The uncontrolled dissemination of misinformation, such as the Cambridge Analytica scandal; attempts of foreign interference; and the significant polarization in the 2016 U.S. Presidential election raised serious concerns that those issues could happen again in other countries and upcoming elections. Those concerns were mainly associated with the indiscriminate use of targeted advertising,1,17 abuse of social bots,4 and the increasingly individualized feed algorithms from social media platforms.9 However, in the 2018 presidential election in Brazil, misinformation campaigns operated within a new yet poorly understood digital space: messaging platforms such as WhatsApp and Telegram.

With hundreds of millions of monthly active users, WhatsApp and Telegram, among other messaging apps, have become key pillars of digital communication today, allowing synchronized and affordable interactions for its users. In Brazil, everyone with a cellphone uses WhatsApp or Telegram, which weaves these platforms into the fabric of everyday life. Individuals of all ages use these platforms not only to communicate but also for various other purposes, including educational, commercial, and professional activities. Users can create groups for any reason—students can organize a party or connect with others to discuss homework or school issues, parents can connect to share information, and local communities can connect to discuss recent events. The ease of sharing multimedia messages with texts, audio, video, and images with groups of friends, family, and co-workers has made these applications a cheaper and more accessible alternative to SMS and other means of communication.

Compared to other, less popular message platforms in Brazil, such as Discord and Signal, WhatsApp has a key advantage that favors its large penetration in the Brazilian market: the zero-rating policy.10 The use of WhatsApp is not accounted for in most mobile plans, making them appear as “free” to users. With a high number of digitally illiterate people and low-income population, apps offered through a zero-rating policy tend to be perceived as “the Internet” to a large population in Brazil. This practice induces users to spend more time in WhatsApp, skewing online content consumption to what is most shared in WhatsApp. Additionally, zero-rating limits users’ engagement with a more complex online experience. For example, users who receive misinformation through WhatsApp may have difficulties in verifying that information in other sources on the Web. Thus, from the point of view of a misinformation campaign, WhatsApp represents a popular and daily used platform where users may have difficulties checking the veracity of a story in other Internet sources.

To show concrete examples, we present two manipulated—images properly debunked by fact-checking agencies—which were widely disseminated though WhatsApp during presidential campaigns in Brazil.16 In Figure 1, the former Brazilian president Dilma Rousseff is falsely portrayed alongside Fidel Castro, the former president of Cuba, as an attempt to associate Rousseff with communism, promoting the fear of a communist dictatorship in Brazil. The original photo was taken when Rousseff was only 11 years old, unequivocally establishing the falseness of the image. Figure 2 shows a manipulated image that portrays the Brazilian president Lula close to the man who stabbed Jair Bolsonaro during a 2018 campaign rally. The primary purpose of that image was to promote a conspiracy theory that associates Lula with the attack.

Private but Also Public Groups

Message platforms are attractive for allowing users to easily create and organize chat groups, which are usually limited to hundreds or thousands of users, depending on the platform. Groups are private by default, and group managers invite others and decide who can join them. Group managers can invite other users to join the group by sharing with them the group URL (that is, “chat.whatsapp.com/group_id”) and anyone with access to the link can join the group. From a practical perspective, if a group manager or any user in the group shares the URL in public digital spaces, such as websites or social networks, the group becomes publicly accessible. This raises concerns about security and privacy, as individuals in these groups expose personally identifiable information (including phone numbers) to all the other users in the same group.7

Public groups usually work to connect users around specific themes. For example, one can join a public group to discuss specific games, get local tips on how to make craft beer at home, or share travel experiences. WhatsApp group features such as voice/video calling, polls, and emoji reactions improve the overall chat experience. Social networks are usually rich sources for finding public groups from WhatsApp, Telegram, and Discord. It is easy to find invitations for users to join public groups about a wide range of topics in different social networks, including potentially harmful topics and sex-related material.7 Increasingly, those platforms have been designated as places for sharing content containing revenge porn and deepfakes where individuals create fake nudes of teenage students and share them in school-related groups.3

In the 2018 Brazilian elections, public groups in WhatsApp were widely used by activists interested in supporting their political candidates to connect and organize social movements.15 While this is not necessarily a bad thing, these groups soon became suitable targets for misinformation campaigns, amplifying the reach of any kind of information that supports a candidate in a polarized campaign and working as a backbone for misinformation propagation.14 Later, in the 2022 Brazilian elections, nurtured by misinformation campaigns and conspiracy theories,6 WhatsApp and Telegram groups were radicalized and became places for organization of antidemocratic acts, resulting in the Brazilian version of the Capitol invasion.2

In summary, public groups are key for mobilizing political activism, but also a perfect environment for radicalization, as users in these groups tend to be targeted and orchestrated by misinformation campaigns. From the point of view of a misinformation campaign, public groups are the open doors to distribute content in message platforms and through which the misinformation campaign can be amplified and reach even private groups.

Viral Forwarding under Encryption

Conversations on message platforms such as WhatsApp and Telegram are end-to-end encrypted, meaning anything shared in a group is only seen by those involved in the discussion, providing users with a secure channel for communication. However, content shared in a conversation can be forwarded to other users and groups. Ultimately, a private conversation can become public if widely propagated.12 Moreover, when a message or content is forwarded in WhatsApp, the identity of the message creator is not forwarded along with the message. Therefore, it is nearly impossible to know who created viral content inside a platform such as WhatsApp, a relevant condition for a misinformation campaign to hide its tracks. Thus, on one hand, messaging apps guarantee user privacy and security through encryption of their data. On the other hand, the platform offers typical tools from social networks for easy and fast dissemination, facilitating content to get viral, occasionally obscuring the authenticity of content.

It is difficult to know to what extent these misinformation campaigns are affiliated with political parties or candidates, but it is reasonable to speculate they rely on a combined network strategy in which producers create misinformation and broadcast it to regional and local activists, who then spread the messages widely to public groups. From there, the messages travel even further among activists, also reaching the private part of WhatsApp.12 Usually, if misinformation goes viral in a social network, it can be at least debunked. But if it spreads within message platforms, there is no means to track its full reach or origin, and it is not even possible to assess if the content is getting viral. In other words, it is impossible for someone to identify and debunk misinformation shared within a group if he/she is not a member of the group. Thus, from the perspective of a misinformation campaign, false information shared in message platforms is harder to track, identify, and debunk compared to content shared in social networks.

Exposing Viral Content from Public Groups

During the 2018 Brazilian elections, WhatsApp became a battleground for a misinformation war, where orchestrated campaigns flooded the platform not only with popular fake news websites, but also manipulated photos,15 decontextualized videos,16 and audio hoaxes.11 Journalists were not able to debunk every piece of misinformation they encountered and were worried about exposing misinformation in a respected news outlet, boosting a conspiracy theory. During this time, there was a clear demand from members of the Brazilian press to assess what content was going viral in message platforms so they could fact-check for accuracy.

To help factcheckers and journalists, we developed a system to expose the most popular content (that is, video, audio, images, long texts, and URLs) shared in public groups associated with Brazilian politics.13 This system was widely used during the 2018 Brazilian elections by five fact-checking agencies, hundreds of journalists, civic society entities, governmental institutions, and non-profit organizations. For example, our system provided data for project Comprova,a gathering 24 Brazilian newsrooms to debunk misleading content. Lupa, a relevant fact-checking agency in Brazil, analyzed the 50 most-shared images from 350 groups we were monitoring over a period of three weeks before the elections. Nearly 92% of those images were fake or misleading.18 Our system provided material to dozens of news pieces in the main news outlets in Brazil and around the world,5 which helped everyone to better comprehend the misinformation phenomena in Brazil.

After the 2018 elections, misinformation campaigns continued to operate within message platforms to justify government decisions, undo crises, or simply to keep voters polarized and involved in political activism. We kept our monitoring system running from 2018–2023 as it was useful in many situations, including when universities were attacked by misinformation campaigns, during the fires in the Amazon Forest in 2019, and during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to the WhatsApp monitor, we built a system for the 2022 Brazilian presidential election to monitor Telegram public political groups,8 given the increasing popularity of Telegram in Brazil. This project has also established a partnership with Brazilian Superior Electoral Court (TSE),19 helping to expose misinformation campaigns that target the Brazilian electoral process.

Connecting Message Platforms with Fact-Checking

Unfortunately, fact-checking has little or no impact in public groups of political activists and radicalized users. Indeed, we noted that most of the messages circulating in our monitored groups were already debunked by popular fact-checking agencies by the time they were shared. Ideally, fact-checking could be much more effective in message platforms if those platforms were able to flag misinformation to users. Next, we discuss these ideas, detailed in Reis et al.14

The messages in systems like WhatsApp are encrypted in transit, but not in the end-point devices such as smartphones and computers. Thus, we propose a system design for message platforms in which they can flag content when it arrives in the user device or when the user is about to send it, without violating users’ privacy. In short, the idea is to maintain a set of hashes of images or other content that have been previously fact-checked, either from publicly available sources or through internal review processes. These hashes would be shipped with the message platform app, stored on a user’s phone, and periodically updated based on moderators or through a network of fact-checkers, such as the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN). Once a user intends to send an image, WhatsApp would check whether it already exists in the hashed set on the user’s device. If so, a warning label could be applied to the content or further sharing could be limited.

The strategy could be used to prevent coordinated misinformation campaigns near elections and other high-profile national and international events (such as the COVID-19 crisis). It could also be explored to counter other kinds of threats in the message platforms, such as child pornography or the exchange of fake nudes in group schools.

Reducing Virality within Message Platforms

During the most intense moments of the misinformation war in 2018, we authored an opinion letter18 proposing temporary modifications for WhatsApp to curb misinformation leading up to the election. The suggested changes aimed to restrict the virality features, including the number of users allowed to forward a message, and imposed limitations on groups for diminishing the impact of coordinated efforts by groups engaging in large-scale misinformation campaigns. Two days after our proposal, WhatsApp took action, suspending 100,000 accounts in Brazil. Additionally, two months later, the platform globally implemented limitations on message forwarding.

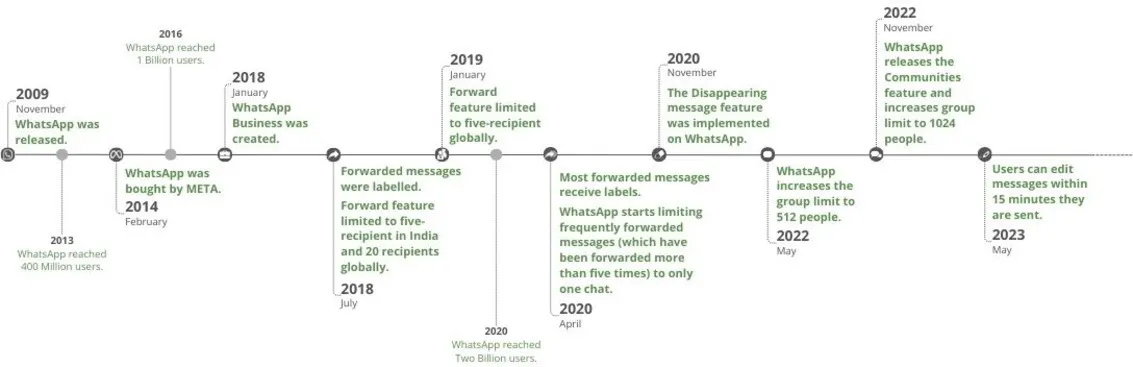

The evolution and misuse of public groups on the platform prompted modifications to WhatsApp’s architecture, illustrated in the timeline presented in Figure 3. Instances of mob lynchings and rumors in India in early 2018 triggered WhatsApp to enforce forwarding limits, restricting users to forwarding messages to a maximum of 20 contacts. The platform also introduced a “Forwarded” label to differentiate messages sent directly by users from those shared through forwarding. This labeling mechanism offers users a clearer distinction between personalized messages and the viral content circulating on the platform.

Throughout the 2018 Brazilian election, the influential role of WhatsApp in facilitating the widespread dissemination of viral content became more evident. The forwarding features proved effective in propagating content at scale within the network,12 ensuring its persistence across various platforms.16 In response, WhatsApp implemented a reduction in forwarding to a limit of five recipients. Recognizing its potential as a mass communication platform, WhatsApp implemented further self-regulatory measures, incorporating even more restrictive limits on simultaneous message forwarding in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. This involved introducing the concept of most forwarded messages and restricting them to only one share at a time.

Despite implementing several measures to restrict virality, competitors such as Telegram have gained popularity by accommodating groups with larger capacities with up to 200K users, and channels that empower administrators to broadcast messages to a vast audience. Recently, WhatsApp has also introduced features that amplify the potential for content to go viral on the platform. The group size limit has been expanded to 1,024 members, and the introduction of communities facilitates and accelerates the sharing of messages across multiple groups simultaneously.

Overall, the introduction of some features that restrict virality in response to the abuse of misinformation campaigns in the platform end up being just for the sake of appearances, as new features that increase the virality capability were later introduced. Associated with the lack of transparency from message platforms and ways of externally auditing these environments, they are very suitable places for misinformation campaigns to operate and they will continue to threaten the many different sectors of our society by offering a battlefield for an information war.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by research grants from CNPq, CAPES, FAPEMIG, and FAPESP.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment