Consideration of Artificial Intelligence is integral to most discussions of robotics. One educator is changing the conversation by asking instead, "What about artificial creativity?"

Gil Weinberg, founding director of the Center for Music Technology at the Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech), is looking to the future of robotics by exploring artificial creativity; specifically, creative robots and how humans can be inspired to create something new.

Weinberg expressed the foundations of his research in a 2007 paper, "Robotic Musicianship – Musical Interactions between Humans and Machines." In 2011, He gave a TEDx talk on Robotic Musicianship, in which he spoke about leveraging technology to expand musical expression and creativity, and about robots as musicians.

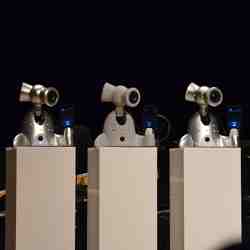

He recently demonstrated developments in robotic musicianship at Kennesaw State University in Kennesaw, GA, as part of the Atlanta Science Festival, showing off robots such as Haile, a percussionist that can improvise and play along with other drummers; and Shimon, a four-armed robot that plays the marimba, covering jazz masters like John Coltrane and Thelonious Monk as well as improvising with human musicians.

Weinberg defined artificial creativity as "using artificial intelligence to produce a creative outcome that was not programmed directly as part of a deterministic algorithm." He said he sees some level of creativity within robots like the Roomba robotic vacuum cleaner, which "goes around your house and you do not always know where it will go next. Maybe we can consider this, too, as a form of robotic creativity and improvisation."

He said he has tried to take the idea of artificial creativity "and push it towards music and artistic creativity—forms of expression that only us humans have. I am trying to explore whether humans can be inspired by what the robots come up with. Can [creative robotic musicians] expand the way we think about music and art?"

Weinberg focused on creative robotics in the context of music, rather than exploring robotic development in more practical fields such as medicine, because "I was a musician first, and in college I got into computer science." He studied computer science at Tel Aviv University in his home country of Israel before coming to Georgia Tech, where he first started thinking about artificial creativity as he helped develop software that would create new music.

‘The original reason was that I became tired of digital music’s sound. I worked for years on developing software that listened to, analyzed, and improvised music using digital sound processing. I wanted to continue to work on such algorithms, but to get a rich, acoustic outcome instead of stale speaker sound." That’s why he started thinking about creating a "musical brain that can create interesting musical interactions, but also have rich acoustic sounds and visual cues."

The "visual cues" to which Weinberg referred are the "instinctive cues" and physical changes musicians make as they play. Musicians that play together constantly watch the each other for these changes, in order to maintain harmony and rhythm.

Weinberg and his team built robots that could play music and interact with humans in very human-like ways. They created the four-armed Shimon robot with a blinking "eye" to make it obvious to other musicians whether the robot was nodding to the beat or looking at them as it played along with them on the marimba.

For the Shimi robot, which plays music with an iPhone charging dock, "We added cameras to provide another level of intelligence: visual intelligence," Weinberg said. "Shimi can analyze the way you dance, chose a song in a particular tempo from a particular genre based on your dancing style, and then dance with you using appropriate gestures."

Weinberg’s latest development is an offshoot of his research on artificial creativity in music. He was contacted by Atlanta Institute of Music and Media student Jason Barnes, who had lost his right arm in a work-related accident, in the hope Weinberg could develop a prosthetic that would allow Barnes to play the drums again. Weinberg created for Barnes a prosthetic hand equipped with two mechanized drumsticks: one allows Barnes to control the sound of each hit through the selection of different grip techniques; the other analyzes what Barnes plays with his left hand, then improvises based on that. The two drumsticks also can be synched together to do a drumroll that is "faster than what any human can do," according to Weinberg.

Ultimately, Weinberg told CACM, "I think (a push for creative robots) is starting. Robotic creativity does not have to apply to just art and music. There will be other robot developers that will be trying to create creative robots. I anticipate this will be one of the next waves in robotics."

Daniel Lumpkin is News Editor for The Sentinel, the Kennesaw State University student newspaper.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment