ACM represents the global community of computing professionals, researchers, and educators. As such, the organization must be responsive to the needs of the field in an international context. Among ACM members, 48% are from the U.S., with only 3% from Canada and 4% from Latin America and the Caribbean. The percentages for Africa and the Middle East are combined with Europe at 18%, and 27% of the membership comes from Asia and the Pacific Rim. These statistics suggest that our membership is not proportionally representative of the global population.1 Looking more closely, only 20% of computer scientists in the U.S. are women,4 with racial minorities and people with disabilities also underrepresented.13 For instance, 70% of those earning science and engineering doctorates are white. People with disabilities are 9% of the U.S. population but only 3% of the STEM workforce,13 suggesting that disabled people are also underrepresented in computing. With so many underrepresented groups, and with computing jobs in the U.S. predicted to grow by 17% in the next decade, this presents a problem. An article in Forbes stated that “if the industry continues to source new hires through traditional pipelines without prioritizing workplace diversity, these jobs will be largely unavailable to an emerging workforce that is made up of women and underrepresented minorities.”12 Increasing diversity in computing is thus not only a liberal or moral matter; it is also necessary to keep pace with business needs, both in the U.S. and around the world.

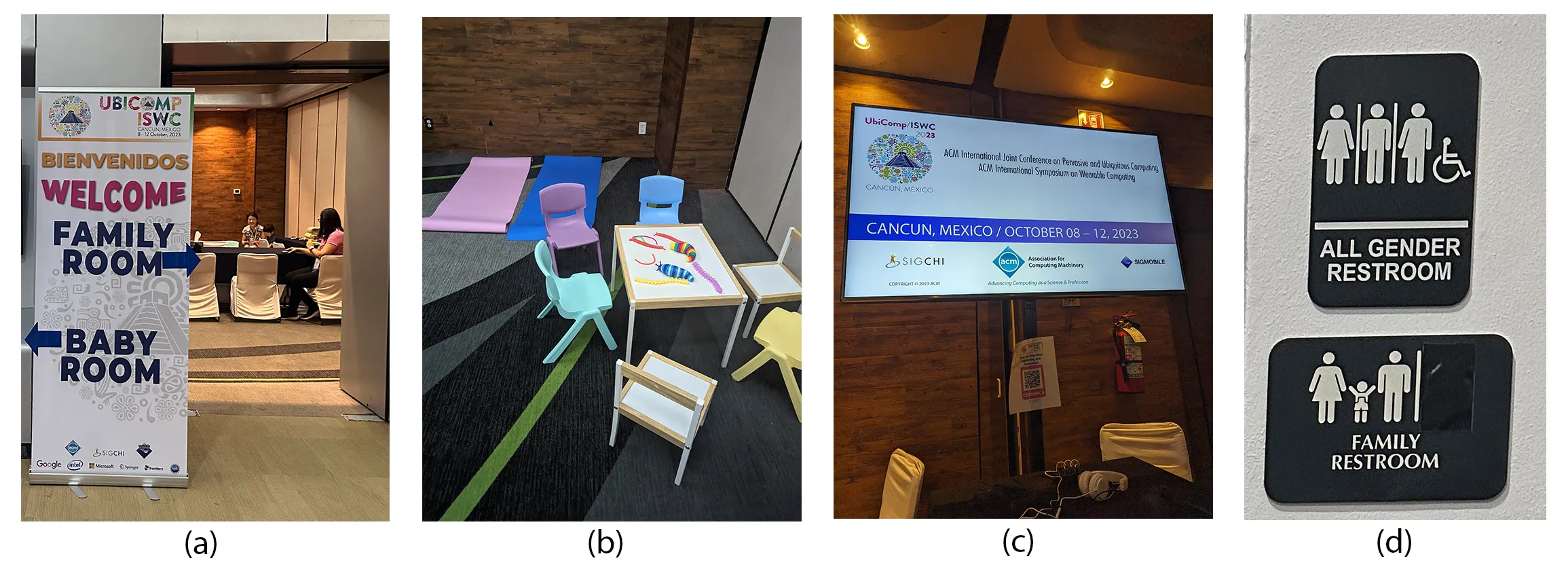

International conferences are an important vehicle through which we can increase diversity in computing. To that end, when running the 2023 UbiComp/ISWC conference,a we scheduled programs specifically aimed at improving diversity. This article lays out our efforts, their costs, and their effectiveness so others can learn from our successes and mistakes.

Key Insights

ACM membership is not representative of the global population in terms of gender, country of origin, race, or disability, yet achieving this diversity at conferences is critical to meeting the forecasted growth in computing jobs.

We recommend appointing an accessibility chair before site selection to aid in decision making.

Here, we outline best practices for achieving justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion (JEDI), showcasing both our initiatives and established best practices regarding accessibility.

Many JEDI initiatives can be financially viable but require both budgeting and the active involvement of conference planners who are sensitive to JEDI issues and local arrangement chairs.

The Conference

UbiComp/ISWC (ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing and International Symposium on Wearable Computers) is the premier ACM interdisciplinary venue where leading international researchers, designers, developers, and practitioners in the field present and discuss novel research in all areas of ubiquitous, pervasive, and wearable computing. In 2023, after a three-year hiatus during the COVID-19 pandemic, the conference returned to a fully in-person, single-location conference in Cancun, Mexico, drawing 548 attendees from 48 countries. As this was the first time that the conference was held in Mexico or Latin America, the conference organization team, which was approximately 25% Mexican, was excited for the challenge. To ensure access to the conference by a diverse audience, we aimed to make justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion (JEDI) core elements of the event.

Starting in 2019, we took steps to ensure that UbiComp/ISWC would be an inclusive conference, and though the conference was postponed until 2023 due to COVID-19, the plan from the beginning had been to make it our most inclusive conference to date. We undertook a number of initiatives to ensure that our values around JEDI were embedded in the conference and were serving all of our attendees. This included inviting (for the first time) an accessibility expert to join the site selection to ensure that all facilities were accessible and could support our equity needs.

Mexico has a rich cultural heritage; this, however, added to the challenges of our JEDI mission. Though our Mexican UbiComp/ISWC colleagues share the progressive values of our community, the practices of the convention center, hotels, restaurants, and other vendors were often distinct from those of the U.S., Europe, and Asia, where UbiComp/ISWC has typically been held. Mexico is 80% Catholic.5 Labor force participation for women is at 45.8%, compared with 77.5% for men.15 Same-sex marriage and homosexuality are both legal, but LGBTQIA+ people are still sometimes subject to employment discrimination, banned from the military, and often face housing discrimination.6 Disability is still stigmatized—only 15% of the disabled population receive secondary education, and only 47% of the disabled population are employed.11 It was therefore evident that we were facing relevant cultural differences that would affect our mission to support gender equity, LGBTQIA+ and disability, mental health, and neurodivergence, challenging our JEDI goals. In the next sections, we outline our initiatives, the challenges we faced, and the lessons we learned in the hope of modeling inclusive best practices for our community and others within the ACM family and beyond.

Engaging Local Community

A key goal in hosting UbiComp/ISWC in Mexico was to engage the local community, in doing so aiming to expand computing in Latin America beyond its current 4% of jobs. We implemented this goal at several levels, including the organizing committee, the local organizers, and the participants. Our organizing committee was co-chaired by key community leader and Mexican colleague Monica Tentori from the Ensenada Center for Scientific Research and Higher Education (CICESE) in Mexico. A third of our organizing committee spoke Spanish in addition to English, and came from a range of Latin American countries. Our professional conference organizer (PCO), Intermeeting (International Meeting Services S.A de C.V.), was staffed entirely by Mexican professionals. We also engaged volunteers from local universities in Cancun, including the Universidad Anáhuac Cancún, allowing them access to the conference at no cost. In addition, we featured a special program called the Americas Student Symposium on Emerging Technologies (ASSET) as part of SIGMOBILE’s student outreach program. All students in ASSET (mostly from Mexico) were new to UbiComp/ISWC and were provided with a mentor.

To engage authentically and meaningfully with the Indigenous population, we invited local artisans to install booths with native crafts in the conference center, allowing money to go back to the local community and not just to large international hotels. An Indigenous Mayan dance company performed at the reception, exposing our attendees to the Mayan tradition. Given that most of our attendees hailed from countries that historically led colonialist efforts against Indigenous populations, we provided reference material explaining the religious and cultural significance.b

Financial impact and trade-offs. The financial impact of working with a local PCO and engaging students from local universities was minimal. Our local PCO did not charge overhead for services and charged an advance fee of only US$4,500. A non-local PCO would typically be 10-to-20% of the overall budget, in our case about US$40,000 to US$80,000—significantly larger than the small fee charged by the local PCO. A non-local PCO would also not be equipped to honor local traditions, so it made more sense to choose a local PCO. Local student researchers and volunteers received complimentary registration. These students made up about 5% of the attendees (about 15 registrations). At US$140 to US$280 per registration for low- and middle-income students, the financial expense (about US$3,150) was less than 1% of registration revenue. But by engaging with these students, we gained access to resources from local universities (for example, our design exhibition needed mannequins, stands, and iPads that were borrowed from a local university) that saved the money that would have been used to buy and ship these items. We refer to costs less than US$2,000 (0.5% of the registration revenue) as negligible. Thus, both initiatives had a negligible or positive financial impact while providing invaluable opportunities to local workers and students and building the computing community in Latin America.

Broadening Participation

As indicated by the statistics cited earlier, people from North America constitute the majority of ACM members. Thus, one of the goals of UbiComp/ISWC 2023 was to increase participation from attendees from underrepresented countries and parts of the world, who typically would not be able to join this international event. We implemented five key efforts. First, following some other community examples, notably the CHI conference,c we introduced tiered registration fees, enabling students and ACM members from low-income countries to pay lower fees. Using income tiers defined by the World Bank,d attendees from low-income countries paid 75% of the high-income rate, and middle-income attendees paid 50%.e This resulted in 16% of our participants coming from middle-income countries and 9% coming from low-income countries that had never before been represented at the conference. Financially, reduced registration charges resulted in a budget reduction of US$47,250, which accounted for a little over 10% of our budget. To recoup some of these expenses, we applied for and received US$10,000 from the SIGCHI Development Fund (SDF),f which supports underrepresented groups and events for connecting communities. Second, we hosted two specialized and invited symposia, UbiComp4All and ASSET, to increase diversity in our community throughout South and Central America, allowing 30 students and early-career researchers to participate. Third, thanks to our SIGCHI and SIGMOBILE sponsors, we were able to award 15 attendees partial to full travel grants and provide free registrations to eight students who took part in the ASSET program. Fourth, in collaboration with N2Women,g we hosted a mentoring luncheon for 52 attendees (including 10 senior members). Finally, we hosted a diversity lunch with speakers covering topics such as autism, race, gender, immunocompromised status, first-generation college attendees, disability, and LGBT issues. Combining these efforts ensured this would be our most demographically diverse UbiComp/ISWC to date.

Supporting Families and Children

Women are underrepresented in computing.4 An issue that disproportionately affects women is childcare,8 which is critical for the full participation of women and parents in the scholarly community. We therefore pursued initiatives that addressed families and the needs of children. We worked with hotels and the conference center to offer childcare, and welcomed children to join the conference and any of the complementary social events together with their caregivers.

Our pre-arrival survey showed that nine participants took their families, including spouses and children, to UbiComp/ISWC. This resulted in a total of 11 children, ranging in age from 10 months to 10 years, who were planning to attend the conference and be present in some way at the conference site. Some attendees brought their spouses to care for the children, while others hired a professional caregiver. In addition to offering complimentary admission to all children, the conference also provided companion passes for any spouse, babysitters, or nannies accompanying the families, which gave them access to all common areas.

To allow attendees with families and children who joined them in Cancun to be able to take care of their children and effectively participate in the conference, we established a special area called the family room, welcoming families, children, caregivers, friends, and colleagues to use it throughout the conference (Figure 1). We also provided a direct liaison with trusted local childcare companies that could be hired to help take care of the children, either in the family room at the conference center or at the attendees’ hotels.

The family room was designed with a range of amenities, including a private space for breastfeeding or pumping and an open space used as a play area. The former included comfortable sofas, blankets, a microwave, and a fridge in which to store baby food. The latter included toys, blankets, coloring books, and a working space (tables and chairs) for parents. To allow for looking after the kids and attending sessions, we provided attendees with the ability to follow any of the three concurrent tracks and keynotes through live streaming the conference rooms in the family room. Caregivers and family members could watch the presentations on large screens and listen to the presenters using the provided headsets. Live captioning technology was also helpful for parents who could not wear headsets or who were D/deaf or hard of hearing (HoH).

We also created a dedicated family restroom (also used as an all-gender restroom) that was beside the family room and provided a changing mat, wipes, baby bottle brush, sponges, and dishwashing soap.

Finally, to ensure that children were safe, we designed and put in place numerous security and safety protocols. On the day prior to the pre-conference, we trained our student volunteers (SVs) and shared all protocols with them, including those for medical emergencies and missing children. Fortunately, none had to be used during the event.

Financial impact and trade-offs. The financial cost of the family room consisted of the items placed in the room, which was negligible (US$1,600); the cost of renting chairs, sofas, and so on, which was not negligible (US$3,900) but would have been necessary for any use of the room; and the cost of the audio and visual tech to live stream the presentations to the room (US$2,800). The key trade-off of reserving the family room was having to use a space that could have otherwise been used for one of the concurrent workshops or events. In our case, the conference center had enough space both for all accepted workshops and for the family room, but other venues might be more restricted.

Supporting Disability, Neurodivergence, and Accessibility

Also underrepresented in computing are people with disabilities.13 As an inclusive conference, it was key to support any attendees with disabilities and improve overall accessibility. In 2023 we had attendees with a range of disabilities and neurodivergences, including vision and hearing impairment, mobility limitations, autism, mental health conditions, and immunocompromised status, as well as allergies, celiac disease, and diabetes. As an aid for all attendees who were planning to attend the conference, we created an extensive accessibility FAQ,h in keeping with AccessSIGCHI guidelines.i We also made some unique access adaptions to accommodate the beach venue slated for the conference dinner, including laying decking on the beach to ensure wheelchair and cane users could access the reception.

Accessible website. Our legacy Web template was not accessible, so we engaged a Web accessibility consultant and revised the UbiComp/ISWC website to be WGAC 2.1 AA-level compliant.17 We selected AA compliance, based on the standing advice of AccessSIGCHI,j to target AA compliance. Our new accessible WordPress template was also adopted by the UbiComp/ISWC 2024 organizing committee.

Captioning. To support both people who were D/deaf or hard of hearing and those who had a first language other than English—and in line with our broadening participation initiatives that brought a number of students and young researchers from Latin America who spoke mostly Spanish—we provided captioning for all plenary sessions as well as the three parallel tracks presentations. Given the high cost of on-site, manual, real-time translation, we selected a professional company, Interprefy,k that was able to guarantee high-quality AI-generated captioning. Interprefy also offered real-time translation and text-to-speech in languages other than English that we thought would be useful for our audience. We placed large displays in the front of each conference room to make it easier to see the slides and included real-time captions. Captioning was also available via an app on mobile devices that provided real-time AI translation for free in Spanish, Mandarin, Japanese, and Korean. We selected the languages spoken by the highest number of attendees, with the exception of German, as most of our German colleagues were proficient in English. Captioning both supported the goal of increasing accessibility for people with disabilities and helped broaden international participation.

Supporting COVID safety. While the global COVID-19 pandemic was reclassified to an epidemic during our conference, and no requirement for testing and/or masking was prescribed by the conference organizers, we wanted to support attendees’ choice and sense of personal responsibility. We also had attendees who were immunocompromised due to both disability and pregnancy and thus were at significant risk of developing serious symptoms if they caught COVID. We did not feel comfortable requiring masking or testing, but we provided free masks to all participants to support those who were vulnerable. In an effort to enable easy access to testing, we sold COVID tests at the registration desk and provided stickers with the UbiComp/ISWC logo that said: “I tested negative for COVID.” We ensured that the conference chairs, accessibility chairs, and family chairs were all tested and had a sticker clearly displayed to promote awareness. While our budget did not allow us to test all attendees, we created a policy of testing any of our SVs who showed symptoms. We also asked all SVs to put a mask on when interacting with someone who was wearing a mask or visibly pregnant. When attendees expressed concerns about unmasked people coughing, we took the additional step of having our accessibility chair take those people aside discretely and offer them the option of masks and testing. Some of our participants brought their own air-quality monitors; we responded to their notifications if the air quality dropped below certain thresholds, asking that doors be opened and fans be placed to encourage air circulation. Overall, we believe these policies were successful in maintaining a delicate balance of supporting COVID-vulnerable people while respecting budgeting constraints and the individual rights of attendees not to mask.

Sensory rooms. We also wanted to support attendees’ mental health and offer mitigation opportunities for neurodivergent attendees with different tolerances for stimuli. We had a number of participants with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and other neurodivergent attendees who identified needs for high- and low-stimulation spaces. Based on prior experience, and in light of our focus on supporting diversity and inclusion, we also identified a number of other needs that we thought could be addressed in conjunction with neurodivergence. In particular, we identified the needs of attendees who wanted to follow their religious practices and have a place to pray, the need for people with disabilities or jet lag to rest, and the need of D/deaf and hard of hearing people to have a place quiet enough to communicate effectively.

To cater to all these needs, we decided to designate special sensory rooms that were accessible to all attendees. We divided the sensory rooms into three spaces (see Table): the silent room (Figure 2), the quiet room (Figure 3), and the chill room (Figure 4). We used the British Standards Institute’s “PAS 6463:2022 Design for the mind – Neurodiversity and the built environment – Guide” as our guidance for the space.2

| Room | Suggested Activities | Please Avoid |

|---|---|---|

| Silent |

|

|

| Quiet |

|

|

| Chill |

|

|

We received heartfelt thanks in person from neurodiverse attendees who used the sensory rooms repeatedly throughout the conference. The following message, sent spontaneously by a neurodivergent attendee as an email to the organizers and not as part of the formal survey, highlights the sensory rooms’ perceived value:

Both as a volunteer and as an attendee, I wanted to thank you for the inclusion of the sensory rooms, especially the Silent Room. This was my first academic conference and I was easily overwhelmed, so the rooms were a great place for me to calm down and recharge so that I would not have a meltdown…I wanted to send this email to illustrate how the inclusion of accessibility in conferences is a huge help to disabled students, and how much I appreciated the thoughts put into this conference.

Though these rooms were well used, we had to put up additional signage to discourage people from using the sensory rooms for video calls and meetings, especially the chill room. Overall, we strongly believe that sensory rooms should be part of any conference, since they are vital to a successful experience for neurodiverse attendees. We strongly recommend the inclusion of at least a high- and a low-stimulation space, the latter of which can also work as a prayer room.

Financial impact and trade-offs. The financial costs of these initiatives were minimal. The Web accessibility consultant charged a one-time fee of US$8,675 for a multi-year reusable template. This fee was supported by sponsorship of both SIGCHI and SIGMOBILE. The Interprefy captioning, translation, and technical support service cost US$7,280. Another service quoted captioning and equipment by itself at US$2,445 and translation at US$6,642 for 40 hours of a software translation service. (The service we chose did not provide the breakdown between translation and captioning.) The cost of supporting COVID safety (masks and tests were bought locally) was negligible. Maintaining the sensory rooms had a similar financial and logistical impact as the family room. The cost of renting equipment was necessary and the item costs were negligible, but the key trade-off was that one less room was available to potentially scale up workshops (which, however, did not affect our conference due to the numerous spaces available at our venues). We also were able to leverage a mechanism from the SIGCHI Development Fund to improve the accessibility of events to recoup some of these expenses.

Justice, Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (JEDI)

To be true to our dedication to JEDI, we wanted to also ensure that anybody who was going to attend our conference would feel included and that their values, including those involving racial diversity, sexual orientation, religious beliefs, and cultural practices, would be respected and, when appropriate, highlighted.

Pronouns. We asked all attendees if they wanted to specify their pronouns as part of registration. Choices included she/her, he/him, they/them, another combination not listed, or a choice not to specify. Anyone who specified pronouns had them listed on their badge. This section of the badge was left blank if someone chose not to specify.

JEDI ambassadors. In addition to the regular SVs, we recruited 11 “JEDI ambassadors,” students with expertise or lived experience with diversity issues, including those involving disability, neurodivergence, race, or language. The JEDI ambassadors staffed a dedicated booth, ensuring there was always one available. Multiple SVs noted they were glad to have the JEDI ambassadors around during their shift, which eased their work and empowered them to better assist and address all attendees’ needs.

Religious and cultural spaces. To accommodate religious needs, our participants were encouraged to use the silent room for silent prayer and the quiet room for meditation and yoga. Despite clear labeling, at least one religious attendee mentioned being unaware there was a prayer room, so in the future careful advertising is required.

Supporting dietary needs. As a global conference, we had participants with a wide range of dietary needs, including vegetarian, vegan, pescatarian, halal, kosher, celiac disease, lactose intolerance, diabetes, and allergies (nuts, shellfish, mango, onion, and cilantro). Some of these dietary needs, such those for diabetes and celiac disease, constitute legal disabilities as well. Many were novel to vendors in Mexico generally, and in particular to the vendors booked by the conference. To mitigate any allergy concerns, in the convention center we elected not to serve nuts, shellfish, mango, onion, and cilantro, as they could have led to anaphylaxis or other severe reactions. We also had paramedics on site to ensure any emergencies were handled. Our contracts with both the convention center and the hotels explicitly stated to avoid any pork in food served during the conference (for religious and allergy reasons) and that no shellfish or nuts were to be served either. At the convention center, we ensured all allergy food was prepared in a separate kitchen. Our contracts also required food with the 14 major allergens7 to be labeled. While our vendors agreed to do this, they kept labeling food with ingredients but not allergens. For instance, our vendors would say “beef sandwich with mustard,” but would not label the item as having gluten or sulfates. It took us until the last day of the conference to get the vendors on board. We had one celiac and two people with lactose intolerance who required minor medical intervention. Thankfully, the paramedics were there to provide treatment.

Overall, there was good awareness of how strictly kosher food needed to be prepared (under Rabbinical guidance), but less awareness that food for strict Muslims might also require supervision. Our Jewish attendees ultimately only required pork- and shellfish-free food, and our Muslim attendees were comfortable with pork and alcohol-free food, provided that all meat was halal. Halal meat prepared under strict religious guidance is considerably more expensive. As the budget did not allow halal meat to be served at all meals, we provided vegetarian options suitable for observant Muslims (and Jews) instead. We offered halal-certified meat meals in the main conference reception to promote inclusivity; our Muslim colleagues found this to be a lovely compromise, as indicated by a tweet from a delighted attendee. On one occasion, a Muslim colleague was visibly distraught after biting into a meat pie that he was told was vegetarian. Reminding him of the no-pork policy for the conference eased his mind considerably. For future conferences, we recommend labeling all food with allergen pictures to avoid translation issues.

Many of these issues arose in part because of language barriers, but also because, like the U.S., Mexico does not require food manufacturers to label traces of allergens from shared machinery. Though a food item’s ingredients list might say it contains only raisins, one does not know if it was cross-contaminated with nuts or gluten, perhaps because the machine was previously used to make trail mix. We witnessed very low awareness from staff that only food straight from nature (fruit, vegetables, unprocessed meat, and uncut cheese) was free from cross-contamination, and that processed foods (sauces or corn tortillas) were only gluten-, nut-, or lactose-free if explicitly labeled. This made it very challenging to provide safe food, requiring hours of meetings with organizers and caterers, and still resulted in minor illnesses.

To resolve more difficult dietary needs, we ended up going to the grocery store to purchase snacks and lunch food, as lactose-free and celiac-safe food were especially problematic. Although external food technically was not allowed in the conference venue, the only way to actually support some of these dietary needs was to purchase food offsite and announce its availability to all SVs and JEDI ambassadors, as well as over email to people who registered with allergies. It was not an ideal solution, but it allowed us to achieve our social justice goals.

Financial impact and trade-offs. The financial impact of these initiatives varied. The JEDI ambassadors were provided free registration in exchange for their service (at the expense of US$6,000). This expense was accounted for by reserving a portion of the free SV registrations, which are built into the budget, for the JEDI ambassadors. The main trade-off was that there were fewer SVs to perform other tasks. However, in practice, the JEDI ambassadors helped with these tasks when they were available, so the impact was minimal. Reserving religious and cultural spaces had the same trade-off as the family room and the sensory rooms, in that it was mainly logistical. There was a larger financial impact in supporting the various dietary needs. Additional charges were added to support halal and kosher diets (for example, at one dinner event, it cost an extra US$110 per person to support attendees who needed halal and kosher diets, 11 people in total). Further charges were added to support allergies and serious intolerances (for example, lactose intolerance). We were charged about 25% extra for lunch meals that supported these needs.

Conference Survey

In addition to informal feedback emailed to chairs and the posts on X/Twitter mentioned earlier, we conducted a formal post-conference survey to understand how we met our diversity goals. Of our 548 attendees, 82 participants completed the survey, though many people elected to skip the diversity questions. This means that while some responses to the diversity section are out of 70 respondents, others were answered by as few as 15 attendees. Given the lack of statistical significance, we report raw data only. The majority of participants who completed the survey (62 out of 70—note that 12 people skipped even this question) reported liking the conference, with eight individuals listing their reaction as neutral, and no one saying they did not like the conference. With regard to specific diversity issues, 23 out of 33 respondents reported using the family or sensory rooms. When asked to rate the family room’s importance, 11 out of 19 listed them as very important, 6 out of 19 listed them as important, two out of 19 were neutral, and zero out of 19 indicated they were unimportant or not at all important. When asked about the sensory rooms, 11 out of 22 listed them as very important, six out of 22 listed them as important, two out of 22 were neutral, and three out of 22 indicated they were not too important or not at all important. Additionally, two attendees highlighted these considerations as the most enjoyable aspect of their entire conference experience. Real-time captioning was used by 14 out of 20 respondents, though real-time translation was used by only two out of 15 respondents. Nonetheless, the participants who used the captioning largely perceived it as valuable: 11 out of 21 listed it as very important and five out of 21 listed it as important, with only five out of 21 listing it as neutral or unimportant. When asked about their favorite and least favorite aspects of the conference, people included diversity accommodations such as the family room and halal food as among the best aspects. Addressing food-allergy needs was listed as needing improvement. In short, the conference survey reported no major unmet diversity needs, and suggested that while not everyone needed family rooms, sensory rooms, captioning, and translation, those who did greatly appreciated them.

Lessons Learned

We believe that our initiative toward improving justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion enriched and elevated the experiences of our attendees to a new level, and we aspire for our community to use this standard going forward. Putting these initiatives in place, however, has not been easy. We learned a lot, and we can do better by fixing some of the problems we have been able to surface. Despite our desire to have an inclusive conference, not everything went perfectly, and given the international venue there were some cultural points of friction, discussed in the following sections.

Availability of changing stations. Though we requested that changing stations be installed in the public men’s bathrooms in the convention center, this request was met with confusion. We explained how single fathers might bring children to the conference, and how we had couples where both parents were participating as professional attendees and shared childcare duties equally. Though we were unable to get changing tables installed in the men’s bathrooms, our solution was to place a temporary changing table in the dedicated family bathroom. This was a reasonable compromise to overcome cultural friction.

Recommendation: We recommend conference organizers try to understand local cultures and conventions around gender roles, and have frank discussions around how to accommodate the pervasive values of gender equity in child caring in our community.

Accessible and all-gender bathrooms. Ensuring equitable bathroom facilities for people of all genders and disabilities was important to us. At the initial site visit, we observed how the conference center had bathrooms only for binary-gendered people, and that the bathrooms were not up to international standards for disabled access, as they lacked transfer space, movable grab bars, in-case-of-emergency pull cords, as well as automatic faucets, soap dispensers, and door openers. We identified a space in the convention center for an all-gender bathroom, but this bathroom was not accessible. At the contract negotiation stage, we asked for a bathroom to be remodeled to be accessible, but were unable to negotiate a financial penalty if the specified work was not completed on time. Ultimately, male and female bathrooms were remodeled to have increased transfer space and a movable grab bar, but emergency pull cords and automatic faucets, soap dispensers, and door openers were not provided. If one of our attendees was a wheelchair user who required transfer space as well as an all-gender bathroom, this would have been inadequate. Thankfully, our arrangement met the needs of our disabled and non-binary attendees.

Recommendation: It is important to consider the intersectional needs of participants. Given how there is considerable variety by country, we recommend that conference organizers specify accessible, all-gender bathrooms (see UN guidelines16) at the contract stage, including a financial penalty if these are not provided.

Demographic data on race and ethnicity. When looking for ethnically diverse speakers for the diversity luncheon, we realized that during registration, there was no demographic data collected on race, which made it challenging to understand how to best support attendees with different needs.

Recommendation: We recommend that conferences ask attendees to share their race and ethnicity (if they are comfortable doing so) to better implement JEDI initiatives and track their progress to improve the participation of racial and ethnic minorities in the field.

Better dietary options for registration. Catering and conference staff dedicated to serving food indicated some dietary information, such as “no pork/shellfish,” “halal,” or “no mango,” but these indications were not enough for some of our attendees to be comfortable with respect to their degree of religious observance or seriousness of allergy.

Recommendation: Provide tick-box options during registration for dietary options. Provide a secondary option to indicate whether the food should be kosher or halal, or if it needs to be prepared under strict religious guidance. For allergies, allow participants to indicate severity so organizers can anticipate possible risks.

Supporting serious allergies and intolerances. When there are language barriers or poor food-labeling laws, it is extremely difficult to ensure that all allergies and intolerances are addressed.

Recommendation: Ban food that can cause anaphylaxis like nuts and shellfish, and provide allergy stickers on all badges that clearly indicate dietary needs to overcome language differences. Also introduce a new chair position dedicated to food—a “diet chair” who speaks the primary language of the local venue would be ideal. Additionally, encourage frank conversation about the likelihood of obtaining truly celiac-safe, nut-free, or lactose-free food. Provide shelf-stable and microwavable meals that are allergen-free if local conditions do not allow. It is vital to provide safe food for everyone, regardless of disability. Research shows that excluding people in social situations based on dietary needs has adverse mental health implications3; in the interest of equity, this must be avoided.

Social events and sensory overload. We created three dedicated sensory rooms at the conference and a quiet room at the SV party, and were requested to create a low-stimulation space at the receptions. Despite our efforts to mitigate high stimuli, one attendee with ASD became overstimulated and had a meltdown, resulting in tears. Although we specified to avoid strobe lights for all conference events, an unexpected strobe light showed up at the SV party. Quick interventions and good communication between attendees with ASD and the accessibility chair allowed us to stop this before it became a problem.

Recommendation: We recommend always having a trained accessibility chair who checks in with neurodivergent attendees to make sure they are fully supported during all conference events. At minimum, one low-sensory space should be provided at all social events. All AV contracts should explicitly avoid strobe lights to support attendees with ASD and epilepsy.

Nursing space at social events. Though we created a dedicated nursing space at the convention center, a nursing mother pointed out there was no nursing facility available at the conference reception and other social events outside the conference center.

Recommendation: Have a designated space for nursing at social events.

T-shirts. We purchased conference t-shirts in pink and blue to match our logo. This was an oversight, and while some volunteers did not care, others thought that the colors mapped to binary gender. In addition, t-shirts were tailored incorrectly for plus-size women.

Recommendation: Be mindful of color connotations and have t-shirts in men’s and women’s sizes to accommodate a variety of body shapes. Let attendees select their t-shirt size with clear waist and chest measurements, given that sizes vary across countries.

Lack of accessibility of student volunteer system. Our legacy system for SVs to book their volunteer hours was not WGAC 2.1 AA compliant, making it difficult for low-vision individuals to participate. We introduced a workaround using a Google Doc to ensure accessibility when required.

Recommendation: In addition to auditing outward-facing tools for accessibility, ensure that the conference reviewing and scheduling systems are also compliant.

Avoiding ableist language and ensuring accessible content. Attendees noted that sometimes the language used by organizers, presenters, and volunteers contained terms that many in the disabled community consider offensive, such as discussing people “suffering” from disability. The Transactions on Accessible Computing (TACCESS) journal and the ASSETS guidelines9 recommend that researchers “avoid terms that reflect a bias or projected feelings of an individual’s situation.” Similarly, they recommend one not use terms like normal or healthy but instead use terms like nondisabled or persons without disabilities (or without sight or hearing). In the conference Q&A sessions, we noticed some pushback on using microphones for questions, even though they are a known best practice for including D/deaf and hard of hearing colleagues. We also noticed that some presentations were not designed to be accessible.

Recommendation: Adopt the TACCESS guidelines for “Writing about Accessibility”9 and provide guidance to authors on creating accessible presentations.l

Accessibility needs are different for every conference. We recognize that the needs of our attendees may differ from those of attendees at other venues. For instance, we did not have any D/deaf attendees who communicated via sign language, which would have required a large budget to cover sign language interpreters. In the U.S., such services run US$20 to $55 an hour.14 As sign language is not universal and comes in language-specific formats (even U.S. and U.K. sign languages are different), this can necessitate flying in an interpreter with an international attendee. For instance, the ACM CHI 2023 conference budgeted to cover sign language interpreters for three different sign languages. Though some countries may provide disabled employees with interpreters to travel with them, this varies substantially by country. Thus, for attendees from countries without this type of disability support, if the conference does not provide sign language interpreters, it represents a significant extra cost for the attendees, disadvantaging disabled researchers. This same argument holds for live captioners, which are needed because AI captioning is still not 100% reliable and not available for out-of-session academic discussions during breaks and networking events.

Recommendation: All conferences’ budgets should include the cost for sign language interpreters and live captioners, to the extent possible. When this is not possible, we recommend looking for alternate funds to cover these costs. For instance, the SIGCHI Gary Marsden Travel Awardsm can be used to cover disability-related travel costs for SIGCHI conferences. We recommend that conference organizers investigate sources of extra funds to cover such contingencies in advance. We also recommend that ACM create centralized resources to allow conferences to better support disabled attendees with these needs.

Conclusion

Achieving real justice, equality, diversity, and inclusion at an international conference with hundreds of attendees with disparate backgrounds and needs is an incredibly ambitious goal but, as highlighted in the introduction, supporting diversity in computing conferences is vital to ensuring adequate numbers of diverse computing professionals. Doing so requires attention to scores of decisions, from t-shirts to food, from bathrooms to family rooms, all of which are imbued with implicit biases and cultural assumptions. In a large international conference setting, it is imperative to explore and consider language and cultural differences so we can find culturally sensitive solutions to equity issues. We believe the initiatives we created for UbiComp/ISWC 2023 illustrate that we can do a lot, and that we should keep doing it, even if perfect JEDI support might not be achievable. Here, we provided examples of best practices, as well as pitfalls to be avoided. We also shared financial data and post-test survey data that show that these efforts are both financially manageable and vital for minoritized participants. We hope this article inspires our colleagues across ACM to implement similar (and better) diversity initiatives across all our future conferences.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Emani Dotch for photography and Yifan Feng for his assistance in preparing this document. We would also like to thank our hardworking UbiComp/ISWC 2023 JEDI ambassadors, including Faustino Zarif Carlos León Altamirano, Isabel Lopez Hurtado, Paith Philemon, Jessica Beltrán Márquez, Qijia Shao, Mara Ulloa, Gwangbin Kim, Robert Pettys-Baker, Steven Rick, and Pallabi Bhowmick. Thanks also to the whole UbiComp/ISWC 2023 organizing committee for the JEDI mission, including the JEDI co-chair Temiloluwa Prioleau. We also thank the attendees who were patient in getting their JEDI needs met.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment