Technical Perspective: Schema Mappings: Rules For Mixing Data

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

The Rise of the External Brain

Technical Perspective: Design Tools For the Rest of Us

Designing Plush Toys With a Computer

Maximizing Power Efficiency with Asymmetric Multicore Systems

Quantifying the Benefits of Investing in Information Security

Computing Journals and Their Emerging Roles in Knowledge Exchange

Steering Self-Learning Distance Algorithms

Internet Addiction: It’s Spreading, but Is It Real?

Deep Data Dives Discover Natural Laws

Student Research Competition at Grace Hopper

The Netflix Prize, Computer Science Outreach, and Japanese Mobile Phones

Unifying Biological Image Formats with HDF5

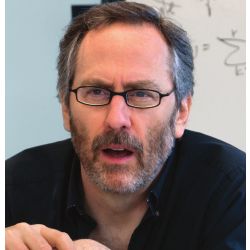

A Conversation with David E. Shaw

Probing Biomolecular Machines with Graphics Processors

Automated Support For Managing Feature Requests in Open Forums

Balancing Four Factors in System Development Projects

How Effective Is Google’s Translation Service in Search?

Shape the Future of Computing

ACM encourages its members to take a direct hand in shaping the future of the association. There are more ways than ever to get involved.

Get InvolvedCommunications of the ACM (CACM) is now a fully Open Access publication.

By opening CACM to the world, we hope to increase engagement among the broader computer science community and encourage non-members to discover the rich resources ACM has to offer.

Learn More