There has been increasing concern about the availability of support for basic research in computer science.2 Although there are always factors such as budget priorities and federal funds availability, based on my experience as a program manager at the U.S. Defense Advanced Projects Research Agency (DARPA) I believe there is an additional factor that is often missed. Neal Lanea has spoken and written on related issues for science and technology in general; here, I focus on computer science.

The issue is the strength of the computer science representation “at the table” when priorities are decided and resource allocations are determined. The only way to change the resources allocated to computer science as a discipline is to ensure the best new ideas are represented passionately, effectively, and repeatedly. This means going beyond the advocacy role of representative organizations such as the Computing Research Association and voluntarily becoming public servants: to become agents for change.

What Can You Do?

Federal agencies such as DARPA and the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) are constantly looking for new ideas and people to make them happen. Making ideas happen is the role of public servants such as DARPA program managers and NSF program directors, and these ideas are often far beyond what the risk/reward threshold of the private sector can support.

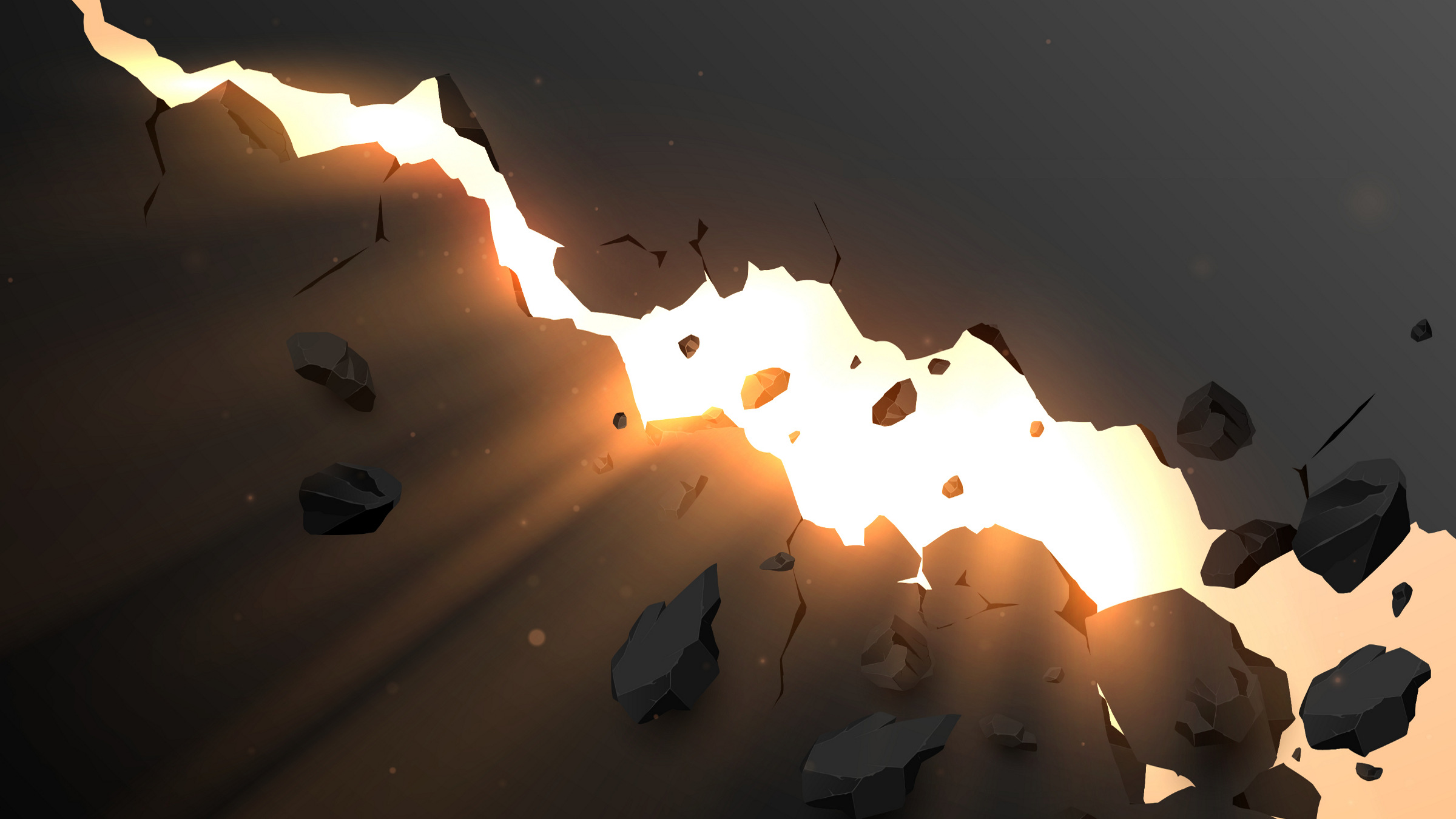

The figure here depicts a conceptual model of the effect that good program management can have on research risk and reward. The line labeled “Risk/Reward Curve” is meant to suggest there is a natural relationship between risk and reward, where low risk leads to low rewards and high risk is required to achieve the highest rewards. It is the goal of program management to create an environment in which the most rewarding research is pursued with the least risk. The rewards are typically clear in the program manager’s vision, so it is risk that must be managed most aggressively.

Risks to manage include problem difficulty, researchers, time, and money. To manage problem difficulty, intermediate goals can be targeted, or multiple competitive approaches can be supported to reduce risk through a process akin to “portfolio management.” Researchers must be encouraged to be bold, but at the same time to be objective in deciding whether an approach may not be yielding results. Time and money are closely related and difficult to manage because breakthroughs are impossible to schedule, but competition for resources brings the estimates of other experts to bear on the questions of what results can be expected, how long it will take, and how much it will cost.

Therefore, in addition to vision and new ideas, effective program managers will bring deep expertise and credibility in their scientific discipline to their role in government. Depth is necessary to understand the real risks in a problem domain, to select the most promising researchers and plans, and to distinguish true technical innovation from rhetorical skill. Deep expertise and credibility require that program managers be drawn from the scientific community, while public service entails standing somewhat apart from the community, for fairness and to prevent real or perceived conflicts of interest. The perspective of a public servant drawn from the scientific community can be both challenging (since it requires a view at “field” level or even “national” level, rather than “specialty” level), and a tremendous opportunity for community and personal growth.

What Do You Get Out Of It?

One unfortunate, destructive, and derogatory myth about program management is that it is a purely administrative job, giving management briefings, rating proposals, and dunning people for annual reports. It is not. There are huge technical, professional, and personal rewards.

On the technical front, you are exposed to real problems, new technologies, and alternative solutions that you might never have imagined without the experience. A sample suggestion I got when I was looking for applications for my approaches to extreme networking environments was “read Black Hawk Down,” which focused my attention on wireless communications and the problem-rich urban communications environment, leading to, for example, efforts in cognitive networking (SAPIENT, for Situation-Aware Protocols in Edge Network Technologies4) and distributed radio (ACERT, for Adaptive Cognition-Enhanced Radio Teams1,5). The broad exposure to other problems (for example, the traditional sciences, engineering disciplines such as aerospace, and emerging areas such as programmable matter) allows you to inject computer science thinking where it is necessary and shape new opportunities for advanced research.

The perspective of a public servant drawn from the scientific community can be both challenging and a tremendous opportunity for community and personal growth.

The professional rewards accrue from doing a great job in public—you are never more visible than when you are in Washington, D.C., and your impact may persist for many years as a result of the programs you create and the people and teams you support. It is no surprise that your peers take notice and give credit where it is due. Further, the new skills you have gained catapult you into a new realm of mentoring and advisory roles, since they have direct bearing on the ability of any group to accomplish an agenda.

On the personal front, your service is the chance to set an agenda based on your new ideas, and support intellectual leadership for this agenda with significant resources. As an example, program managers at DARPA are hired based on their vision for change. Subtle changes can have surprising impact, for example, encouraging open source deliverables to stimulate software radio research.1,5 As an added benefit, you have access to a new form of publication, the research solicitation, which will be read far more closely by proposers from your community than any conference or archival writing you do before or after your service. The solicitation itself can serve as an important tool in sparking new ways to approach problems.

Do You Have to Give Up Your Job?

Opportunities exist for academic researchers to perform public service while retaining their institutional affiliations, which of course demands extra care to avoid conflicts of interest. This can be accomplished, for example, under the Intergovernmental Personnel Act, which allows an agency to “borrow” staff members from the academic institution. Conflicts of interest, for example, would arise when the home institution is involved in a solicitation, and you must remove yourself from the decision-making path. Scholarly activities such as mentoring students that are near graduation can continue, albeit on a voluntary rather than a compensated basis.

Conclusion

Research really is an endless frontier,3 and the impact of our “general-purpose machines” on life and society has only just begun. I encourage you to consider public service as a way to keep the frontier spirit alive in the computer science community.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment