Europe’s contribution to computer science, going back more than 70 years with Alan Turing and Konrad Zuse, is extensive and prestigious; but the European CS community is far from having achieved the same strength and unity as its U.S. counterpart. Last October, a European Computer Science Summit was called to bring together—for the first time—CS department heads throughout Europe and its periphery. This landmark event was a joint undertaking of the CS departments of the two branches of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology: EPFL (Lausanne) and ETH (Zurich).

The initiative attracted interest far beyond its original scope. Close to 100 people attended the summit representing most countries of the European Union, along with Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine, Russia, and Israel. A delegate from South Africa also participated in the event as did a U.S. representative of the ACM, Russ Shackelford. The program consisted of two keynotes and a number of panels and workshops on such themes as research policy, curriculum harmonization, attracting students, teaching CS to non-CS students, existing national initiatives, and plans to create a Europe-wide organization.

A major reason the summit attracted such immediate and widespread interest is that CS in Europe faces a unique set of challenges as well as opportunities. The challenges discussed at the meeting include some old and new themes. The fragmentation of Europe and its much treasured cultural diversity have their counterparts in the organization of the educational and research systems. To take just three examples from the education side, the U.K. has a system that in many ways resembles the U.S. standard, although with significant differences (three- rather than four-year bachelor’s degree, and different hierarchy of academic personnel with fewer professors and more lecturers); German universities have relied on a long (nine-semester) first degree, the "Diplom;" and France has a dual system of "Grandes Écoles" engineering schools, some very prestigious and highly competitive, but stopping at a master’s-level engineering degree, and universities with yet another sequence of degrees including a doctorate.

To harmonize these systems, the ministers of education of European countries adopted the "Bologna declaration" in 1999 defining standard study cycles—bachelor’s, master’s, Ph.D.—with the goal of facilitating mutual recognition of degrees, enforcing a common way of counting credits, and promoting such goals as student mobility (which was already on the rise thanks to quality control and such programs as Erasmus).

How to implement the Bologna process remains a major worry for many CS departments in continental Europe. One of the benefits of the summit has been to illustrate that it is not necessarily a life-threatening issue, rather an opportunity to improve and strengthen the curriculum while attaching internationally recognized labels (bachelor, master) to specific steps. This was confirmed by talks about the experience at ETH Zurich and Utrecht, as well as confirmation from French Grandes Écoles (Polytechnique, ENS Lyon, Ensimag Grenoble) that their programs are or would soon be Bologna-compliant. Utrecht’s Jan Van Leeuwen, whose department completed the process in 2001, insisted that such a significant educational change should be carried out quickly rather than dragged out over several years.

Independent of the Bologna process, and like most other places in the world, European CS departments have recently faced declining student numbers. The field’s negative image (especially among women), the burst of the Internet bubble, and the fear of outsourcing have all contributed to this broad decline. A few well-publicized rumors have somehow led many people to believe there is high unemployment in the computing field—while, in fact, recent statistics at ETH show that CS graduates have the second-highest hiring rates of all disciplines.

To a certain extent we are experiencing the downside of the hype phenomenon after being on the upside just a few years ago, but in some cases this borders on the absurd. For example, a recent string of articles in the popular press in Switzerland drew from a handful of unrelated police cases and gravely asked whether the proportion of murderers is higher among computer programmers! Such cases are laughable, but characteristic of a general problem with popular perceptions. Participants expressed the strong desire to work collectively to develop a more upbeat image of the CS field. Contrary to popular opinion, most computer scientists have excellent job prospects in most European countries.

European research policy also presents significant challenges. The Esprit initiative and the various frameworks that have followed it have changed the European landscape for technology research, forcing a transnational shakeup of teams and ideas and introducing many opportunities for university-industry cooperation. But there is also a general feeling of bureaucratic heaviness, with the emphasis on consortium-style endeavors involving many partners from many nations at the detriment of smaller, more focused projects. Another characteristic of the European research scene in several countries is the important role of state research organizations not affiliated with universities; a similar situation exists in the U.S. for the health sciences, but not for the CS field.

The financial context raises interesting problems. With the exception of the U.K., Europeans generally want teaching to be free, save for modest administrative fees. In addition, there are neither major endowments nor a tradition of alumni contributions. The result is that European universities are generally far less wealthy than their U.S. counterparts, although the situation varies widely (Switzerland, for example, is very generous to its two technical universities). While some attempts are under way to increase student fees (for example, in Germany and Switzerland), the costs are unlikely to soon reach the levels common in the U.S. or Australia. Private universities in Europe are not common, which means any ambitious research effort requires funding from the state, either at the national level or increasingly from the European Union.

Certainly the CS picture is not all problems and obstacles. A constant theme at the summit, and the reason for its spirited sessions, was a realization of the opportunities open to CS in Europe. The near-gratuity of universities, along with its negative effect on funding, yields a more democratic access to education, and means that European universities have not turned into the fundraising-obsessed business machines their U.S. counterparts sometimes seem to be. The long cultural and scientific tradition of Europe is also a plus; studying on the same benches as Newton, Cauchy, Gauss, or Einstein is not a bad way to motivate oneself.

In the global competition for excellent Ph.D. students, a major advantage for the universities of some countries—in particular the German-speaking world, Northern Europe, and Switzerland—is the system of "assistants," or paid university employees who participate in teaching and the general life of their chairs while pursuing a Ph.D. This system is not without its drawbacks; for example, assistants are in danger of settling down into a content job, which is often not the best incentive to make a great Ph.D. But the assistant scheme is generally a great tool for attracting talent, especially in universities with comfortable salaries. For some Ph.D. candidates, the alternative is to go to a U.S. or Australian university where they must pay hefty fees.

Both U.S. citizens and Europeans who have spent time in the U.S. bring a much-needed North American academic research culture to blend with European traditions.

Several participants viewed the current U.S. political climate as offering a great opportunity for ambitious and competitive European universities and research centers. The tightening of visa procedures is turning away many potentially excellent candidates at the graduate-student level. The freezing of research funding outside of health care and homeland security (where the focus is on short-term applied work rather than research topics such as cyber security) has made the U.S. less attractive to senior researchers. European schools and others are benefiting from this situation by attracting top talent. In fact, both U.S. citizens and Europeans who have spent time in the U.S. bring a much-needed North American academic research culture to blend with European traditions.

It is clear, however, that this opportunity will not come to fruition without fundamental changes in the way European universities function. Better career opportunities for junior professors and more broadly based graduate education are among the key priorities. The current U.S. situation will not last forever, leading to a strong sense of opportunities to be seized now.

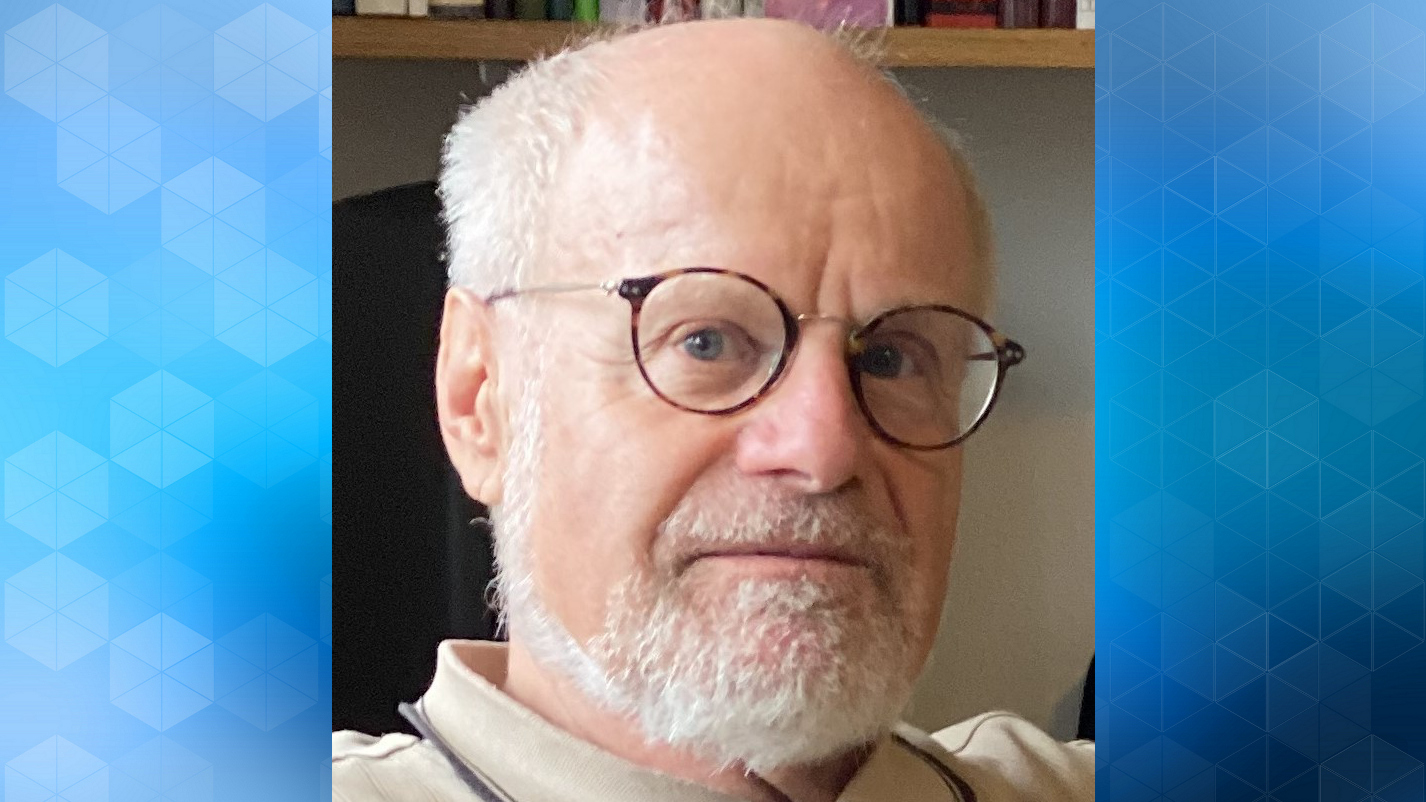

The avowed model for our meeting was the U.S.-based Snowbird conferences, which have served as a forum for North American CS department chairs for decades and resulted in the creation of the Computing Research Association. The CRA has had a profound effect on shaping the North American CS community and influencing public policy. Ed Lazowska, a CS professor from the University of Washington and chair of the CRA for many years, showed how much Europe can learn from this experience in his keynote address. Lazowska’s talk was a goldmine of information on the CRA story and on the CS community in North America, filled with facts, trends, and relevant statistics. It was an opportunity to appreciate how much we have to accomplish, starting with the first steps of gathering the basic data. Lazowska stressed that one of the first and most important tasks of the CRA has been to establish and maintain a proper list of departments and contacts. Indeed, we had a similar scenario in preparing the groundwork for the summit. The major challenge turned out to be reaching the relevant CS departments. There was no mailing list available, so we resorted to all possible means, from Web searches to postings on widely read mailing lists such as ecoop.org. It is no accident that the largest contingent at the summit came from countries where either a national organization or at least a mailing list already existed, through which we could reach interested people.

Another concern experienced by some universities is the evaluation of publications and more generally of research. Increasingly, professors and researchers are asked to have their publications, their citations, or both counted. At the same time, there is growing noise about performance-based resources and even pay—with performance measured largely by these counts. Regardless of one’s basic opinion of the wisdom of such counting exercises, it is clear that computer scientists in Europe have failed to make the specificity of CS with respect to publications generally understood and accepted. The risk still exists of being evaluated according to criteria poorly adapted to most of the CS discipline, such as the number of publications in Science or Nature. A first step toward assessing publication activity is to know exactly what to count and the methodological limit of what we can count.

Keynoter Michael Ley, who maintains the DBLP server in Trier (Germany), has a unique perspective on the topic. The DBLP lists CS publications, not citations, and results from an exacting effort to get the data correct through a combination of automatic and manual work. Ley described the difficulties raised by authors whose names appear in different formats (Michael Smith, Mike Smith, M. Smith), and by several authors sharing the same name (to which he applies coauthor analysis algorithms to help sort them), Asian names, and many other issues. He amusingly illustrated the perils of automatic analysis of documents by showing how a well-known citation database attributes articles on computer-aided design to a prolific researcher called "Johan Wolfgang Goethe" (The explanation: articles where the cover page lists John Author1, Jill Author2, Johan Wolfgang Goethe Universität where the last part is simply the authors’ affiliation, the Frankfurt university named after the great German poet.) Ley’s work is a model of rigor, care, and openness, which one may only wish were followed by all those in charge of counting who publishes what and who cites whom.

Another discussion at the summit was the role of women in CS, and how to draw and retain more of them into the field. Violaine Prince from Montpellier pointed out that women are generalists rather than specialists and that curricula should be adapted accordingly. On the topic of how to attract more students, an interesting example was provided by a few universities whose enrollment has actually been growing, thanks to new programs covering topics such as media informatics. Contrary to possible fears, these are not "soft" programs, but strong CS curricula that simply include a few popular themes, attracting an audience that might otherwise be put off by the (unintended) "nerdy" look and feel of the more traditional programs.

The most important result of the summit was the unanimous view that European computer scientists urgently need an organization with aims and scope similar to those of the CRA, extended—in light of the peculiar situation in Europe—to cover education as well as research. An initiative to start this organization is under way, and should culminate in an official start at the next summit tentatively scheduled for next September in Lyon. Some of the immediate tasks are:

- Starting the ground work: list of institutions, mailing list, and Web site.

- Defining criteria for publication and research evaluation.

- Defining guidelines for CS curricula.

- Proposing strategic directions for CS research in Europe.

- Attracting students to the discipline.

The aim of the association will be to become the recognized voice of the European CS community, not limited to universities, but including research centers and industrial research labs. The momentum created by this inaugural summit should enable us to take the first steps more quickly toward this goal by building on the enormous amount of goodwill and community spirit so apparent during the two days shared by 100 CS department chairs at a foundational event in Zurich.

For more information on the summit, visit se.inf.ethz.ch/ events/cs_summit_2005.

Join the Discussion (0)

Become a Member or Sign In to Post a Comment