Technology has improved bicycles for serious and casual riders, enabling features that make some fly, others shrug. Social and mobile connectivity trends and communications tech are being tapped to deliver extras not available a few years ago.

The cycling computer is a case in point. Ten years ago, most models were based on a 100-year-old design that used frame-mounted magnets to count wheel rotations. A wire led to the tinny device with a tiny display on a bike’s handle bars that showed speed, distance, and related metrics. It was a bike version of a pedometer; “computer” seemed an overstatement. That’s a long ride from cycling computers and smartphones with GPS receivers and apps common to today’s riders. Add fitness trackers, smart watches, and wireless connectivity to the mix. Singly or in combination, they deliver maps that show where you’re going, where you’ve been, break a trip into pieces called “segments,” track miles, heartrate, incline, average speed, calories burned, and more per segment and total ride, compare that to yesterday’s performance, to other riders’ performance, to your PR (personal record; time to get one?), and lets other riders track you as well. “He’s done 11,000 miles this year,” said one rider, smartphone in hand, comparing his miles to a rider he follows on Strava, a popular fitness app. “He’s retired. Lives in Florida half the year.” About another: “Ride with him.” Another: “Saw him this morning.” Strava provides real-time or post-ride data, goals, and—like other fitness trackers—positive reinforcement or merciless self-assessment: “Only 4,300 miles this year,” the rider said in August. “Old and fat.”

Some riders don’t care for apps, maps, or performance metrics. “Don’t use them,” said Marcello, a rider in New York City. “I know my way around.” His smartphone (“always with me”) serves another role. “Always listening to a podcast,” he said.

Apps also enable accessories. An Apple Watch app and a gesture from the rider light up the yellow LEDs on the back of the Lumos Kickstart Helmet to indicate the direction of a turn. The LEDs can also be activated by a Bluetooth, two-button (left/right) remote on the handle bars. “Drivers can see your intentions and give you space,” says Eu-wen Ding, founder and CEO of Lumos Helmet. An accelerometer in the helmet detects when the bike is slowing down, triggering red LEDs on the back, helping a rider “be seen and be safe,” Ding says. The helmet also connects to the Strava app to record activity automatically. The Kickstart helmet is available from Apple Stores and elsewhere. One Apple Watch fanboy was so enamored of the helmet that he considered taking up biking, said an employee at an Apple Store in New Jersey.

Smartphone apps underlie bike-sharing services in scores of major cities. The app for Citi Bike in New York tells riders where they can find one of the system’s 12,000 bikes, unlocks it, handles the rental transaction, and says which of 750 docking stations have room for a return. Using Citi Bike data, programmer and blogger Todd W. Schneider graphed 47,969 trips taken in a single day.

Citi Bikes “crush taxis” on certain days and routes, Schneider says. They also pass New Yorkers’ ultimate UX test: Do tourists get it? “It’s really easy,” said Christina, from Spain, docking a Citi Bike in Chelsea. “I just came from Central Park.”

Pedal-assisted electric bikes, or e-bikes, are mainstays of other bike-share services like Lime and Jump. E-bikes blur the lines between pedal bikes and motorcycles. Advances in programming, reliability, and battery capacity have raised e-bikes’ appeal to baby boomers, says Chris Nolte of e-bike retailer Propel Bikes in Brooklyn. A 32-bit processor electronically controls the maintenance-free Bosch motor on Riese & Müller (R&M) e-bikes, and monitors 1,000 sensor measurements per second for power, pedal rate, and speed. The handle throttle is a thing of the past. “A strain gauge checks how hard you’re peddling and the motor delivers power in proportion to that,” Nolte says. “It ends up feeling you’re stronger than you are, as opposed to you’re getting an assist. You have to work. You’re getting exercise.” Dual lithium-ion batteries provide up to 1,000 watt-hours of power, twice as much as older e-bikes. Commuters can arrive at work without being drenched in sweat. Child seats, tandem models, and cargo boxes raise the boomer appeal. Nolte rides a classic racer, and his wife keeps pace with an e-bike. The max speed of an R&M e-bike with pedal-assist runs up to 20 mph. More powerful motors are available, but 20 mph is the speed ceiling for e-bikes in New York City and elsewhere; any faster, and it’s a motorized vehicle, like a motorcycle.

While e-bikes also appeal to older, less-fit, or Sunday riders, the purist notion of the e-bike is changing. “Sometimes the argument is ‘this is cheating,’ but that controversy is dying down,” Nolte says. “As the technology improves, there’s a certain respect for it.”

Pedal-assist is a boon to haggard deliverypeople. Eighty percent of New York City’s 50,000 mostly immigrant delivery workers use e-bikes, according to the city’s Department of Transportation. They are a common sight at lunchtime on NYC’s major avenues. “More easy, less peddle,” said Gustavo, happy with his four-month-old e-bike. “More hours, no stop,” he said.

Technology and apps are changing stationary bikes as well. Apps and options mimic some social aspects of a spin class or group ride without the social pressure. Quit in the middle of a session? Not cool at a fitness studio, AOK when home alone. The aim is for an immersive experience. The Schwinn Classic Cruiser from Nautilus Inc. includes a workout option where a rider can pedal through a virtual 1950s town delivering newspapers and earn extra points for dinking a gnome (or lose points for breaking a window). The bike’s a beaut, with a retro look and candy-apple-red paint job, yet it’s more than just another pretty face: “It’s a serious piece of exercise equipment,” a Schwinn spokesman says. The Classic Cruiser app tracks time, distance, calories burned, and other stats. Rather than an adjustable knob, the bike shifts through seven levels of resistance electronically. An advanced electromagnetic flywheel delivers a whisper-quiet ride, the spokesman says. With a 3-sq.-ft. footprint, it suits “a parent or grandparent,” or a space-constrained city-dweller on days pleasant, pouring, or broiling. It’s compatible with Zwift and RideSocial, fitness apps with social elements and virtual routes. Connect it to a big-screen HDTV and a user can ride and communicate with others while moving through Australia, the Swiss Alps, and other virtual environments. The Classic Cruiser has a casualness that doesn’t square with go-go fitness apps, which “makes every workout a more fun and enjoyable experience,” the spokesman says.

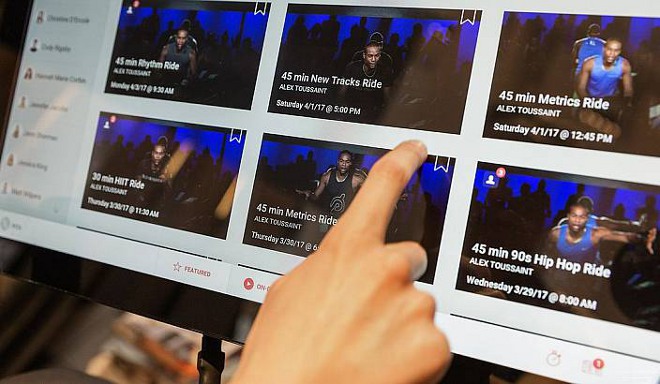

Peloton is a leader of the pack in bike tech. The $1,995 stationary bike (plus $39/month subscription fee) provides a virtual spin class with potentially hundreds of other riders. Thirty-, 45-, or 60-minute classes, pre-recorded or live from a studio in New York, are available every day. The company syncs all those riders with a timing signal inserted into the data layer of MPEG video delivered to the bike’s 22-inch 1,080p HD touchscreen. The on-screen instructor can give a shout-out for reinforcement or hitting a personal milestone. The company invested in a distributed storage solution, hosted on AWS, that supports a real-time leaderboard that can handle thousands of concurrent riders. The leaderboard is replayed for pre-recorded classes. “There’s a lot of custom logic to minimize latency and maximize data throughput,” says Yony Feng, Peloton co-founder and chief technology officer. An internal team designed the bike’s hardware and software, and a chipmaker collaborated on the console’s chipset.

difficulty, music, or instructor.

Virtual classes and engaging instructors help remove the drudgery from those last five miles till home. Yet there’s a difference; a road rider has to finish the miles, while only 36% of Peloton’s customers complete their workouts, CNBC said.

David Roman is Web Editor for CACM.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment