Robots of all kinds are in widespread use today. They are often humanoid machines. However, the definition of a robot is unclear, as is the distinction from automata. Already Heron of Alexandria (1st century) created such devices. Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) also designed a wealth of drawings of sophisticated objects, see Leonardo da Vinci’s Robot Lion and Leonardo’s Self-driving Car. There were also fake automatons, e.g. the chess-playing Turk by Wolfgang von Kempelen (1770).

In the 18th century, automaton figures experienced their heyday. Some of these creations are still fully functional and are regularly demonstrated. This development began primarily with Jacques Vaucanson. His three machines, duck, flute player, and drummer (1738), are unfortunately not preserved. In 1745, he had also manufactured an automatic tape controlled loom. Numerous automated figures were damaged or destroyed in fires, including the draughtsman-writer of Henri Maillardet (Franklin Institute, Philadelphia).

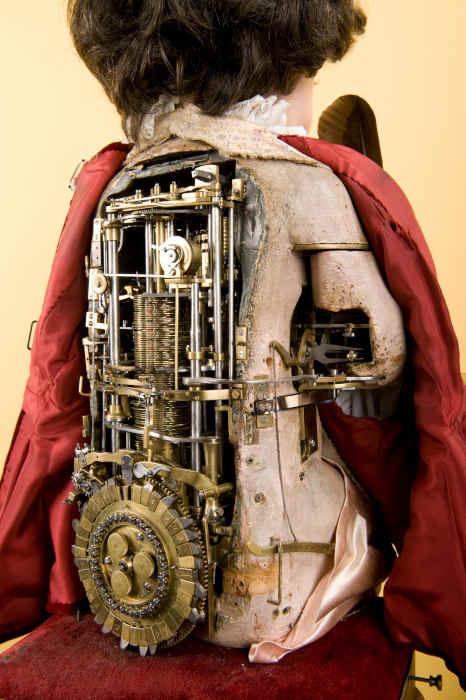

The three musical, drawing, and writing automata (see Figs. 1 and 2) in the Musée d’art et d’histoire, Neuchâtel (Switzerland, MahN) from 1774 are considered to be the most beautiful automaton figures in the world. Makers of these masterpieces are Pierre Jaquet-Droz, Henri-Louis Jaquet-Droz, and Jean-Frederic Leschot.

Fig. 1: Automaton figures of Jaquet-Droz (1774). The three grandiose Neuchâtel androids are regarded as the world’s most magnificent and technically most sophisticated automaton figures. In spite of their high age, they are still completely functional. The tripartite group is made up of a draughtsman (at left), a musician (center), and a writer (right). Credit: Musée d’art et d’histoire, Neuchâtel.

Fig. 2: The writer. The entire highly complex control mechanism of the programmable handwriting automaton is located in the body of the child. The (horizontal) cams in the middle column ensure the flawless form of the letters. The text content is defined with the (vertical) cam wheel and stored to the cams. Credit: Musée d’art et d’histoire, Neuchâtel.

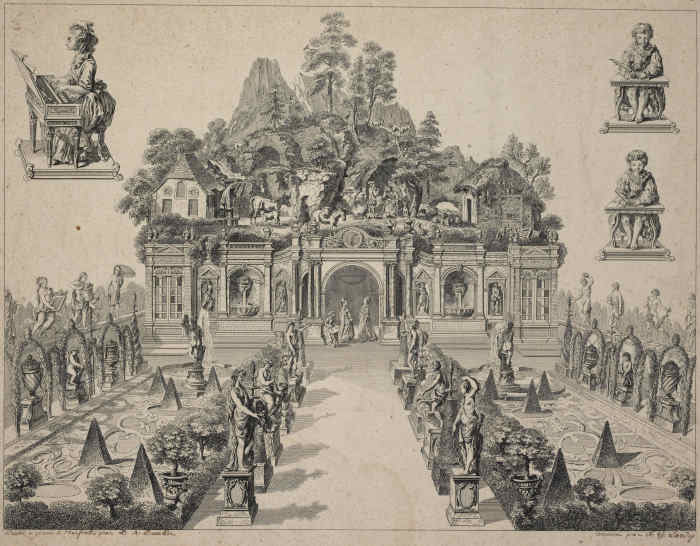

Henri-Louis Jaquet-Droz came to London at the end of 1775, followed by his father Pierre Jaquet-Droz in 1776. They displayed four automatons in King Street, Covent Garden. The incredibly multifaceted craggy landscape automaton with the name “Grotto” (see Fig. 3) has been lost. This accommodated a hut, a mill, an aviary (bird house), sheep, goats, and music makers. The automaton theater also featured a brook, waterfalls, and fountains.

Fig. 3: Grotto. Only the above illustration of this Jaquet-Droz automaton has survived. At the upper left, one can see the musician, and at the upper right, the writer, and (underneath) the draughtsman. Etching and engraving of Balthasar Anton Dunker, completed by François Guillaume Lardy (1775), Credit: Trustees of the British Museum, London.

Uncertain is the origin of another android, see Who Manufacturered the Mysterious Chinese Android?

Another superb musical automaton, the dulcimer player (1784), is the work of the Germans Peter Kintzing and David Roentgen (see Fig. 4). It is located in the Musée des arts et métiers in Paris.

Fig. 4: The dulcimer player (1784). The captivating dulcimer player of Peter Kintzing utilizes tiny hammers for the dulcimer. The head and eyes move, but not the upper body. The control mechanism is not in the automaton figure but underneath this. In contrast to the musician of Henri-Louis Jaquet-Droz, sophisticated finger mechanics is missing. Credit: Musée des arts et métiers/Cnam, Paris, picture: Pascal Faligot.

The golden witch is also great (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 5: The “old humpbacked witch” automaton. This android (from the beginning of the nineteenth century) depicts an old woman who moves with the help of two wooden walking sticks. Credit: Musée d’horlogerie du Locle, Château des Monts, Le Locle NE, picture: Renaud Sterchi.

Sources

You will find detailed descriptions of these and many other historical automatons and robots in:

Bruderer, Herbert: Meilensteine der Rechentechnik, De Gruyter Oldenbourg, Berlin/Boston, 3. Auflage 2020, Band 1, 970 Seiten, 577 Abbildungen, 114 Tabellen, https://www.degruyter.com/view/title/567028?rskey=xoRERF&result=7

Bruderer, Herbert: Meilensteine der Rechentechnik, De Gruyter Oldenbourg, Berlin/Boston, 3. Auflage 2020, Band 2, 1055 Seiten, 138 Abbildungen, 37 Tabellen, https://www.degruyter.com/view/title/567221?rskey=A8Y4Gb&result=4

Bruderer, Herbert: Milestones in Analog and Digital Computing, Springer Nature Switzerland AG, Cham, 3rd edition 2020, 2 volumes, 2113 pages, 715 illustrations, 151 tables, https://www.springer.com/de/book/9783030409739

Acknowledgements

Part of this translation was done by Dr. John McMinn, who translated my book “Meilensteine der Rechentechnik” into English.

Herbert Bruderer is a retired lecturer in didactics of computer science at ETH Zurich. More recently, he has been an historian of technology. bruderer@retired.ethz.ch, herbert.bruderer@bluewin.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment