In these days when so much of life seems to take place on a Web site or over a smartphone, health care is still remarkably lacking when it comes to information technology. Of course billing is done mostly by computer, and in the past few years the electronic writing of prescriptions has soared. But most medical records are still on paper, and even those in digital form are not easily shared between doctors or readily accessible to patients. Data that could aid in understanding a patient—activity patterns or dietary habits—aren’t captured. Patterns that might indicate a problem with a drug or suggest a better method of treatment aren’t noticed.

A special commission, the U.S. President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST), issued a report last December calling for the creation of an information technology infrastructure for health care in the U.S. Such an IT ecosystem starts with the widespread adoption of electronic health records. But it could go beyond that to devices that collect data about how people live their lives or offer them feedback for making healthy choices. It could include individual databases that gather information relevant to health from a wide variety of sources, and collections of aggregated, anonymized data to aid public-health decisions or supplement clinical trials.

Converting health records to electronic form is a major federal goal. The stimulus package of 2009 provides at least $20 billion over the next five years to promote the adoption of electronic health records, with doctors and hospitals qualifying for extra Medicare and Medicaid payments if they make “meaningful use” of such records. The PCAST report found that nearly 80% of doctors lack even rudimentary digital records. “Of those who do use electronic systems, most do not make full use of their potential functionality,” the report states. “The sharing of health information electronically remains the exception rather than the rule.”

The report recommends that the government promote a universal exchange language for health-care data, based on metadata-tagged elements. Done right, that would allow large organizations to keep their current systems but share data with others that are now incompatible. It would also let innovators create new programs that could run on top of those systems, as well as new mobile apps for consumers that could feed data into a personal health record.

Shareable, accessible digital records could improve the quality of care in a number of ways. If a patient from Boston, for instance, is rushed to an emergency room in Seattle, doctors could immediately find out her allergies, what medications she’s on, or a recent surgery that might be contributing to her medical condition. A computer might alert a doctor to potential drug interactions, or send a reminder to follow-up on a lab test. Gordon Schiff, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and a doctor at Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital, envisions something like a wiki, “where you sort of continuously evolve a description of a patient. You don’t have to start from scratch every time.”

Such a system has the potential to reduce diagnostic errors, argues Schiff, by providing a more thorough patient history, highlighting potential problems, and making it easier for doctors to share their diagnostic thinking. Although he doesn’t think it will happen soon, someday computers may even guide doctors toward a diagnosis. Schiff has invited the creators of IBM’s Watson, the machine that beat a duo of Jeopardy champions earlier this year, to address that possibility at the Diagnostic Error in Medicine conference he’s co-chairing in October.

But health information need not be limited to doctor’s visits and lab tests. A second PCAST report, “Designing a Digital Future,” focusing on networking and information technology, was released a week after the health IT report. It envisions a more comprehensive, lifelong record that includes not only treatment history but also a genetic profile, psychological characteristics, behavior patterns, and exposures to risks that might be relevant to health. While such a record could benefit individual patients, it could provide even greater value when stripped of personally identifying information, combined with similar records, and subjected to data mining algorithms.

It would, for instance, create a sort of extended clinical trial for approved drugs, says Susan Graham, a computer science professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and a member of the report’s working group. Today’s drug trials stop with the approval of a medication, “yet while people are taking these drugs there’s an accumulation of experience about what the side effects are and what the potential benefits are,” Graham says. The healthcare group Kaiser Permanente has already demonstrated such a benefit; electronic records for its 8.6 million members helped identify the link between the painkiller Vioxx and an increased risk of heart attacks.

With an entire nation’s health records at their disposal, computers might also find early warnings of epidemics or identify which treatment approaches work best.

With an entire nation’s health records at their disposal, computers might also find early warnings of epidemics or identify which treatment approaches work best. Graham points out that only major diseases that affect millions of people tend to be studied. A huge database could provide valuable insights into less common disorders. “It’s only possible if all of the information on which that kind of insight is based is, number one, electronic, and number two, available,” she says.

At-Home Monitoring

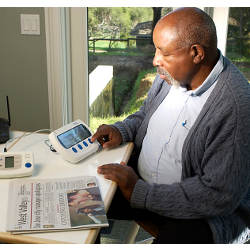

Health records could also be fed by devices that collect information about people as they go about their lives. The U.S. Veterans Administration (VA) system already uses the Health Buddy, an electronic device that plugs into a home phone line or Ethernet socket. Each day patients answer a series of questions tailored to their particular medical conditions, asking, for example, whether they have taken their medications or about their glucose levels. Answers are sent to the VA and flagged if they show warning signs.

“Versions of that will be in every home, or at least every home where there’s a health condition that could be supported by that,” says Molly Joel Coye, head of the UCLA Innovates Healthcare initiative at the University of California, Los Angeles. “We will know what your blood pressure is every morning at 8 o’clock, or how it varies during the day, instead of every six or eight months when you go to the doctor.”

Such increased monitoring could catch potential problems earlier, perhaps leading to more effective treatment or outright prevention of some conditions. It could also reduce costs. The VA estimates its in-home monitoring saves thousands of dollars per patient by reducing doctors’ visits and nursing home care.

The growth of the “Internet of Things,” in which now-discrete devices are networked, could provide both monitoring and feedback, suggests Isaac Kohane, professor of pediatrics and of health sciences and technology at Harvard Medical School and director of informatics at Boston’s Children’s Hospital. Your refrigerator, for instance, might offer suggestions to help you adhere to your diet, or the motion sensor in a gaming system could be used to guide physical therapy. “Pretty much everything we’re doing today could have a sensor,” Kohane says. “Your scale could have an IP address.”

With electronic patient-monitoring devices, “we will know what your blood pressure is every morning at 8 o’clock, or how it varies during the day, instead of every six or eight months when you go to the doctor,” notes Molly Joel Coye.

There’s already a package of sensors that many people carry around with them every day: their smartphone. “People are walking around with devices that make it much easier to capture in-the-moment data,” says Deborah Estrin, director of the Center for Embedded Network Sensing at UCLA. Analyzing patterns of a smartphone’s GPS traces could reveal changes in a person’s behavior, perhaps signaling, for example, a bout of depression or an increased risk of suicide.

Estrin is a proponent of developing an open architecture for mHealth, the practice of using mobile communication devices for monitoring patient health. A patient telling a cellphone app about symptoms or pain levels will be more accurate about how he’s feeling right now than trying to recall these details in a visit to the clinic days or weeks later, she says. Existing apps already help people keep track of diet and exercise, for instance, but if they could feed the information back into a permanent health record available to the doctor, they could offer much greater benefit.

Protecting Patient Privacy

If all this is to work, strong privacy protections will be important. Latanya Sweeney, professor of computer science at Carnegie Mellon University, says data should be segmented and in the control of the patient. This way, a patient could share information about an HIV test only with her primary-care doctor while letting everybody know about her allergies. There also should be a way to track who sees patient data to help prevent abuse, Sweeney says. If a bank, for instance, is buying information about a customer’s cancer risk and using it to adjust their credit scores, a patient ought to know. Sweeney worries that a lack of privacy incentives in the health-care initiative will produce a backlash.

Even with patient names stripped away, it’s possible to cross-correlate data and expose private information, the way some researchers have used public data to deduce an individual’s Social Security number. On the other hand, Graham points out, preventing all such correlations could mean missing connections and patterns that might improve patients’ health. Reaching the right level of data protection, Graham says, is both a technical challenge and a policy issue.

Sweeney sees a lot of value in developing an IT ecosystem, but is skeptical about how quickly it will develop. “For me, the excitement is in the sharing level, but we’re not there,” she says. “We’re not apt to get there in 2015.”

Computer scientists will have to work with doctors to figure out what is technically feasible and how IT can fit into the practice of medicine, says Graham. The capture of information in clinical settings has to fit into the workflow, so providers don’t find it burdensome. And they will have to guide the policy makers who will make the regulatory and financial decisions.

“It really needs to be interdisciplinary,” Graham says. “This is not just a computer science topic.”

Coye, M.J., Haselkorn, A, and DeMello, S.

Remote patient management: Technology-enabled innovation and evolving business models for chronic disease care, Health Affairs 28, 1, Jan.Feb. 2009.

Graham S., Estrin D., Horvitz, E., Kohane, I, Mynatt, E., and Sim, I.

Information technology research challenges for healthcare: From discovery to delivery, Computing Community Consortium, May 25, 2010.

PCAST

Realizing the Full Potential of Health Information Technology to Improve Healthcare for Americans: The Path Forward, The White House, Office of Science and Technology Policy, Dec. 8, 2010.

PCAST

Designing a Digital Future: Federally Funded Research and Development in Networking and Information Technology, The White House, Office of Science and Technology Policy, Dec. 16, 2010.

Schiff, G.D. and Bates, D.W.

Can electronic clinical documentation help prevent diagnostic errors? New England Journal of Medicine 362, 12, March 25, 2010.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment