Criminals do not respect boundaries. In fact, they benefit when there is weak coordination among fragmented, independent jurisdictions. The failure to share information or resources among these isolated domains increases criminals’ opportunities to remain undetected over time.

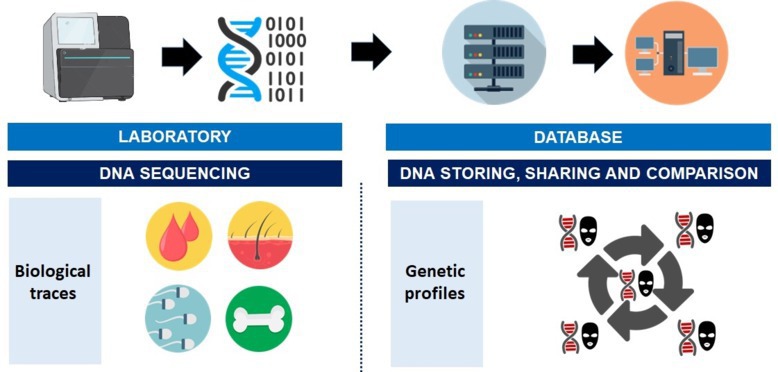

GENis is a software product developed in Argentina for the storage, sharing, and comparison of digital genetic profiles used in judicial investigations (see the accompanying figure).a

What makes GENis unique is its combination of distinctive features, including an open source, multi-tier design; a focus on international cooperation; and a capability to assist in missing persons cases.

Currently in use by judicial institutions in several Latin American countries, GENis is the only forensic DNA database software that is publicly available for immediate use with no requirements. CODIS, originally developed by the FBI for the U.S., has been adopted by more than 50 countries but requires a specific memorandum of understanding (MOU) agreement and is not open source. Commercial software products, such as FSS-iD, eQMS, RapidDNA, Small Pond, and Bode Match, cover a partial set of functionalities that GENis brings together.b

GENis was created as part of an open, collaborative project for the development of a digital tool to improve the administration of justice worldwide. The software was conceived as a digital public good—thereby fulfilling United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 16—and was the result of synergy among academia, industry, and government. Strong ties were built with local actors, fostering the democratization of knowledge in DNA and bioinformatics.

To date, GENis has been widely adopted by the Argentine judiciary, including the National Supreme Court of Justice, the National DNA Data Bank, and more than 20 provincial judicial systems.

At the international level, GENis has been adopted by the attorney general’s office of Mexico City and by the only forensic laboratory in the Dominican Republic. Conversations with public institutions from other Latin American countries are also being held.

Development. The development of GENis began in 2014, conducted by a multidisciplinary team of more than 100 experts. It was based on four pillars, all of which are core orientations set by the International Society of Forensic Genetics:

Adoption of international standards on forensic genetics

Reliance on agile development methodologies

The use of open source technologies

An emphasis on information security.

Due to the software’s need to handle sensitive personal information, security concerns have been at the core of GENis. The use of resources such as double-factor user identification, role-based access control, traceability and auditing functionality, and cryptography reflect the software’s “security by design” development framework.

Limitations and risks. DNA technology for identification, conviction, or exoneration is so powerful that many believe it to be infallible. However, DNA evidence has several important limitations:

It might be undetectable, overlooked, or insufficient.

Its analysis is subject to error and bias.

DNA profiles can be misinterpreted, and their importance exaggerated.

Even if DNA is detected at a crime scene, it is inconclusive in determining guilt.

Therefore, DNA needs to be analyzed within a framework of other evidence, rather than used as a standalone answer to solving crimes. For example, the mere presence of DNA does not necessarily tell investigators when or how biological material was left at a crime scene. What matters is the context.c

Ethical issues. Given that DNA contains unique personal information, genetic data can affect fundamental rights and present moral dilemmas, which require democratic control mechanisms and special oversight. It is true, however, that in forensic genetics this warning is partially bounded from the start, as forensic genetic profiles are extracted from non-coding DNA sequences. This means the data does not contain individual genetic references that could pose a potential risk to a person’s employability or insurability. Nonetheless, GENis developers took additional safeguards by formally consulting the National Bioethics Committee to limit the kinds of data and analysis available in the software by design.

Conclusion. GENis was conceived as a digital public good to exploit the combined benefits of genetic science and information technology to synergistically improve the effectiveness of global criminal courts.

Following international standards, it was necessary to make the software’s underlying calculation models transparent to support the independent reproducibility of its results. This was a central attribute designed to guard against possible challenges to experts’ findings.

A growing global community is working together to promote awareness of the promises and perils of DNA. For instance, DNA Compass is a recent open platform that enables the navigation of personal genomic information without command-line knowledge. This effort aims at increasing genetic literacy and empowering everyone to understand their personal genomic data.d

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Manuel Crespillo Márquez (Spain), Víctor Pozos Cuellar (Mexico), Eileen Riego Trejo (Dominican Republic), Mauricio Chacon Hernández (Costa Rica), Pablo Santibañez Purizaga (Perú), Ariel Chernomoretz, Javier Iserte and Franco Marsico (Argentina), Raymond McCauley (U.S.), and Nathalie Alvarado, Mauricio García Mejía, and Fernando Cafferata (IADB) for their valuable contributions to this project.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment