Assembly vote in 2012 and 2014, yet Republicans won 60 of the 99 Assembly seats. Republicans argued that partisan skews in the map reflect not nefarious intent, but rather a natural geographic advantage they have in redistricting as a result of Democrats clustering in cities while Republicans are spread out more evenly throughout the state. The court, however, said the state's natural political geography "does not explain adequately the sizable disparate effect" seen in the 2012 and 2014 results.

At the heart of Gill v. Whitford, and other cases facing the Supreme Court and other federal jurisdictions, is the dilemma of defining exactly what constitutes overtly unfair partisan gerrymandering, and what falls within the bounds of allowable advantage reaped by voters' sentiment at the ballot. Simply stated, no clarifying standard has emerged—but that might be changing rapidly, as mathematicians and political scientists publish more work on computational platforms' ability to more fairly analyze and draw electoral maps that present a quantified idea of districts that may meet that as-yet-undefined standard.

Justices speak "computationally"

Wendy Tam Cho, a professor of political science, statistics, and Asian American studies at the University of Illinois, said one of the elements that may help judges finally set some sort of standard is that computational tools may finally have the necessary power and sophistication to model a sufficient number of alternatives. Cho, co-author of a paper that won the Common Cause 2016 Gerrymander Standard Writing Competition, said quantifying a fair districting process is a massive computational task. In their project as expressed in the paper, Cho and co-author Yan Y. Liu used the Blue Waters supercomputer at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications at the university.

"It's an idea I actually had 30 years ago," she said. "I actually wrote a little program 30 years ago and I ran it. It ran for two weeks and I was not getting anything close to what I needed to see."

Cho has also listened to the Supreme Court justices speak on electoral policy for 20 years, she said. In the 2004 Vieth v. Jubelirer case, which might be considered a precursor for Gill, Justice Antonin Scalia dismissed the possibility of ever setting a standard against which gerrymandering could be considered unfairly partisan. However, Justice Anthony Kennedy, who in recent years has often been the swing vote between the conservative and liberal wings of the court, wrote that just because no standard had presented itself up to the time of the Vieth case did not mean one might not emerge, and Kennedy's words now seem prophetic.

"I've followed the Supreme Court on this the last two decades," Cho said. "I listen to them talk, and what they are saying I see with not just a law and political science lens, but with a math and computational lens. And to me it's very clear they are implicitly thinking in a computational manner. I don't think they realize that, but to me that's very clear. I don't think they realize how much computation is involved to get to the type of measure they are talking about in a legal sense. It's only recently, with the advent of supercomputers, that I decided to give it another shot, to devise a tool that will actually provide the type of measure, a legally viable measure, the Supreme Court will accept."

How many maps will it take?

Cho is not alone is tackling gerrymandering algorithmically. In 2014, Duke University professor Jonathan Mattingly and student Christy Vaughn developed a Monte Carlo simulation to try to calculate how fair results of the 2012 congressional election in North Carolina were in comparison to how the state's 13 congressional districts were drawn. Mattingly and Vaughn emphasized attributes allowable in drawing districts (equal partition of the population and the compactness of districts) in their experiment.

"When random districts are drawn and the results of the 2012 election were re-tabulated under the drawn districtings, we find that an average of 7.6 Democratic representatives are elected," the two wrote. "Ninety-five percent of the randomly sampled redistrictings produced between six and nine Democrats. Both of these facts are in stark contrast with the four Democrats elected in the 2012 elections with the same vote counts. This brings into serious question the idea that such elections represent the 'will of the people.' It underlines the ability of redistricting to undermine the democratic process, while on the face allowing democracy to proceed."

Mattingly and Vaughn reported on the results of 100 random runs of their model, and also calculated how many plans might be possible: 132500 ≈ 7.2×102784. So, while 100 runs might serve as a proof of concept, it is likely many, many more must be done to establish legal viability, and that is where massively capable computing platforms shine. The appeal, Cho said, is that the persons responsible for programming the model can assure the computer's parameters are as impartial as possible, and that impartiality can be based on innumerable variables.

"One of the things you can do with a computer, unlike a human, is tell it, 'Here are the criteria you can use,'" Cho said. "You can even tell it, for instance, 'This is how your decision process will work. You may use partisanship, but that is not your driving motivation. You must also consider if you are adding a given block to the district, am I keeping the city together, am I preserving communities of interest, am I keeping it compact?' You are basically turning the computer into a map drawer, but you are able to control its preferences.

"What we're trying to understand with the computer drawing over and over again is what level of partisan outcome, leaning one way or the other, is not really partisan," she said, "because a lot of these maps are constrained by wanting to keep cities together or how people live in a region or where the mountains are. You have to draw a lot of maps to understand what a map that uses partisanship, but doesn't use it excessively, looks like. If you only do a few, it's like tossing a coin once. The number of ways you can actually draw maps is astronomical. A million is actually a drop in the bucket."

Critical momentum

Recent decisions in federal courts have encouraged opponents of lopsided districting plans that the time is ripe to establish more quantifiable districts. In the latest decision, the Supreme Court itself affirmed that two congressional districts in North Carolina were the result of gerrymanders that illegally conflated race and party affiliation—one of the affected districts, the 12th, which winds its way in a narrow ribbon along the Interstate 85 highway, is often considered one of the nation's most gerrymandered.

Several of the research community's leading experts on the new quantification approach to electoral districting will be participating in an August "Geometry of Redistricting" workshop at Tufts University. Response to the workshop was so strong, the organizers have added regional workshops in Wisconsin, North Carolina (where Mattingly, who expanded his original paper into a gerrymandering quantification project at Duke, is listed as the lead organizer), Texas, and California.

One sign of the growing academic community around unfair districting is the divergent conclusions some of the pioneers are reaching on early contenders for the standard of fairness, such as the "efficiency gap," one of the factors expected to figure prominently in the Whitford case. Cho, for instance, in her most recent paper, says the efficiency gap is inadequate in defining unfair partisanship.

Attorney Jeffrey Wice, who has been advising on redistricting matters since the 1980s (and who will be presenting at the Tufts workshop), said some of the research that emphasizes finding some sort of consensus on what constitutes district compactness might also fall short.

"I prefer using ranked prioritized criteria when I approach a redistricting situation," Wice said. "I look to equal population, the Voting Rights Act, jurisdictional boundaries, communities of interest, compactness, and contiguity as all being important, but compactness is often one of the secondary measures. For example, we also work with municipal lines that historically have been in place and not every city, village, or town is round or square. You may find many bizarre shapes, but those shapes usually take precedence when you are drawing a district to keep towns and cities intact, with one representative."

Knudson said the recent surge in research is a good start, but that getting the work out of the research lab and into public policy will take time and effort.

"A lot of these ideas are pretty arcane," he said. "With that court case, we may begin to see some clarity start to emerge, but we still will have to litigate this everywhere, because legislatures in individual states will not say, 'Yeah, we've been unfair.' So it will have to be some sort of grassroots effort."

Gregory Goth is an Oakville, CT-based writer who specializes in science and technology.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment